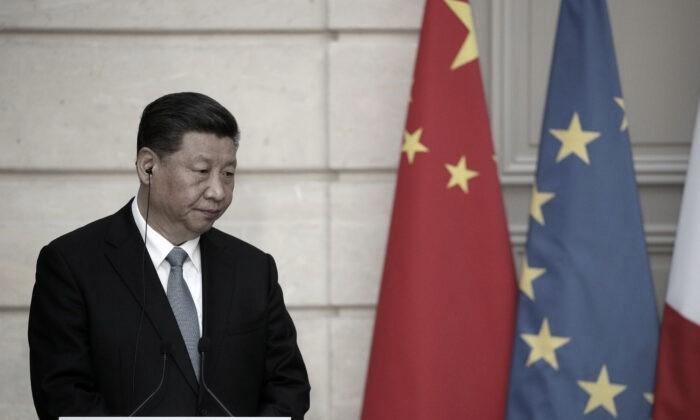

China hinted that its carbon reduction initiatives would now move at a cautious pace, after the communist regime’s leader Xi Jinping said that carbon-cutting goals should not come at the expense of the “normal life” of ordinary people.

His words come at a time when Beijing has continued to produce coal at a record pace, while experts are questioning whether the Chinese regime could actually fulfill its goals of achieving carbon peak before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, promises made by Xi in September 2020.