Why do we tend to think this way? Actually, the reason traces back to the game’s rise in popularity during the Great Depression, when millions of young bridge players (yes, young bridge players) able to afford the simple game gear—a single deck of cards—found themselves happy to have something intelligent to do to occupy their minds during the long periods without work.

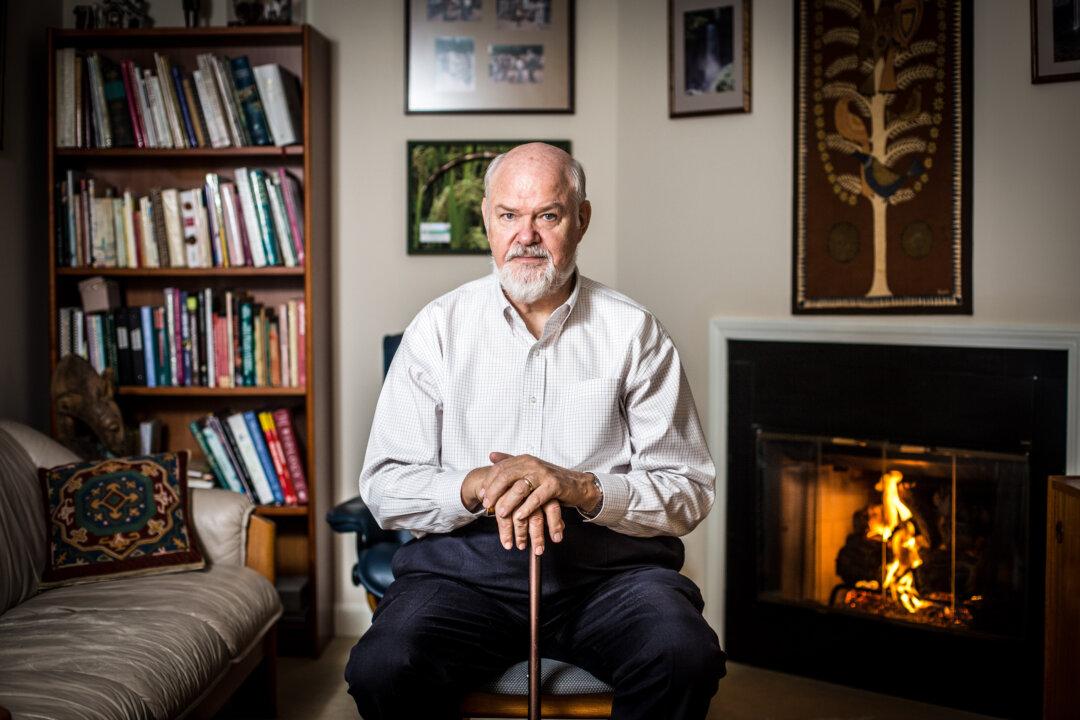

“As the economy went bust in the 1920s and 30s, the card game of bridge boomed,” explained Jeff Bayone, co-owner with Jesus Arias of one of New York’s largest and oldest bridge clubs, the Manhattan Bridge Club.

“Every little old lady there [playing bridge in his club] is a little girl inside, and she is remembering when she was 20 and just learning the game,” Bayone added.

Bridge’s earliest ancestry traces back to the 16th century British aristocracy’s favorite, Whist—a game like bridge involving partner play, bidding, and trump (the suit deemed highest during the bidding process).

Mr. Harold Vanderbilt, an American, revamped the game (a former version was called auction bridge) in 1925, and called it contract bridge. His version became so popular in the 1930s that it is still played today largely as he proposed. It was a game whose time had come.

Playing the Game

All it takes is one deck of cards, four players, and a bit of knowledge, and the intrigue of the game begins. In attempt to let their partners know what’s in their hand, players bid in a coded language and together come up with how many hands they think they can win. As the hand is played, each card has meaning for others at the table, depending on how and when the card is played.

“I would argue that bridge is the smartest, most exciting and social card game,” Bayone said.

