Commentary

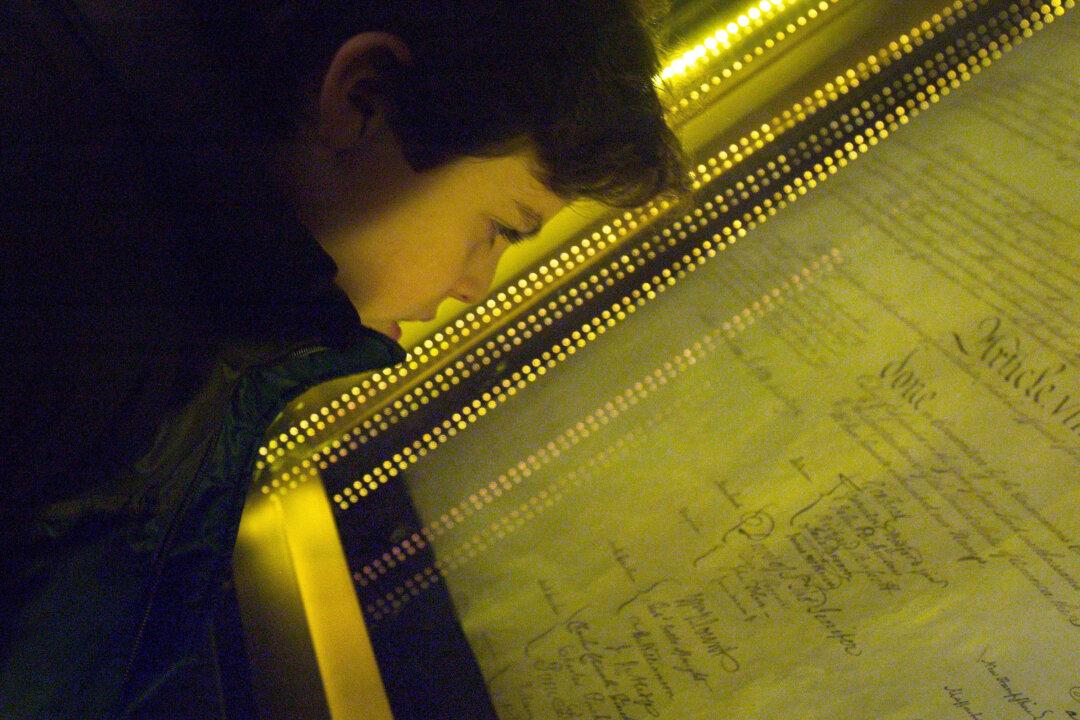

As America moved from considering itself a republic, or, as we sometimes say, a democratic republic, to thinking of itself as simply a democracy, the Electoral College has been challenged for being insufficiently democratic. Though the way we elect presidents has changed and democratized over time, the basic institution has proven resilient in the face of the many attempts to abolish it outright.