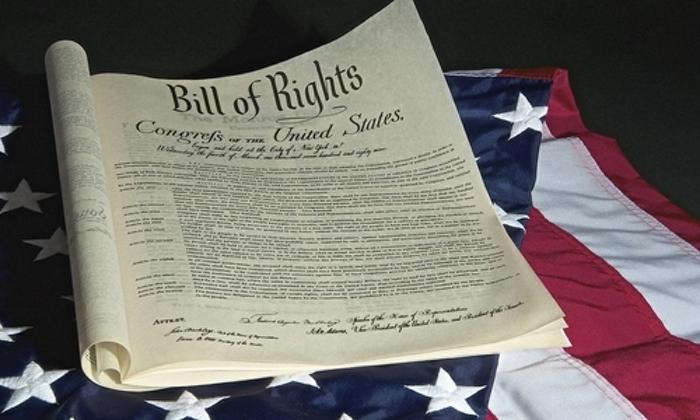

In honor of U.S. Constitution Day, on Sept. 17, we present a five-part series on the Bill of Rights. It reveals how the first 10 amendments to the Constitution guarantee freedom of speech, religion, and the press, and, in so many other ways, limit the power of the federal government and secure the rights of individuals.

Congressman James Madison, who co-authored the “The Federalist” papers along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, played an important role in drafting the U.S. Constitution at the 1787 constitutional convention in Philadelphia. He also worked for its subsequent ratification. In 1791, he penned what would become the American Bill of Rights.