Commentary

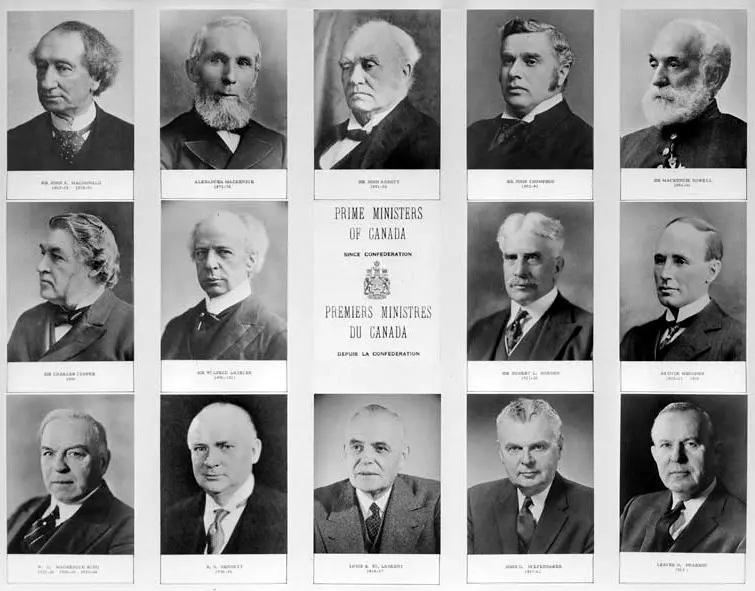

Six months before the outbreak of the Second World War, Prime Minister Mackenzie King predicted that Canada would never again send its army overseas. “The days of great expeditionary forces ... crossing the oceans are not likely to recur,” he said in March 1939. It was wishful thinking.