It was the height of the financial crisis, and Sam Polk, a senior millionaire trader at one of Wall Street’s largest hedge funds, was feeling like the odd man out.

While his colleagues obsessed and fretted about how new government regulations would impact their bonuses, he was thinking the regulations might be good for the system. Polk couldn’t shake his sinking feeling that the system was broken.

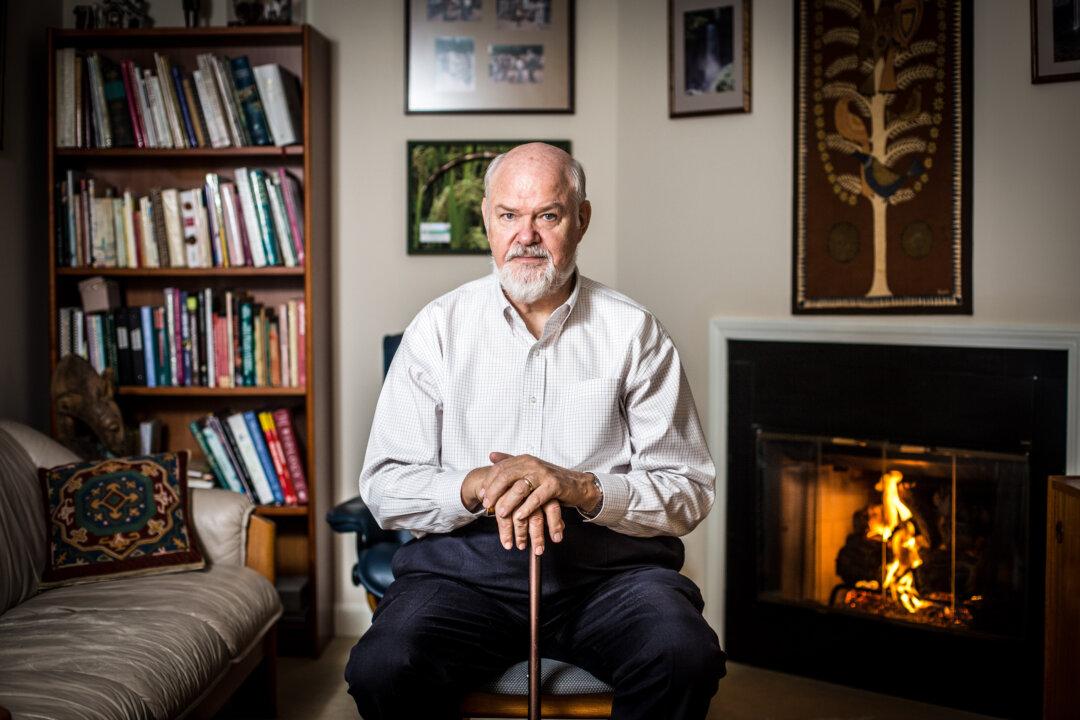

After he got up the courage to quit his high-rolling lifestyle, Polk went through a period of internal reflection and decided he wanted to start a nonprofit, teaching caregivers in low-income communities in South Los Angeles about a healthy approach to food. He had gone through his own fair share of food issues in life, so working with food made sense.

But Polk soon realized that even if people had the groceries in hand, they had no time to cook. So he designed a for-profit business model in which he could sell packaged meals at a reduced price. Polk sees his social enterprise as involving the community in an exchange of commerce they can afford, rather than charity.

“Healthy food is a human right,” said Polk, executive director of Groceryships and co-founder and CEO of Everytable, “and the fact that it is a luxury product today is not OK.”