China’s Continuous Cyberthreat to the US

That puts China’s state-sponsored cyberattacks against the United States in a much more critical and dangerous light.How do we know that China’s repeated cyberattacks against critical U.S. defense agencies, technology, financial, and other strategic sites aren’t done so with kinetic war as the follow-up?

With tensions rising, suspicion levels rise, as well they should. It’s no secret that Beijing views the United States as its top adversary.

Is it time to consider the Chinese regime’s ongoing cyberattacks against U.S. agencies, including the theft of strategically valuable and sensitive data, to be an act of war?

If not, why not?

Attribution Challenges

For one, the truth is a bit more complex. Not every cyberattack can be traced back to its perpetrator. Others use attribution deception to deflect blame. Plus, many cyberattacks come from very sophisticated hackers that are not sponsored by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) or Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia, Belarus, or elsewhere.Besides, Beijing can argue that those who hack into many of the same systems do it just for the money.

That’s undoubtedly true.

It’s well known that hackers attack all kinds of sites, particularly high-value targets such as medical institutions, financial institutions, and government agencies. Once a network penetration is successful, hackers can plant a code that prevents the victims’ access to their data unless they pay a fee or ransom. As they are known, ransomware attacks are one of the most common kinds of cyberattacks worldwide.

The Attribution Escalation Calculus

Attribution is not always possible, but it can also have an escalatory effect—and China knows this. Once an accusation is made, the pressure for a punitive response by the accuser grows, doesn’t it?US Makes Exploitation Easy

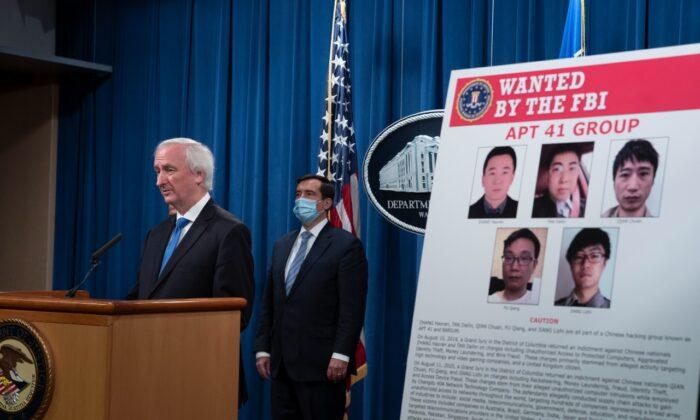

What’s more, in some cases, the United States has made it easy for adversaries to gain access to some of the most sensitive U.S. sites. The group APT41, for example, is used by the CCP to quickly exploit software flaws and security vulnerabilities that were made public by U.S. researchers.In other words, the United States showed the CCP how to hack some of its systems.

Even after the APT41 was detected, it has easily adapted to defense measures in order to repeatedly exploit publicly known vulnerabilities.

Who’s to blame for such stupidity? Are the Chinese at fault for taking advantage of us even as we make it so easy?

The Stuxnet Dilemma: From Cyberwarfare to Kinetic Warfare

Nonetheless, state-sponsored hackers often do more than steal intellectual property (for example, industrial espionage). Other times, they’re testing their ability to penetrate and monitor critical government systems from defense to financial interests and beyond.These activities in the digital world can easily result in kinetic warfare in the physical world. The Stuxnet cyberattack caused physical damage to machinery that an airstrike would typically destroy.

The China Offensive Is Here

No nation has dedicated more resources to cyberwarfare than the Chinese regime—and for a good reason. Intellectual property theft is a critical component in its drive for technological, economic, and military supremacy. Ongoing cyberattacks and data theft are significant parts of the CCP’s long-term plan.Indeed not a good sign for the future of U.S.–Sino relations.