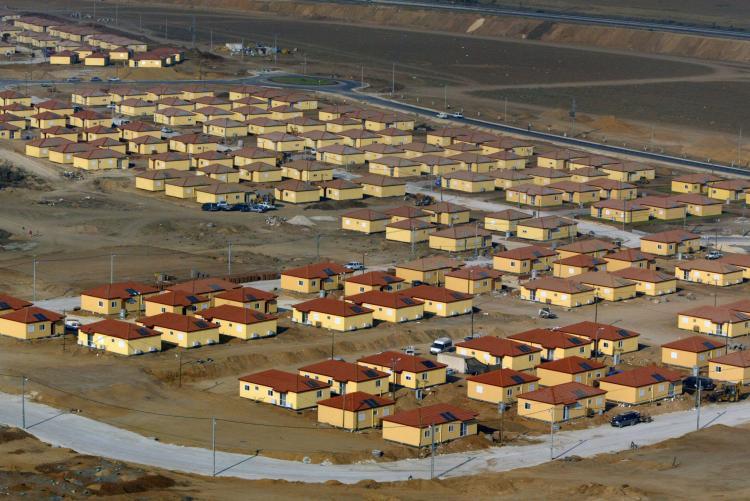

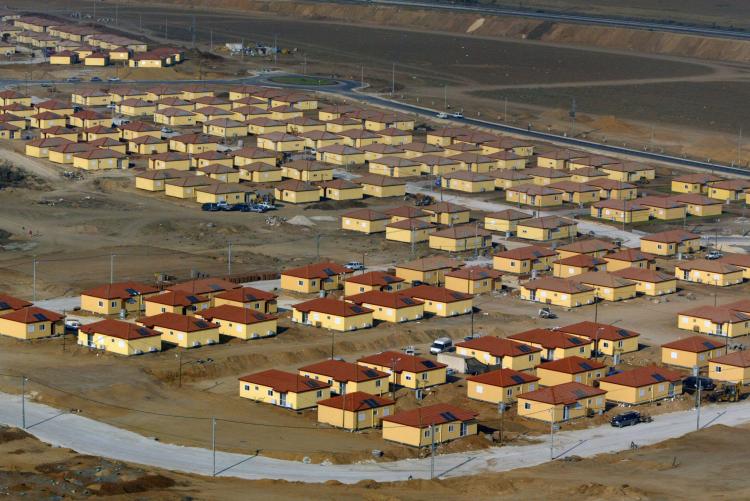

NITZAN, Israel—In the dusty land of southern Israel, in a small town called Nitzan about 500 families were tossed to the wind five years ago. The families, former residents of an area in Gaza called Gush Katif, were evacuated in August 2005 by the Israeli government in their program of “disengagement” in Gaza.

What struck me first upon meeting some of these people—who called themselves evacuees—is how much they have in common with the survivors of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. They even share an anniversary: August marks five years since the storms devastated New Orleans, its residents, and the entire country.

I spent some time in New Orleans and surrounding areas two years after the hurricanes. People were barely beginning to pick up the pieces of their lives. And at that point, new housing construction could be found mostly in the wealthier, whiter neighborhoods. The areas closest to the levee that broke—such as the lower income neighborhoods with almost no white residents like the Ninth Ward—were eerie ghost towns of weeds, empty foundations of homes, and stairs leading nowhere.

Three years after I saw the shadow of New Orleans, I saw a similar shadow in the residents in Nitzan. People in both places were indignant and angry at their government for the layers of bureaucracy that they say stands in the way of their recovery.

But to see such a similar despair come from such different circumstances seemed almost insincere.

In New Orleans, they had about two days warning that a major storm was coming. Many people who didn’t leave the city had no means of transportation. In Gush Katif they were given months to prepare.

In New Orleans, the storms struck with such fury that residents were trapped in their houses. Some suffocated in attics, scratching on the ceiling as the water enveloped them when the levee broke. Those who survived the water faced the nightmare of being trapped on their roofs, or in their houses with no way to navigate the swamp of toxic water swirling around them. Dead bodies floated past. Many begged to be rescued, yet many died waiting for help.