A recent convert to the game is Microsoft’s Bill Gates, who learned from Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway. Both frequently visit bridge tournaments throughout the country. Just this month, the World-Herald reported that Gates and Buffet were at the Nebraska Regional Bridge Tournament, playing with professional partners.

“Once you know the basics, it’s very straightforward,” Gates told a CBS news anchor. “I mean, the high card takes the trick. It’s deliciously simple in the rules, but deliciously complex in doing it well.”

So complex, Gates added, that it hasn’t been mastered by computers.

Learning Bridge

It takes over three hours to play a game of 28 hands, and one needs to play two to three games a week to get really good at it.

Outlined in his beginners’ bridge book “It’s Bridge Baby: How to Be a Player in 10 Easy Lessons,” Bayone claims kudos for revolutionizing a 10-lesson bridge teaching method, which emphasizes understanding over memorization, before the approach was widely adopted.

“If you don’t memorize but understand it, there is really nothing to forget,” Bayone says of his method.The most common bridge students are women in their 50s who call up the club saying they remember how much their parents enjoyed the game. Their parents never taught them, but now they want to learn.

Most Points Win

Tournaments, as well as clubs, offering duplicate bridge tournaments are the bedrocks of the sport.

In duplicate bridge, a machine deals the cards, and everyone in the room works the same set of cards. Players compete against each other based on the skill of how well they play the hand.

“This makes it a competitive situation where the element of luck is reduced to very, very little,” Bayone said.If you prove the best at a particular hand, you win Master points—a ranking system run by the American Contract Bridge League (ACBL). Get 300 points and you achieve the rank of Life Master.

“Whoever dies with the most points wins,” Bayone said.

According to Bayone, ACBL is by far the biggest user of convention space in the world. In a typical month, 25 tournaments are booked. The numbers of participants range from hundreds to thousands, depending on whether the tournament is local or regional. National events attracting upwards of 5,000, occur three times a year.

The bigger the tournament, the more points are available for the winning.

Bridge in Schools

The ACBL, the game’s organized authority, is aggressively reaching out to youth in hopes of engaging a new generation of bridge players.

A web portal, youth4bridge.org, runs ambassador programs, offers scholarships and provides lessons and programs to encourage young bridge players.

A fully funded School Bridge Lesson Series offers free textbooks and stipends to teachers willing to introduce the game. School administrators see math, critical thinking, and social skills as valuable teaching lessons.

In 2005, their programs gained significant muster when Gates and Buffett offered $1 million dollars to promote bridge in schools.

According to the ACBL, more than 4,000 youngsters participate each year.

Bridge in New York

Bayone got involved in bridge as a young person after playing in a chess club. He discovered that bridge was as challenging as chess, but much more interactive, faster paced, and more fun to play.

When the Colony Bridge Club that Bayone frequented shut down in 1976, he convinced the landlord to accept payment for what was owed on the property and re-opened it, renaming it the Manhattan Bridge Club and offering much better snacks than the previous owner had—one of the secrets of his success.

At his current location on West 57th Street, Bayone boasts one of the oldest and largest daily clubs in the country, catering to 2,000 players a year. A smaller sister club on the East Side caters more to beginners.

It costs around $20 dollars to play a game, and two to three tournaments are offered daily. On Friday and Monday nights, the club also caters an extensive buffet dinner that people can enjoy prior to the evening round.

One of the Manhattan Club regulars, Herb, used to arrive at the club for years with an oxygen tank and a walker. According to Bayone, he would enjoy himself greatly, yelling and screaming sometimes over the card play along with the others. But on Tuesdays and Thursdays, Herb would rush off after the game, and Bayone never understood why.

When Herb passed away about a year ago and Bayone went to sitting shiva to pay his respects, he met the man’s daughter, who explained that Herb used to set up his dialysis schedule around his bridge games—he left in a rush because he needed to get to the hospital.

“This was his life. This is what he loved,” the daughter had told Bayone, he recalled.

“For so many of the people here, as they get older, this becomes more and more their life,” Bayone said.

Other bridge clubs on the New York scene are the Cavandish Club on 87th Street and the Honors on 58th Street. Both clubs cater largely to the pros, according to Bayone.