NEW YORK—It’s been 17 years since the Chinese Communist Party made the fateful decision to eliminate Falun Gong, one of the largest religious communities in China.

Practitioners of Falun Gong, a popular, traditional discipline of qigong with moral teachings and physical exercises, have hotly contested the persecution, often at huge personal cost.

A recent interview with the wife of a schoolmate of China’s former leader Hu Jintao illustrates the complexity of how the campaign played out in the lives of ordinary Chinese, and how it brushed up against the leader himself.

Hu, despite being general secretary of the Communist Party, appeared to have been powerless to protect his former schoolmate from persecution—a persecution that had been ordered by his immediate predecessor Jiang Zemin, a few years before he rose to power. Jiang’s decision to strike out against Falun Gong in 1999 was both highly controversial and highly personal.

Speaking in Mandarin with the Cantonese lilt of China’s southern Guangdong, Luo Muluan told the tale of what she and her late husband Zhang Mengye experienced—encounters with Hu Jintao and his wife Liu Yongqing during college reunions, tense meetings with their old schoolmates sent as envoys after the persecution started, and their final escape to Thailand, before she came to the United States alone.

Today, Luo, the archetype of a Chinese “auntie,” with curled hair and large sunglasses, lives in Brooklyn, and frequents the borough’s Chinatown for her voluntary activism. It’s there that she encourages her compatriots to renounce the political party that drove her and her husband from their homeland.

‘You’re Finally Here’

In April 1995, Zhang Mengye and Luo Muluan were warmly received at the gates of Beijing’s Tsinghua University—also called “China’s MIT”—by Zhang’s classmates.

“You’re finally here; we can finally meet up with you,” Luo recalls Zhang’s classmates as saying. It was the first time anyone had seen him in three decades.

Since his schooldays, Zhang had suffered from chronic liver problems. After graduating, he remained thin, frail, and at one point, near death. Zhang’s poor health prevented him from leaving his native Guangdong Province in southern China to attend college reunions in Beijing.

In the early 1990s, Zhang started trying out qigong—a traditional Chinese energy exercise that people took up for health and wellness—as an alternative treatment for his ailments. In 1994, he attended a series of lectures by Li Hongzhi, the founder of Falun Gong. Zhang was drawn to Falun Gong’s gentle exercises, and teachings of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance.

After eight months of practice, Zhang felt fit enough to make the long northward journey to Tsinghua. Hu Jintao, then head of the Chinese Communist Party’s Secretariat, and his wife Liu Yongqing, were also present at the 1995 class reunion. When everyone had gathered on campus, Liu encouraged Zhang Mengye to give a speech.

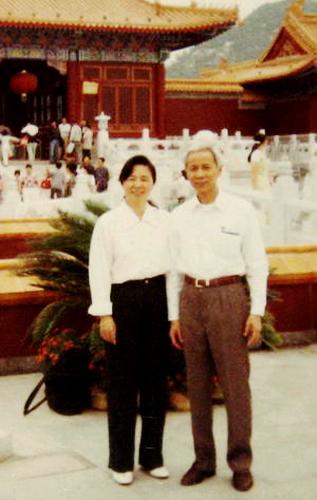

So Zhang got up on stage and related the story of how his health had vastly improved since he started practicing Falun Gong. When he was done, Hu Jintao’s wife led the applause with enthusiastic clapping, according to Luo. She later insisted that Zhang and his wife pose with Hu and herself for a standalone picture during the group photo taking session at the ceremonial Great Hall of the People. (Luo Muluan kept the photographs, but was unable to bring them with her when they fled China.)

Over the next few years, Zhang’s story was becoming commonplace across China. Many experienced remarkable improvements in health and mental well being through Falun Gong, which remains free to practice. By 1999, a state survey counted 70 million practitioners of all ages and professions, while Falun Gong sources often estimated 100 million.

Zhang Mengye and Hu Jintao met for the last time at another Tsinghua reunion on April 24, 1999. When the Zhangs got back to Guangdong, they received a phone from a Tsinghua classmate in Beijing.

“Did you participate in the Falun Gong petition at Zhongnanhai on April 25?” the classmate asked.

“If we had known, we would most certainly have participated,” Zhang replied.

Activism and Pushback

On April 25, about 10,000 Falun Gong practitioners journeyed to Beijing to petition the central government to free practitioners who had been beaten and arrested in Tianjin days earlier.

Zhu Rongji, then Chinese premier, met with practitioner representatives and agreed to uphold the Party’s stance of staying neutral on qigong. The practitioners quietly dispersed, but not before picking up their litter and cigarette butts left behind by the police.

But that evening, then Party leader Jiang Zemin wrote in a letter to the top Party leadership, “can it be that we Communist Party members, armed with Marxism, materialism, and atheism, cannot defeat the Falun Gong stuff?” On July 20, Jiang ordered the suppression of Falun Gong.

Zhang Mengye knew that the persecution campaign was something big—“Zhang’s a Tsinghua graduate; they’re more sensitive to these sort of things,” Luo Muluan said—and became preoccupied with clearing up what he perceived to be the Chinese regime’s misunderstanding towards the practice responsible for his new-found health.

Twice Zhang and Luo tried to journey to Beijing to protest, in July and October of 1999. Both times they were stopped by security forces and sent back to Guangdong. Zhang later led Falun Gong practitioners in Guangdong to petition the provincial authorities, and tried unsuccessfully to submit letters to then deputy Chinese leader Hu Jintao.

