The presidential elections in Belarus on Dec. 19, 2010, were meant to give hope of some democratic progress that looked possible before the vote. Instead, it took the country in the opposite direction as authorities cracked down on mass demonstrations against rigged election results, immobilizing opposition politicians and leaving little hope for democratic change.

Before the December vote, opposition candidates were allowed to voice different platforms and let people know about alternatives. Some television programs critical of Belarus’ heavy-handed President Alexander Lukashenko were aired, broadcast via Russian channels, which have a solid market share in the country.

The West and East were split over reactions to the election and its fallout. Western governments strongly condemned the vote as fraudulent and criticized Lukashenko for the violent crackdown on demonstrators.

On Dec. 23, 2010, days after the crackdown and arrest of over 600 demonstrators, opposition politicians, and journalists, the United States and European Union issued a joint statement strongly condemning the violence.

“Taken together, the elections and their aftermath represent an unfortunate step backwards in the development of democratic governance and respect for human rights in Belarus. The people of Belarus deserve better,” read the statement.

From the East, Russia and other former Soviet countries deemed the elections fair and in keeping with international standards, and that anything else was a domestic affair.

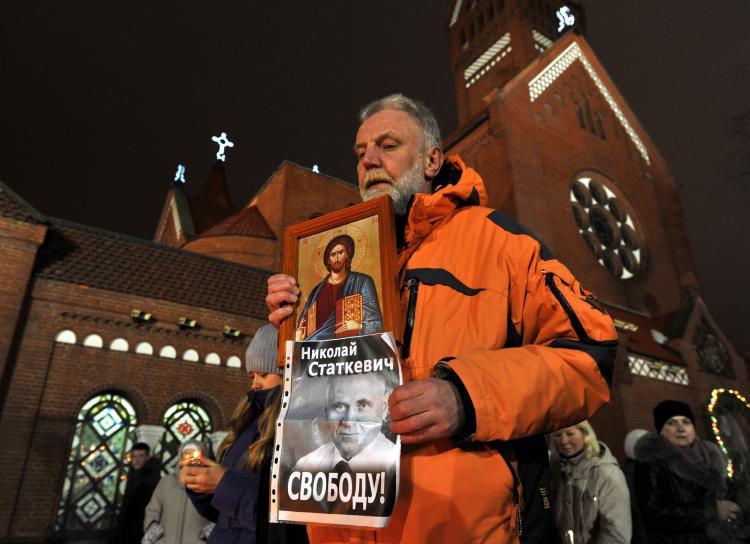

Most of the presidential candidates, journalists, and human rights activists ended up being taken into custody were accused of violating social order, and will face trial at the end of this month.

Media controlled from the capital, Minsk, bluntly accused the European Union last week, particularly German and Polish intelligence services, of being behind the election day demonstrations.

The West, meanwhile, is considering its position on imposing sanctions on top Belarusian officials. On Jan. 31, EU foreign ministers will meet to discuss its policy toward Minsk.

“It will unfortunately have to be discussed again whether we’ll have to revive sanctions that we really should have put behind us. It’s very regrettable,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel said on Jan. 14 in Berlin after a meeting with her Italian counterpart PM Silvio Berlusconi, who also supported stricter approaches toward Belarus.

“The looming question for Western leaders is whether to revive tough sanctions and close the door on engagement with the Lukashenko regime, or to seek a solution that will undo the direct post-election abuses while leaving open the possibility of future re-engagement,” the Carnegie Endowment, the global think tank, said in its recent analysis on the issue.

In 2006, Washington and the EU imposed travel and trade sanctions on Belarus following rigged presidential elections that were also accompanied by the arrest of opposition politicians. After a thaw, the sanctions were lifted two years later, with the EU taking a new policy direction of engagement, not isolation.

In 2008, Belarus was invited to participate in the EU Eastern Partnership project particularly aimed at Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine to bring the post-Soviet countries closer to the EU, and help promote democratic norms there.

This time, too, the EU has expressed that further isolation of Belarus will not bring hope for reforms and benefits for ordinary Belarusian citizens and would only serve to push the country closer to the Kremlin.

“While we express our concern to the authorities, we cannot isolate the citizens,” said Catherine Ashton, EU high representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, in a letter addressed to the European Council President Herman Van Rompuy on Jan. 19.

