After interviewing Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai, a French reporter with sports newspaper L’Equipe said on Tuesday the restrictive interview was likely part of a propaganda effort by the Chinese regime.

The L’Equipe interview with the three-time Olympian and former top-ranked doubles player was organized and watched over by Chinese officials in a hotel in Beijing on Sunday. It was published on Monday.

In the interview, Peng denied having accused Zhang of sexual assault and claimed that she deleted the allegation from social media herself.

“This post resulted in an enormous misunderstanding from the outside world,” Peng said in the L’Equipe interview. “My wish is that the meaning of this post no longer be skewed.”

A day after the interview, Ventouillac said he remained unsure if Peng was free to say and do what she wants. “It’s impossible to say,” he told The Associated Press in English. “This interview don’t [sic] give proof that there is no problem with Peng Shuai.”

Ventouillac said he believed Chinese officials granted the interview so Peng’s situation did not divert attention away from the Beijing Winter Olympics.

“It’s a part of communication, propaganda, from the Chinese Olympic Committee,” he said.

During the interview, Peng didn’t directly answer a question about whether she had been in trouble with the authorities after making the allegation. Instead, she echoed state talking points.

“I was to say first of all that emotions, sport, and politics are three clearly separate things. My romantic problems, my private life, should not be mixed with sport and politics,” she said.

Questions in Advance

Wang Kan, chief of staff of the Chinese Olympic Committee (COC), sat in the interview and translated Peng’s answer from Chinese to English. To verify the accuracy of the translation, L’Equipe used a separate interpreter in Paris to translate Peng’s answer into French.Ventouillac said L’Equipe sent questions in advance and could only publish Peng’s responses verbatim in Question & Answer format, which the COC requested. The COC also allotted half an hour for the interview.

But Ventouillac and his colleague had a chance to ask more questions than they submitted prior to the interview which lasted about one hour.

“She answered our questions without hesitating—with, I imagine, answers that she knew. She knew what she was going to say,“ Ventouillac said. ”But you can’t know whether it was formatted or something. She said what we expected her to say.”

Ventouillac asked questions relating to both tennis and Peng’s sexual assault allegation. When answering questions relating to the latter, Peng seemed more nervous and careful, Ventouillac said, adding that she “seems to be healthy.”

Ventouillac said that he believes that international support will protect Peng because Chinese people not so well-known outside China would be in jail for making such an allegation against a senior official.

‘Staged Interview’

Laura Harth, campaign director at Safeguard Defenders, is among those questioning the integrity of Peng’s interview based on the way it is conducted and its timing.“Again, with full respect of the person, we do not find [Peng’s comments] very credible … She was not alone, her questions had to be submitted in advance, and the answers were also reviewed in advance [of publishing]," Harth told The Epoch Times on Tuesday.

“L'Equipe did not have the possibility, actually, to have a frank and open conversation with her,” she said.

Peng’s language also paralleled the narrative of the Chinese authorities, Harth said.

“It’s quite unnatural for a person, I would say, when she’s asked about her personal life over the past months, to only refer to perfectly staged moments that we have seen through the Chinese propaganda machine,” she said.

Harth said she suspects Peng’s case falls within the paradigm of how the CCP forces confessions from those involved in “politically sensitive” matters.

“Over the past years, since 2013, we’ve seen the number of enforced disappearances going up: the number of human rights defenders, journalists, citizen journalists, human rights lawyers, everyone who tries to portray a different voice… being locked up, being disappeared for a period of time, and then maybe coming back, either in state media are in trials with these kinds of scripted and forced confessions,” Harth said.

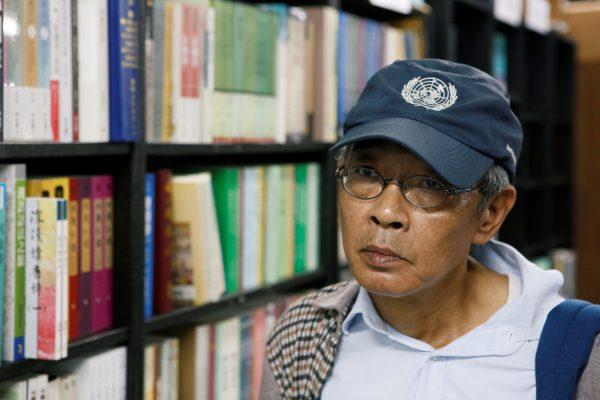

A prime example of this draconian measure is what happened to several Hong Kongers selling books critical of Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

Among them was Lam Wing-kee who was seized in the Chinese city of Shenzhen in October 2015. He later said he was forced by Chinese agents to give a false confession that was broadcast on Chinese television.

Exporting Terror

The CCP’s repression campaign is not limited to those within China, said Harth.“[The involuntary returns] highlights how what is happening inside China is no longer just happening inside China,” she said.

“We are increasingly seeing how the CCP is successfully exporting its regime of political terror of fear around the world by threatening and menacing people all around the world, by having them return to China for persecution, or for disappearance, torture.”

Those enabling the Chinese regime, Harth added, are bodies like the International Olympics Committee (IOC).

“The IOC always came to the rescue of the CCP at the exact right moment,” she said.