Security forces in Guangdong were aware that Zhang and Hu were former Tsinghua classmates.

During Zhang’s first attempt to travel to Beijing in July, he and others were picked up by Hao Xiaoming, the chief of a local “610 Office,” a Gestapo-like organization Jiang created to oversee the persecution.

“Old Zhang, are you trying to go to Beijing to look for Hu Jintao? It’s no use; Hu Jintao can’t help you,” said Hao, according to Luo Muluan.

Coin Toss

Being connected with high-level Party officials could be a good or bad thing for Falun Gong practitioners.

Wang Youqun, the aide to former Party internal disciplinary chief Wei Jianxing, was one of the first Party cadres to be dismissed from his workplace and the Party for practicing Falun Gong. But for several years, Wang escaped the worst parts of the persecution, and was allowed to stay in his state-owned apartment.

Wang attributes the privileges he enjoyed to the good graces of his former boss Wei, who also sat on the powerful Politburo Standing Committee. According to Xin Ziling, a retired defense official with channels to moderate voices in the top leadership, all members of seven-man Standing Committee save Jiang had opposed the persecution of Falun Gong.

But Hu Jintao didn’t appear to be able to protect his old classmate Zhang Mengye from the ravages of the persecution.

Zhang was among the first practitioners in Guangdong to be rounded up after Jiang Zemin visited the province and criticized the local authorities for their “feeble” attempts at suppression. Despite being 60 at the time, he was thrown in a labor camp for over 750 days, according to Minghui.org, a clearinghouse for firsthand information about the persecution. Zhang emerged emaciated, and weighed only 77 pounds.

In May 2002, three months after his release, Zhang Mengye was again arrested. He was brutally tortured in a brainwashing center over the next seven months. During one torture session, guards tightly bound Zhang with ropes and repeatedly dunked him head first into an overflowing toilet bowl.

In the penultimate month of Zhang’s ordeal, Hu Jintao was officially appointed leader of the Chinese regime. Luo Muluan thinks that Jiang Zemin had sought to punish Zhang near Hu’s inauguration to make a statement—Hu might be Party leader, but he shouldn’t think about interfering with Jiang’s pet project.

Classmate Connections

Hu Jintao might not have been able to help Zhang Mengye, but it isn’t due to his lack of trying, according to Luo Muluan.

“Hu Jintao definitely knows how bad the persecution is, but he doesn’t have the power or the ability to stop it,” said Luo. “So he sent former Tsinghua classmates to persuade Old Zhang to be accommodating and lay low.” The fact that Zhang was visited by his fellow alumni at all was taken by both Zhang and Luo that they had been sent with the blessing of Hu Jintao, given that the frenzied ideological atmosphere at the time meant that anyone identified as a Falun Gong practitioner was to be isolated and struggled against.

“How else would they dare come?” she added.

A classmate from Beijing personally visited them in Guangdong in 2002, and reminded Zhang that former Party paramount leader Deng Xiaoping had been thrice purged and reinstated to office. The classmate then gently hinted that Zhang should cooperate with the authorities and stop petitioning them about Falun Gong.

“Why must you stubbornly resist,” the Beijing classmate said. In the future, “there would come a time” where Zhang could be “rehabilitated” like Deng.

“That’s impossible,” Zhang said with a smile. “What we’re doing is not politics, it’s self-cultivation! My health was restored; what’s wrong about that? Go back and tell Hu Jintao.”

Later when Zhang was detained in the brainwashing center, another classmate from Beijing called Luo Muluan, and advised: “If Zhang’s alive, you must see him in person; if he’s dead, you must see his corpse.” To Luo, this message was a clear sign that the severity of the anti-Falun Gong campaign was common knowledge among her husband’s peers.

In mid-2003, Zhang and Luo visited a classmate who was a high-ranking local official in Guangdong. Zhang recounted the torture he suffered to his classmate, and asked the classmate if he could pass a letter detailing the going-ons in the brainwashing center to Hu Jintao during one of the classmate’s frequent trips to Beijing.

But the classmate declined, and told Zhang not to be too simple minded. “If he doesn’t handle things well, Old Hu stands to…” Zhang’s classmate trailed off, drawing his finger along his neck, the gesture of decapitation.

Persecution is Personal

Chinese security forces and agents from the 610 Office eventually kept Zhang Mengye and Luo Muluan under tight surveillance. The couple were followed the moment they left their home; during the interview, Luo chuckled as she recalled enlisting the help of an agent who tailed her while she was out grocery shopping.

Petitioning Hu Jintao or the regime in general about Falun Gong became less and less feasible for the couple. They made plans of escape, and managed to elude their minders and flee to Thailand in November 2005.

In Thailand, Zhang wrote several open letters to Hu Jintao, and led other escaped Falun Gong practitioners to establish a permanent protest site outside the Chinese Embassy. In August 2006, Zhang gave his impression of Hu in college in an interview with the Chinese language Epoch Times.

In September 2006, Zhang was hit by a car that suddenly emerged from a cul de sac along a minor road. He was supposed to be sent to a public hospital, but the ambulance instead took him to a private hospital.

Although Zhang’s injuries were non-life threatening, the doctor insisted on operating. Three days later, he passed away. Luo suspects that the long arm of Jiang Zemin got to Zhang in Thailand, though others in the Falun Gong community apply Occam’s Razor to the case.

His memory, though, still serves as inspiration to his widow. “I said to myself that I should carry on Old Zhang’s work,” Luo said. “But I don’t think I’ve done quite nearly enough.”