Commentary

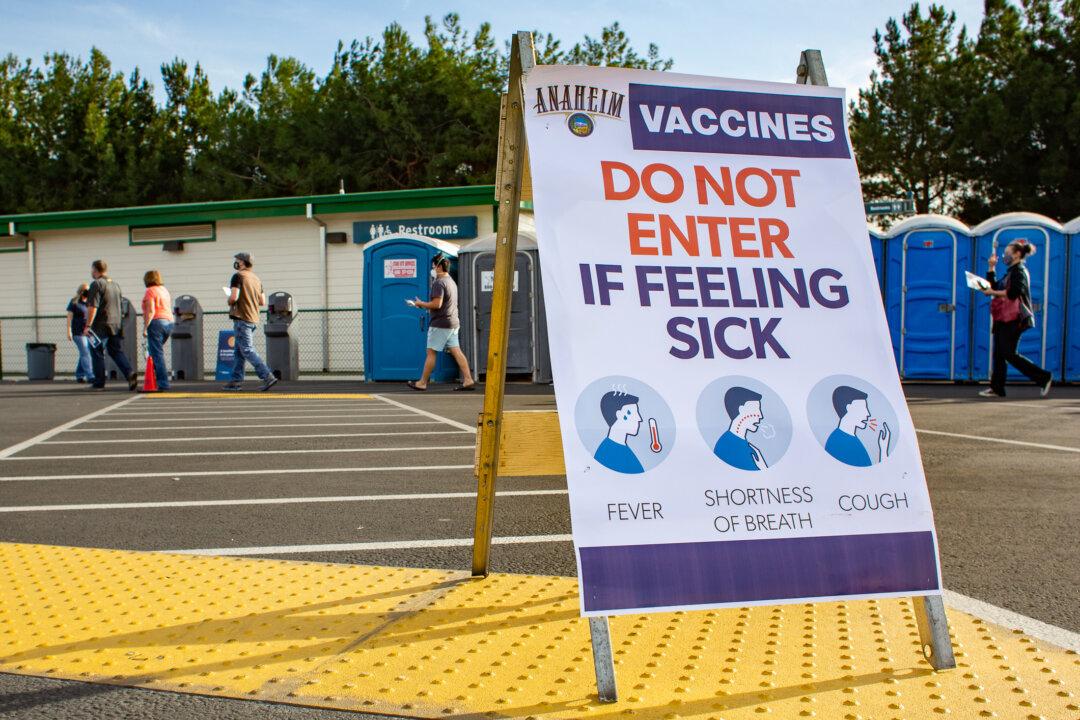

The COVID-19 lockdown was ordered by Gov. Newsom on March 4, 2020. Seeing South Coast Plaza’s parking lot empty during the middle of the day was an eerie experience. Losing sales tax revenue certainly impacted Costa Mesa. Having the Angels play without fans in the seats, a convention center not hosting conventioneers or Disneyland not admitting guests had significant fiscal reverberations for the city of Anaheim.