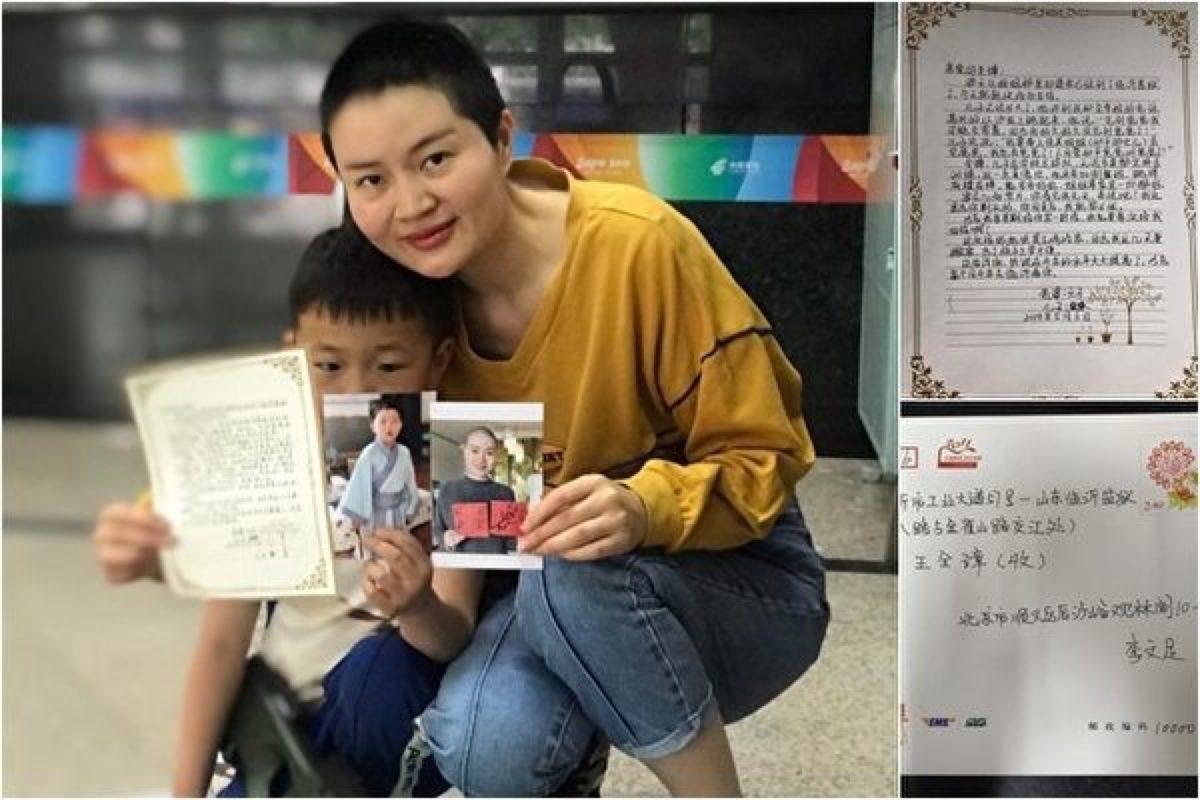

Years of tireless effort seemed to have finally brought the first glimmer of hope to the wife of jailed human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang. Li Wenzu tweeted on June 26 the police had granted her husband a family visit, scheduled for June 28.

Their 6-year-old son is looking forward to their visit, and wants to ask his father about the meals he’s been given in prison.

“Linyi Prison has finally set a date for the meeting: At 8:24 this morning, Linyi Prison told me in a call that I can meet with Wang Quanzhang on June 28 at 2:00 pm!” Li wrote in a June 26 tweet.

Wang was a prominent figure in the human rights community for his work in defending the oppressed groups in China—farmers whose houses were forcibly demolished when the Chinese regime seized their lands; Christians who are hiding underground; and adherents of the persecuted spiritual discipline Falun Gong.

Voice Outside the Prison Wall

Li said her original wish was to live a peaceful life with her husband and raise their child, she told the Vision Times in an interview on September 2018. But the detention of her husband had disturbed that world and encouraged her to step out for other people.“You don’t have the right to choose the life you want ….The more I learn about what he has done, the more I feel that I should do things for him. He did it for others and ignored his safety, and I now stand up for my husband to rescue him.”

Over the past few years, Li and several other wives of jailed human rights lawyers have become a regular sight in front of the Tianjin Detention Center, and later, Linyi Prison in Shandong Province, where Wang was recently transferred.

The women used creative props, held up banners and called out Wang’s name to show their support for the imprisoned lawyer, and demanded the guards to let them visit him.

One time in 2016, Li and a few others held red plastic buckets inscribed with the Chinese characters “Quanzhang, [we] have faith in you, [we’re] waiting for you.” They were arrested for disturbing the public order.

Since Wang’s arrest, authorities have threatened, harassed, and monitored Li. Despite the police intimidation, she has kept up her spirits, and took to social media to document and share the moments of her journey. By doing so, Li said she was sending a message to the authorities.

“We decided that if we would go to the detention center in the future, we should dress nicely and take pictures frequently,” Li told the Vision Times. “We wanted to tell them that we wives have not been scared away and have not given in—we are proud of our husbands.”

Support

Wang’s case has drawn attention from international human rights groups, bar associations, and government officials.“The attention that Mrs. Li Wenzu and the other wives have brought, not only to their husbands’ plight, but also to the state of the crackdown, is a wonderful example of courageous human rights activism,” said Caroline Edelstam, the director of the Sweden-based international monetary fund, commending Li’s “untraditional” and “instrumental” methods to defend human rights.

“Wang was among the first individuals detained during the Chinese government’s July 9, 2015 (“709”) crackdown on legal advocates for rule of law and human rights defenders, and the last to be tried,” said Robert J. Palladino, the State Department’s deputy spokesperson.