Commentary

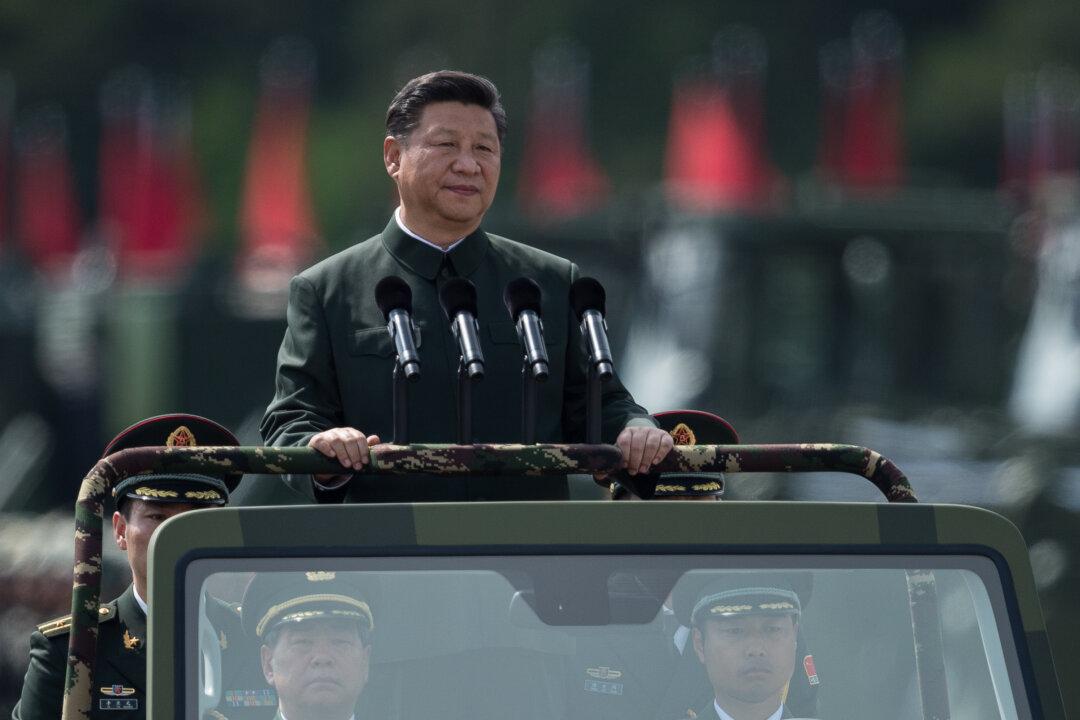

Rumors of Xi Jinping’s poor health in the wake of the BRICS summit on top of China’s collapsing economy compel us to query how long the Chinese regime will last and what will succeed it.

Rumors of Xi Jinping’s poor health in the wake of the BRICS summit on top of China’s collapsing economy compel us to query how long the Chinese regime will last and what will succeed it.