It’s been said, and it was—just earlier this month by the Canadian Chamber of Commerce—that it can be easier to trade with a foreign country than with another province.

But Alberta Premier Jason Kenney is doing his utmost to change that, by taking a leadership role in dropping barriers that prevent greater commerce between his province and others.

Getting rid of trade barriers between Canada’s provinces and territories has the potential to help unify the country after a divisive federal election, according to Peter St. Onge, senior economist with the Montreal Economic Institute (MEI).

“There are huge benefits in terms of reinforcing that we are all Canadians. We’re all in this together,” St. Onge said about dropping protectionist stances. “This is perfect timing, unfortunately, with the conflicts between people in Alberta and specifically in Quebec, but also among the other provinces that are not as welcoming about importing energy.”

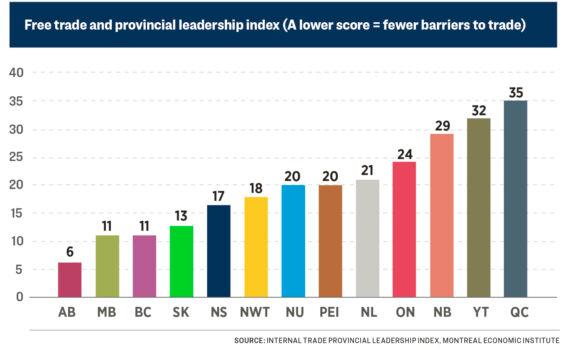

St. Onge is a collaborator on a research paper introducing the MEI’s newly created Internal Trade Provincial Leadership Index (ITPLI). The ITPLI, launchedNov. 14, was established primarily to track progress toward a Canada free of internal trade barriers, which could raise economic growth by almost 4 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund.

The index ranked the 10 provinces and three territories based on having the fewest barriers to internal trade. Alberta ranked No. 1, thanks to Kenney’s efforts to eliminate large swaths of trade exceptions from the Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA).

The index ranked the 10 provinces and three territories based on having the fewest barriers to internal trade. Alberta ranked No. 1, thanks to Kenney’s efforts to eliminate large swaths of trade exceptions from the Canadian Free Trade Agreement (CFTA).

The CFTA, a joint project of the federal, provincial, and territorial governments, took effect in 2017 and was intended to be a significant step toward freeing up trade in “virtually every sector of the economy,” as noted by the federal government at the time. However, it’s so loaded with exceptions that it prompted the MEI, in collaboration with the Canadian Constitution Foundation, to create an index to monitor advancement toward eliminating those impediments.

Alberta ‘Doing the Right Thing’

Government procurement is one such crucial area filled with multiple exceptions.

The report also points to sections in the CFTA that support monopolistic behaviour at the provincial level if the government owns the monopoly. For example, Article 317 allows the provinces to discriminate against external investors in order to protect a monopoly.

“The perfect is the enemy of the good is the logic there,” St. Onge said, adding that by creating the index, it keeps pressure on the provinces and territories to get rid of awkward rules, special fees, certain licensing requirements, etc. that hinder commerce.

Simply put, the index appears to show that Canada has some provinces that want free trade and others that don’t. The western provinces of Alberta, Manitoba, B.C., and Saskatchewan lead the rankings while Quebec ranks last.

“By unilaterally disarming on protectionism, Alberta Premier Jason Kenney is doing the right thing. … This is going to be an easier province to invest in, to make money in, to hire people in. That’s positive for an economy,” said the research report’s author, MEI senior fellow Mark Milke, in an interview with BNN Bloomberg.

It’s also good for Alberta to diversify its economy, and it promotes national unity, Milke added.