Commentary

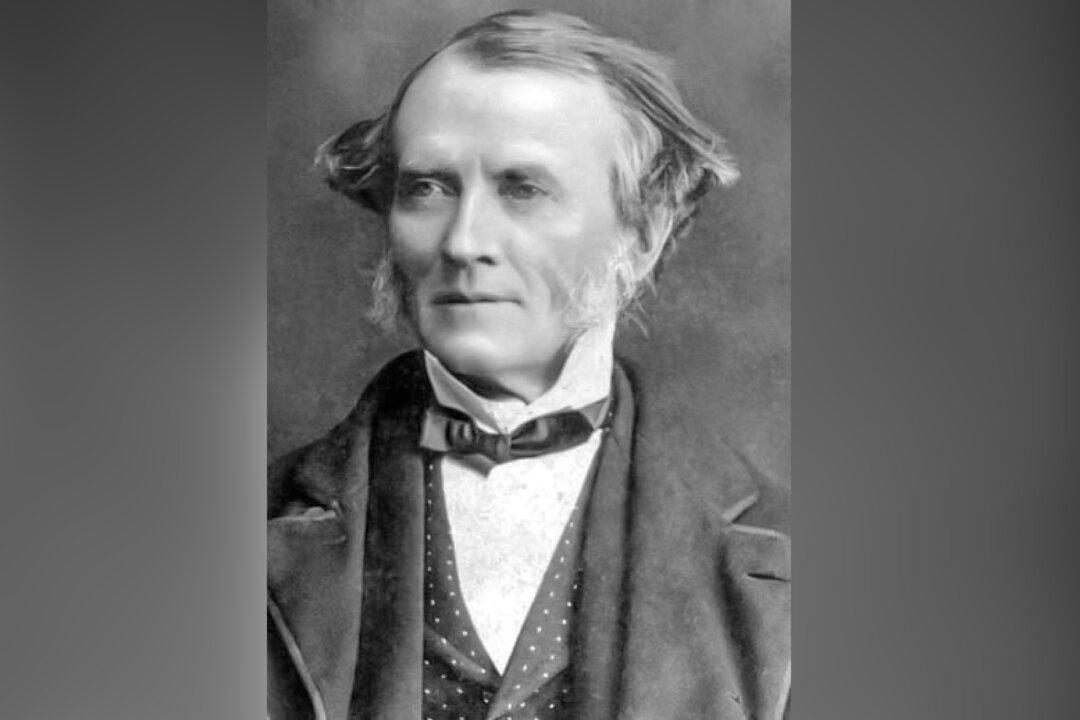

John Sandfield Macdonald was Canadian born and bred—something that was unusual among his political contemporaries. Born in 1812 in Glengarry, Upper Canada, he died in 1872 in Cornwall, only 30 kilometres from his birthplace. About 500 Scottish Highlanders had settled in eastern Ontario in 1786, in the aftermath of the American Revolutionary War, under the leadership of the Catholic priest Alexander Macdonell, trained at the Jesuit Scots College in Rome. Macdonell rallied his people to the Crown and the Upper Canadian elite. Glengarry was thus an old fashioned “Tory” milieu, dedicated to the monarchy and the British Constitution.