For the last decade, Lukashenko has also tried to balance its ties with the West and East. Minsk relies heavily on the East as a market for Belarusian-made products given customs and trade benefits mainly with Russia and Kazakhstan.

However, the last year has been a rocky one in Belarus-Russia relations, filled with political opposition, wars of words, and gas price disputes. The Kremlin has expressed its annoyance with Lukashenko for not satisfying Russian interests; for example, Belarus refuses to recognize disputed Georgian breakaways South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent enclaves.

Some analysts believe that Lukashenko will not be able to keep balancing these relationships anymore, as Europe will not accept him as a dialogue partner, given the circumstances of the last few months and the clear gap in understanding between him and Western leaders.

Analysts from the Carnegie Center say that from Lukashenko’s standpoint, he never promised “free” elections. Lukashenko only promised to allow presidential candidates to speak out during the pre-election campaign in return for economic assistance from the EU and guidance from the Organization for Security and Co-operation (OSCE).

The day following the crackdown on protesters, Lukashenko gave a press conference declaring “there will be no dull democracy in the country,” showing his continuing stranglehold on the country.

“We will no longer try to please anybody. We did that to find an easier and better way to normalize relationships with the European Union and the United States,” he said at that time.

Lukashenko ended the OSCE’s mandate in Belarus late last year after the organization’s observers strongly criticized the elections outcome.

Belarus’ president sent a similar message after the coup in Kyrgyzstan last April, saying that he would not allow the same thing to happen in his country.

By straining relations with both the East and West, Lukashenko has “caught himself in a trap and he either is not noticing that or he has understood it and is behaving like a ‘wounded animal,’ fighting for his survival,” said Stephan Malerius, a representative of the German foundation Konrad Adenauer, from its office for Belarus based in Vilnius, Lithuania.

Belarus’ ties with the White House have been repeatedly tested since the early years, with Minsk confiscating the U.S. ambassador’s house at one point, and expelling American diplomats at another.

If Lukashenko wants normalized relations with the West, he will have to comply with demands to allow investigations into election fraud and the crackdown, and will have to release jailed opposition politicians, journalists, and others.

Belarus has long since been under authoritarian control, first under the Soviet Union, then under Lukashenko since the first post-Soviet elections in 1994, with no experience of democracy or input to a political process. This makes the prospects for democracy a dim dream, according to some hopefuls.

“Our people are very passive to organize. They don’t know what to do, how to protect their [opposition] leaders. We can see what happened in the last elections. People just are not ready,” wrote Ekaterina Pavlova, 30, who lives in the western town of Hrodna.

“So there is no decent opposition, neither are there chances for its existence. But people disagree inside.”

“It [the opposition] exists for the sake of appearance. Everything is controlled. Generally speaking, there was nobody to vote for in the elections,” she wrote.

“There is no movement here. If something shows up, leaders disappear somewhere very quickly,” she added.

According to Pavlova, nobody talks about what is happening to opposition politicians in the country, with everyone pretending that everything is fine.

Before the December vote, opposition candidates were allowed to voice different platforms and let people know about alternatives. Some television programs critical of Belarus’ heavy-handed President Alexander Lukashenko were aired, broadcast via Russian channels, which have a solid market share in the country.

The West and East were split over reactions to the election and its fallout. Western governments strongly condemned the vote as fraudulent and criticized Lukashenko for the violent crackdown on demonstrators.

On Dec. 23, 2010, days after the crackdown and arrest of over 600 demonstrators, opposition politicians, and journalists, the United States and European Union issued a joint statement strongly condemning the violence.

“Taken together, the elections and their aftermath represent an unfortunate step backwards in the development of democratic governance and respect for human rights in Belarus. The people of Belarus deserve better,” read the statement.

From the East, Russia and other former Soviet countries deemed the elections fair and in keeping with international standards, and that anything else was a domestic affair.

Most of the presidential candidates, journalists, and human rights activists ended up being taken into custody were accused of violating social order, and will face trial at the end of this month.

Media controlled from the capital, Minsk, bluntly accused the European Union last week, particularly German and Polish intelligence services, of being behind the election day demonstrations.

The West, meanwhile, is considering its position on imposing sanctions on top Belarusian officials. On Jan. 31, EU foreign ministers will meet to discuss its policy toward Minsk.

