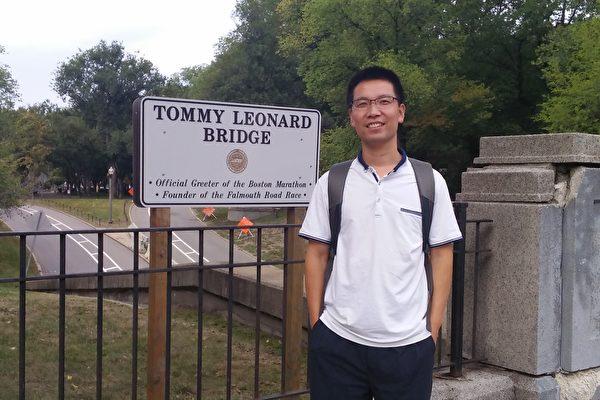

Li Baoyang, a researcher at one of China’s most prestigious universities, breathed a sigh of relief when he reached the United States on Nov. 5. He had been hounded by the authorities for his online postings in a 20-day sweep that has shut down over 9,800 blogging accounts.

The scale and duration of the action were announced on Nov. 12 by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Cyberspace Affairs Commission (CAC), which policies China’s internet.

Speaking to The Epoch Times in an exclusive interview, Li said that when he was in China, he thought he had a bright future to look forward to. This June, Li graduated with a Ph.D degree in Chinese language and literature at Sun Yat-sen University, which is located in Guangzhou, southern China, and ranks in the top 10 Chinese universities. The next month, he received a research position at the school’s Information Management Institute.

But Li’s faith would present him with unforeseen challenges. A Christian, he didn’t trust the Communist Party-controlled Three-Self Patriotic church organization, created to bring Chinese Protestants under the regime’s oversight.

On Aug. 18, Li made a post visible to a circle of friends on WeChat expressing his mood about changes in the religious environment.

“A sister just told me that she didn’t go to church since [the beginning of] August because the church was forced to fly the five-star red flag [the national flag of communist China]!” Li wrote. “I remember that last year, I went to church with my kids, but saw a short-haired middle-age woman at the pulpit preaching socialist core values. After that, I don’t take my children there any more.”

The next month, on Sept. 14, a research advisor called Li over for a talk about his WeChat post. Two days later, he received a warning from the Party secretary telling him to stop improper posting on WeChat and other social media, such as the Twitter-like Weibo.

When Li asked how to determine what was an “improper” post, the secretary avoided the question and said: “if you insist on expressing these sorts of views, no university or institute will give you work.”

After this conversation, Li’s political background credentials were suspended by the university.

At the end of the month, the Information Management Institute held a staff meeting. But the night before the event, Li’s advisor called, instructing him to call the Party secretary and ask to resign.

The advisor threatened Li, saying that if he didn’t resign, the Institute would add his politically incorrect views to his official background records — which would make it virtually impossible for him to ever find another job. Li was unable to reach the CCP secretary before the meeting.

“My advisor talked with me several times, criticizing me in a way that I had never seen of him for the last 17 years,” Li Baoyang said. “I felt a deep injustice was done to me, because all I did was speak my conscience and speak as someone with a sense of morality. Many friends told me that I said what they had in their minds, but didn’t dare express in words.”

Afterward, Li’s circumstances quickly worsened.

In the night of Oct. 26, two unfamiliar men went to Li’s home. After entering, one of the men pinned him to his bed, while the other ransacked his room, demanding his cell phone and notebook computer.

After searching the house, they took Li away to interrogate him in a tiny chamber. A bright lamp was shown in his face. The men checked his phone and demanded answers.

“I was very scared. I had never experienced anything like this,” Li said. “I was just a scholar and an instructor. I was a deer in the headlights, I had no idea how to deal with the situation in front of me.”

“They didn’t tell me which department they are working for, national security or public security,” Li said. But “it was clear that they knew my background.”

In 2012, when he worked for Zhejiang University, Li’s wife became pregnant with a second child, then illegal under the Chinese regime’s one-child policy. Li was forced to resign, and their child had not been allowed to register for the official status that is needed for public education and other forms of social participation.

The agents also knew that three years ago, Li had taken part in a parade to commemorate a pro-democracy activist.

The next morning, Li was dropped off on the side of a street. He found that the photos on his phone had been deleted. A former classmate of his, employed in the regime’s security forces, notified him that he was placed on a list of politically sensitive individuals. For Li’s safety, the friend urged him to leave China.

A week later, Li got on a plane in Shanghai and departed for the United States.

Li Baoyang is one of the most recent examples of an ordinary Chinese citizen suffering persecution for his online expression of faith and political opinion.

Among the social media accounts deleted en masses by the Cyberspace Affairs Commission (CAC) were prominent users with tens of millions of followers.

After the CAC made its announcement on Nov. 12, WeChat and Weibo said that they had closed more than 200,000 accounts suspected of spreading “improper” information and fake news.

WeChat is operated by Tencent, the world’s largest gaming and social media company, and one of the biggest technology conglomerates in China. Sina, which runs Weibo, is one of China’s four major web portals with over 600 million users worldwide. Weibo has over 500 million users.

A commentary by the state-run CCTV listed “six major crimes” associated with social media — vulgar and pornographic content, clickbait, spreading rumors, fraudulent public relations, buying clicks, and plagiarized content.”

The Party-controlled People’s Daily ran similar commentaries. But in recent years, netizens have been turned off by the CCP’s heavy-handed measures.

“Different types of user-generated media, especially those concerning current affairs, have become powerful weapons for enlightening the Chinese,” Yuan said. “They represent a strong push against the CCP’s authoritarian system.”