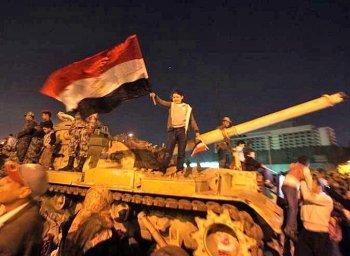

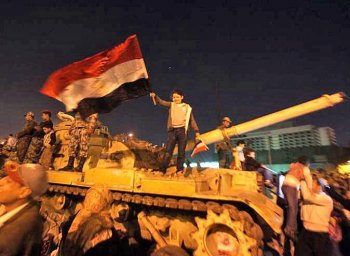

WASHINGTON—As the jubilation at the ousting Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak subsides, what lies ahead for Egypt’s future is far from clear. President Obama’s statement following Mubarak’s resignation—that the Egyptian people have spoken and that “Egypt will never be the same”—begs the question of what sort of a society and government Egypt will become.

The prospects for Egypt joining the club of liberal democracies was being hotly debated even before Mubarak surrendered power. In these discussions, the focus turns on two things: First, the military, a highly respected institution in Egypt: Second, the likelihood of Egypt’s largest and best-organized opposition group, the Muslim Brotherhood, seizing power and possibly undermining Egypt’s chance of becoming a pluralistic, secular democracy.

The first obstacle to a free and democratic Egypt could be the armed forces, which assumed power upon Mubarak’s resignation on Feb. 11.

Just before the announcement of Mubarak’s departure, the supreme military council issued a communiqué in which it promised to carry out constitutional reforms, to transition to a democracy with “free and fair” elections and end the 30-year emergency rule—once things had calmed down.

The state of emergency was invoked at the time of President Anwar Sadat’s assassination in 1981 and was never rescinded. It allows the arbitrary arrest and indefinite detention of anyone without charge. The protesters despised the perpetual martial law decree that has been used to suppress dissent.

On Sunday, the supreme military council announced that the parliament was dissolved, the constitution suspended, and that they would be running the country for six months or until elections occur. The military will also appoint a committee to amend the constitution and the people will have an opportunity to vote on those changes.

The Egyptian military has always been respected since it overthrew the monarchy in 1952. In contrast to the security forces, which Mubarak’s regime used to provoke violence and break up the protests, it is not feared. This respect is not something the military wants to lose.

In a final communiqué on Feb. 11, the military “saluted” the martyrs who gave their lives to remove autocratic rule, about 300 people. Throughout the 17 days of protests, the military did not fire on the protesters.

Defense Secretary Robert Gates said during the protest period that the Egyptian military had conducted itself in “exemplary fashion” and had acted with “great restraint.”

On the other hand, the military enjoyed great economic and social advantage during Mubarak’s rule and might want to hold on to that. At the moment, the military says the take-over is temporary. But fears naturally arise that they could install another Mubarak-like figure to run the country. Mubarak himself had been an Air Force officer when he rose to power. Once he imposed the state of emergency, he never lifted it during nearly 30 years in office.

This is not to say that the military necessarily has bad intentions, but there might be some pressure in that direction as Hisham Melhem Washington bureau chief for Al-Arabiya TV, told PBS Newshour, the day Mubarak resigned. “If we are talking about real reform, if you are talking about real civilian control of the military, if you talk about rule of law, if you are talking about all of these things, I bet you that some in the senior officer corps in Egypt … will resist these changes.”

Prospects for Liberal Democracy

In a statement made Feb. 10 before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Deputy Secretary of State James B. Steinberg, stated that the U.S. long-terms goals for Egypt and the Middle East are towards transitioning to “free and fair elections and durable, sustainable democracy.”

“We will support principles, processes, and institutions—not personalities. We are hopeful that Egyptians can lay the groundwork not just to elect new leaders, but to reform laws, build institutions, and respect the rights of religious minorities and women.”

But Samuel Tadros, founder and Executive Board member of Egyptian Union of Liberal Youth, said it is not so simple. A liberal democracy is not a matter of “wanting it,” like ordering something off a restaurant menu. Speaking at the Hudson Institute, Feb. 8, Tadros, an Egyptian moderate, said before Egyptians can establish a liberal democracy, including the rule of law, opposition parties, respect for minority rights, independent judiciary, etc., institutions need to be built and these were lacking in Egypt under Mubarak’s autocratic rule.

Tadros was a member of a panel at the conservative think-tank, the Hudson Institute, which discussed, “Egypt, Its Revolution and Future: How Should the U.S. Respond?” The panelists believed that what we are seeing is not the first stage of a liberal democracy coming to fruition, but rather the “Egyptian army taking power,” or, in the words of Lee Smith, senior editor of the Weekly Standard, “a preemptive military coup.”

Tadros said that the army never liked Gamal Mubarak, Mubarak’s son and his chosen successor; it felt Gamal Mubarak threatened its control of the economy, which is estimated to be 40 percent.

Muslim Brotherhood

Mubarak allowed only token opposition. His National Democratic Party (NDP) controlled more than 90 percent of the seats in the Parliament—a condition that the Egyptian constitution permits and the opposition demands to be changed.

Mubarak’s main opponent in the 2005 presidential election, Ayman Nour, placed a distant second in the election. He was imprisoned for four years on charges that Nour claimed were politically motivated. The U.S. apparently agreed which is why the White House repeatedly called for Nour’s release.

The Muslim Brotherhood, however, was more successful in forming an opposition. Despite being banned since 1954, Mubarak could not wipe out the popular organization. Ian Johnson writes in “A Mosque in Munich,” that the Brotherhood is illegal but tolerated. The Brotherhood was not allowed to run a presidential candidate, but was permitted to run candidates for Parliament, where it won 20 percent of the vote.

Next: The Brotherhood flourished when civil society was restricted