In Gush Katif, people also stayed entrenched in their homes, but it was intentional. They sat stubbornly on rooftops as the Israeli army and police descended on their community to remove them by force. During my trip to Nitzan and in the course of hearing several speeches from former Gush Katif residents, their experience was described repeatedly as a tragedy. Many people bitterly blamed former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, a man who has laid in a coma for several years now, practically cursing his name.

To lose a home and a life built from scratch, like the residents of Gush Katif did, must have been a terrible blow. But the residents of New Orleans pose a much more tragic picture in my mind. After the storms subsided, families were tossed to every corner of the United States, a vast geographic area. Parents and children were separated, sometimes only reunited in memory when the news of death came. And the government’s incredibly slow and bumbling response to the tragedy is infamous.

Many of the Israeli residents who were relocated from the Gaza Strip have moved on with their lives. But maybe those who continue to dwell on the inequities of their situation should take a good look at what happened in New Orleans that same month five years ago.

The survivors of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita were called “refugees” by their own country, yet have managed to move forward, mend the pieces, and move on. The former residents of Gush Katif might find some inspiration from the former and current residents of New Orleans and their lesson to the world: sometimes the greatest triumphs in life stem from the ability to move past disappointment.

What struck me first upon meeting some of these people—who called themselves evacuees—is how much they have in common with the survivors of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. They even share an anniversary: August marks five years since the storms devastated New Orleans, its residents, and the entire country.

I spent some time in New Orleans and surrounding areas two years after the hurricanes. People were barely beginning to pick up the pieces of their lives. And at that point, new housing construction could be found mostly in the wealthier, whiter neighborhoods. The areas closest to the levee that broke—such as the lower income neighborhoods with almost no white residents like the Ninth Ward—were eerie ghost towns of weeds, empty foundations of homes, and stairs leading nowhere.

Three years after I saw the shadow of New Orleans, I saw a similar shadow in the residents in Nitzan. People in both places were indignant and angry at their government for the layers of bureaucracy that they say stands in the way of their recovery.

But to see such a similar despair come from such different circumstances seemed almost insincere.

In New Orleans, they had about two days warning that a major storm was coming. Many people who didn’t leave the city had no means of transportation. In Gush Katif they were given months to prepare.

In New Orleans, the storms struck with such fury that residents were trapped in their houses. Some suffocated in attics, scratching on the ceiling as the water enveloped them when the levee broke. Those who survived the water faced the nightmare of being trapped on their roofs, or in their houses with no way to navigate the swamp of toxic water swirling around them. Dead bodies floated past. Many begged to be rescued, yet many died waiting for help.

In Gush Katif, people also stayed entrenched in their homes, but it was intentional. They sat stubbornly on rooftops as the Israeli army and police descended on their community to remove them by force. During my trip to Nitzan and in the course of hearing several speeches from former Gush Katif residents, their experience was described repeatedly as a tragedy. Many people bitterly blamed former Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, a man who has laid in a coma for several years now, practically cursing his name.

To lose a home and a life built from scratch, like the residents of Gush Katif did, must have been a terrible blow. But the residents of New Orleans pose a much more tragic picture in my mind. After the storms subsided, families were tossed to every corner of the United States, a vast geographic area. Parents and children were separated, sometimes only reunited in memory when the news of death came. And the government’s incredibly slow and bumbling response to the tragedy is infamous.

Many of the Israeli residents who were relocated from the Gaza Strip have moved on with their lives. But maybe those who continue to dwell on the inequities of their situation should take a good look at what happened in New Orleans that same month five years ago.

The survivors of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita were called “refugees” by their own country, yet have managed to move forward, mend the pieces, and move on. The former residents of Gush Katif might find some inspiration from the former and current residents of New Orleans and their lesson to the world: sometimes the greatest triumphs in life stem from the ability to move past disappointment.