WASHINGTON—The dissident who led the protest that set in motion the democracy movement in China modestly avoided seeking any acclaim. That acclaim has come, however, with the awarding of the “Wei Jingsheng Democracy Champion Prize” to Liu Di.

On April 5, 1976, thousands gathered in the southeast corner of Tiananmen Square in a protest directed at the Cultural Revolution and the rule of China by Mao’s heirs, the Gang of Four.

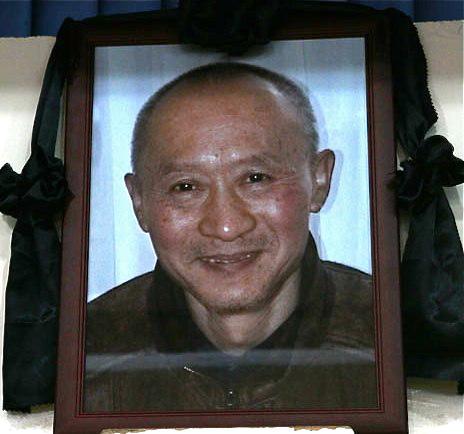

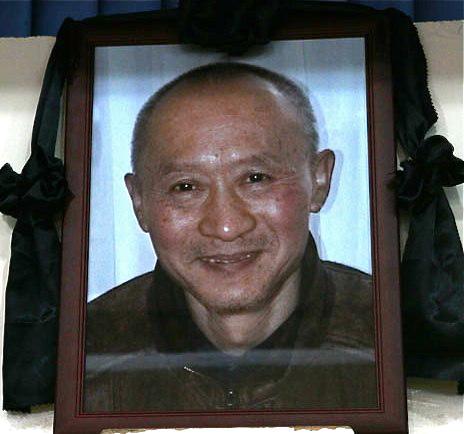

Leading the chants of the protests was a man known to most only as “the crew cut.” That man was Liu Di, and the Wei Jingsheng Foundation honored him on Dec. 5 for making a “great contribution to the cause of Chinese democracy,” as the prize announcement said.

Liu, 61, passed away from cancer on Oct. 19 in China, before he could hear the news that he had won the prize.

The April 5 protest was groundbreaking. “In 1976, people had already begun to disbelieve in the deception of the Communist Party,” said Wei Jingsheng, as quoted in foundation’s statement read by Executive Director Ciping Huang at the dedication ceremony. “However, at that time, extremely few people openly opposed the Communist Party. ... Most people still believed in the Communist Party.”

Liu was blacklisted, became a fugitive, and eventually served 10 months in jail, until the regime reversed itself.

The 1976 protest “initiated the waves [of protests] demanding democracy in China,” said the prize announcement.

“In the past 35 years, Liu Di ... has done a lot of work unknown to most others,” said Huang. “He was not absent from any of these movements, from the 1978 Democracy Wall to the 1989 occupation of Tiananmen Square, until his last breath.”

Eddie Cheng, author of Standoff at Tiananmen, wrote on his blog, “During the 1989 student movement, Liu Di was one of many older intellectuals who volunteered to assist and advice (sic) student leaders from behind the scenes. ... After the massacre, Liu Di was arrested on July 10, 1989, and spent nine months in jail. During the 1990s, he was active in raising international awareness of the human rights conditions of political prisoners in China.”

During the 1978 Democracy Wall movement, Liu founded the publication Beijing Spring.

Wei Jingsheng also played a lead role in the Democracy Wall Movement. There was a long brick wall on Chang'an Street in the Xidan District of Beijing, where people were allowed to post statements during a brief period of relative openness under Deng Xiaoping following the end of the Mao era. The most famous statement, which launched the Democracy Wall Movement, was the Fifth Modernization, posted by Wei, who signed it and placed it on the wall on Dec. 5, 1978—the same date as the awarding of the Wei Jingsheng Chinese Democracy Champion Prize.

Wei had the temerity to say something vital was missing in the communist state, namely, democracy. Wei was imprisoned over 18 years of his life, including many years in solitary confinement, for his democracy advocacy. President Clinton was able to secure his release to receive medical treatment in the United States.

In the United States, Wei founded the Wei Jingsheng Foundation in 1998 in Washington, D.C., which is dedicated to the promotion of human rights and democratization in China. He himself has won numerous honors including the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought and the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award.

Content with His Lot

Liu was closely monitored and supervised by the communist authorities after his release from prison in 1990 for his role in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protest, and was never free of being persecuted, according to the foundation statement. He therefore was unable to hold a permanent job and always lived in poverty.

Liu’s dissidence continued in spite of his straitened circumstances. The dedication statement highlighted his character and his knowledge of life.

“His knowledge came from his insight and experience with the plight of the people when he was in the countryside at a young age, as well as from his tireless study and a deep grasp of the essence of traditional Chinese culture,” said Huang. “This background made Liu Di full of chivalry, warmth, love, and modesty in his personality.”

Huang said that a distinguishing feature of Liu was his silent self-sacrifice. “We were surprised to find that Liu is the most low-key democratic activist we have seen.”