Commentary

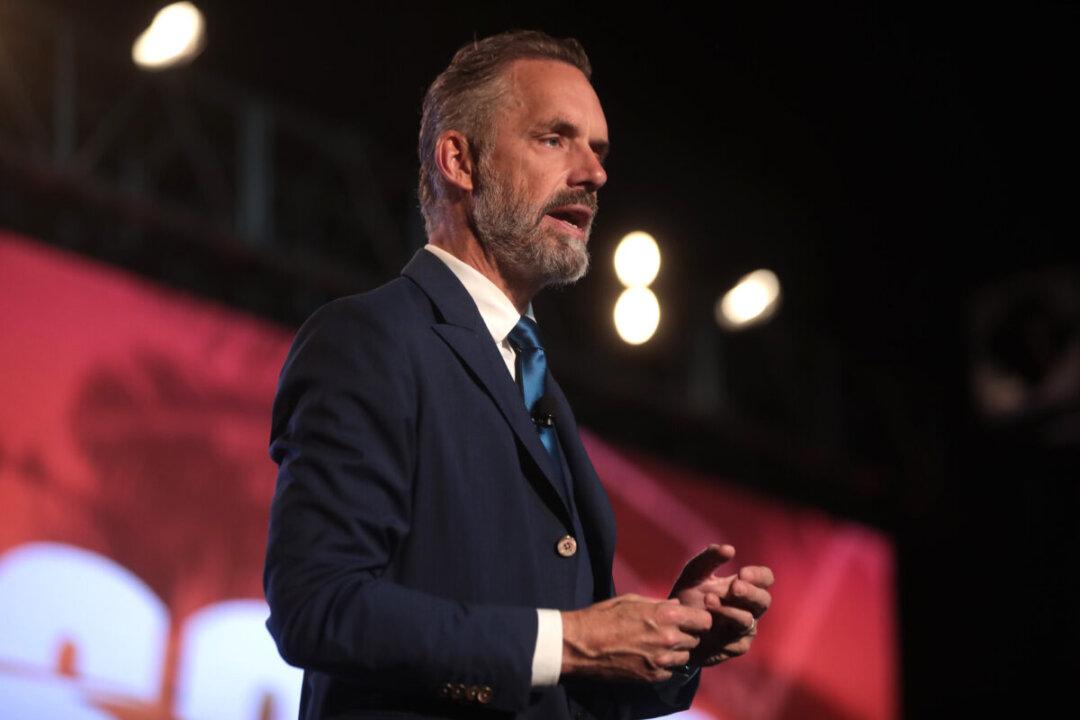

It’s been widely reported that the College of Psychologists of Ontario ordered clinical psychologist Jordan Peterson to undergo social media training, at his own expense, or risk losing his licence to practice. The Ontario Superior Court upheld the ruling claiming that courts should defer to an administrative body’s decision provided it is “reasonable.” But is it reasonable for our courts to defer to administrative bodies that increasingly believe their job is to police their members’ speech and send them to mandatory re-education camp?