“It will unfortunately have to be discussed again whether we’ll have to revive sanctions that we really should have put behind us. It’s very regrettable,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel said on Jan. 14 in Berlin after a meeting with her Italian counterpart PM Silvio Berlusconi, who also supported stricter approaches toward Belarus.

“The looming question for Western leaders is whether to revive tough sanctions and close the door on engagement with the Lukashenko regime, or to seek a solution that will undo the direct post-election abuses while leaving open the possibility of future re-engagement,” the Carnegie Endowment, the global think tank, said in its recent analysis on the issue.

In 2006, Washington and the EU imposed travel and trade sanctions on Belarus following rigged presidential elections that were also accompanied by the arrest of opposition politicians. After a thaw, the sanctions were lifted two years later, with the EU taking a new policy direction of engagement, not isolation.

In 2008, Belarus was invited to participate in the EU Eastern Partnership project particularly aimed at Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine to bring the post-Soviet countries closer to the EU, and help promote democratic norms there.

This time, too, the EU has expressed that further isolation of Belarus will not bring hope for reforms and benefits for ordinary Belarusian citizens and would only serve to push the country closer to the Kremlin.

“While we express our concern to the authorities, we cannot isolate the citizens,” said Catherine Ashton, EU high representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, in a letter addressed to the European Council President Herman Van Rompuy on Jan. 19.

For the last decade, Lukashenko has also tried to balance its ties with the West and East. Minsk relies heavily on the East as a market for Belarusian-made products given customs and trade benefits mainly with Russia and Kazakhstan.

However, the last year has been a rocky one in Belarus-Russia relations, filled with political opposition, wars of words, and gas price disputes. The Kremlin has expressed its annoyance with Lukashenko for not satisfying Russian interests; for example, Belarus refuses to recognize disputed Georgian breakaways South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent enclaves.

Some analysts believe that Lukashenko will not be able to keep balancing these relationships anymore, as Europe will not accept him as a dialogue partner, given the circumstances of the last few months and the clear gap in understanding between him and Western leaders.

Analysts from the Carnegie Center say that from Lukashenko’s standpoint, he never promised “free” elections. Lukashenko only promised to allow presidential candidates to speak out during the pre-election campaign in return for economic assistance from the EU and guidance from the Organization for Security and Co-operation (OSCE).

The day following the crackdown on protesters, Lukashenko gave a press conference declaring “there will be no dull democracy in the country,” showing his continuing stranglehold on the country.

“We will no longer try to please anybody. We did that to find an easier and better way to normalize relationships with the European Union and the United States,” he said at that time.

Lukashenko ended the OSCE’s mandate in Belarus late last year after the organization’s observers strongly criticized the elections outcome.

Belarus’ president sent a similar message after the coup in Kyrgyzstan last April, saying that he would not allow the same thing to happen in his country.

By straining relations with both the East and West, Lukashenko has “caught himself in a trap and he either is not noticing that or he has understood it and is behaving like a ‘wounded animal,’ fighting for his survival,” said Stephan Malerius, a representative of the German foundation Konrad Adenauer, from its office for Belarus based in Vilnius, Lithuania.

Belarus’ ties with the White House have been repeatedly tested since the early years, with Minsk confiscating the U.S. ambassador’s house at one point, and expelling American diplomats at another.

If Lukashenko wants normalized relations with the West, he will have to comply with demands to allow investigations into election fraud and the crackdown, and will have to release jailed opposition politicians, journalists, and others.

Belarus has long since been under authoritarian control, first under the Soviet Union, then under Lukashenko since the first post-Soviet elections in 1994, with no experience of democracy or input to a political process. This makes the prospects for democracy a dim dream, according to some hopefuls.

“Our people are very passive to organize. They don’t know what to do, how to protect their [opposition] leaders. We can see what happened in the last elections. People just are not ready,” wrote Ekaterina Pavlova, 30, who lives in the western town of Hrodna.

“So there is no decent opposition, neither are there chances for its existence. But people disagree inside.”

“It [the opposition] exists for the sake of appearance. Everything is controlled. Generally speaking, there was nobody to vote for in the elections,” she wrote.

“There is no movement here. If something shows up, leaders disappear somewhere very quickly,” she added.

According to Pavlova, nobody talks about what is happening to opposition politicians in the country, with everyone pretending that everything is fine.