Commentary

One of the biggest global risks today is that China develops powerful artificial intelligence (AI) and uses it against the United States and other democracies.

China’s AI companies could power a future drone army, invent a killer virus that only targets people in North America, or create millions of virtual personas to chat with and convince U.S. citizens to vote in ways that support the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). AI can probably discover a thousand other ways to make life difficult for democracies.

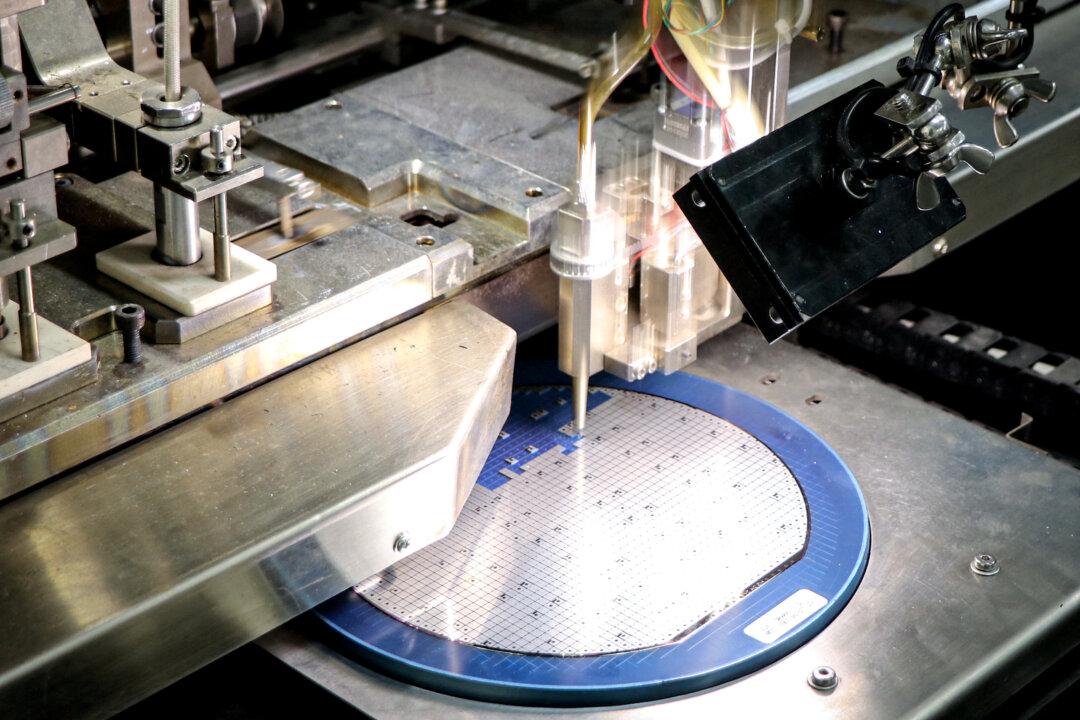

The United States, Japan, Taiwan, and the Netherlands operate or make the machines that fabricate the most advanced AI chips. Since President Donald Trump’s first term, the United States has led U.S. allies in imposing increasingly strict controls to decrease chip exports to China.

On June 16, for example, Taiwan aligned with U.S. export controls against hundreds of entities in China, Russia, Pakistan, and Burma (Myanmar), including China’s Huawei and Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC). Unfortunately, Taiwan is the only country, other than the United States, that has imposed export controls on Huawei and SMIC.

China has many other ways to access the chips it needs for AI. In late 2024, Taiwanese chips were found in a Huawei AI processor after apparently being shipped to a different Chinese company. Of course, if any Chinese company can buy the chips from Taiwan or the United States, the CCP will ensure those chips are transferred to other Chinese companies as needed. Beijing also threatens to control exports of rare earth elements (REE) to try and force the United States and allies to relax more of our controls on chips, or not enforce the ones we have.

China is only about one year behind the United States in large language models (LLMs), and two years behind in semiconductor design, according to some sources. Between 2000 and 2023, CCP-backed venture funds invested $184 billion in China’s AI startups. There are now at least 4,300 AI companies and 100,000 AI engineers in China. By 2030, the sector’s value in the country may reach $1.4 trillion.

Like all AI, China’s LLMs require the utilization of powerful chips to train neural network statistical models on huge amounts of data. First, the CCP tries to smuggle the chips, for example, those produced by Nvidia, into China. Second, it develops its own chips, albeit weaker, that it bundles together. Third, it develops better ones. China’s Huawei will be able to produce 200,000 AI chips in 2025. Fourth, it tries to export its data to export-controlled chips in third countries through cloud services or by physically transporting hard drives to a location where Chinese AI scientists can access the export-controlled semiconductors. Once the scientists train the LLM abroad, they bring it and the data back to China. As the saying goes, if the mountain will not come to Muhammad, then Muhammad will go to the mountain.

The first and fourth strategies violate U.S. export controls. For example, in early March, four AI scientists from Beijing allegedly travelled to Malaysia with 80 terabytes of data on 60 hard drives in their suitcases to train a new LLM. The AI company from China allegedly rented a data center in Malaysia with 300 servers powered by export-controlled Nvidia chips. The scientists then allegedly transferred the data onto the servers, planning to train an LLM and bring it back to China.

Malaysia is not the only country whose loose laws have potentially allowed for the de facto export of AI tech to China. Vietnam, Taiwan, and Singapore have all reportedly been used by smuggler networks to transship AI-capable semiconductors. In some cases, the smugglers transship entire servers full of Nvidia’s latest “Blackwell” chips.

Malaysia is apparently advising its companies not to violate U.S. export controls, as it could result in secondary sanctions. However, relying on Malaysia’s appeal to voluntarism by its companies would be a whack-a-mole strategy without the whack.

The U.S. threat against specific companies likely just causes any AI business with China to be spun off into smaller companies that do not do business in the United States, or with U.S. dollars, and so are effectively impervious to U.S. economic sanctions. To have a real impact, U.S. sanctions for such violations should be applied against an entire country like Malaysia if its laws and enforcement measures do not effectively stop the violation of U.S. export controls.

The sanctions need not be draconian. An additional 1 or 2 percent on existing U.S. tariffs imposed on countries with insufficient export controls could be enough to obtain the desired effect.