NEW YORK—Mayor Michael Bloomberg is hailed by many in the public health sector as a visionary who isn’t afraid to try out new things.

The large sugary drink ban, blocked by a judge on Monday, is only the latest in a series of public health initiatives Bloomberg has developed. Despite the setback, many of the mayor’s signature efforts have received fairly widespread support.

Beginning in 2002 with banning smoking from most buildings—including bars—a controversial and relatively trend-setting move at the time, Bloomberg has moved on to nutrition and exercise programs for children, and regulating the consumption of sugary drinks.

Two of Bloomberg’s most famous health initiatives started in 2007 with a ban on trans fat, which naturally occurs in small amounts in meat and dairy products, but a health risk when coming from partially hydrogenated oil that turns solid at room temperature. Next, the city began requiring chain restaurants to post calorie counts on menus— a measure that was included in the federal Affordable Care Act.

Later, several initiatives failed to pass into law—such as not letting people buy sugary drinks with food stamps.

“I just give Bloomberg a lot of credit for trying these things,” said David Levitsky, professor in the Division of Nutritional Sciences at Cornell University. “That’s more than any other mayor in any other town is doing—or any other public official—and I think we have to try these things.”

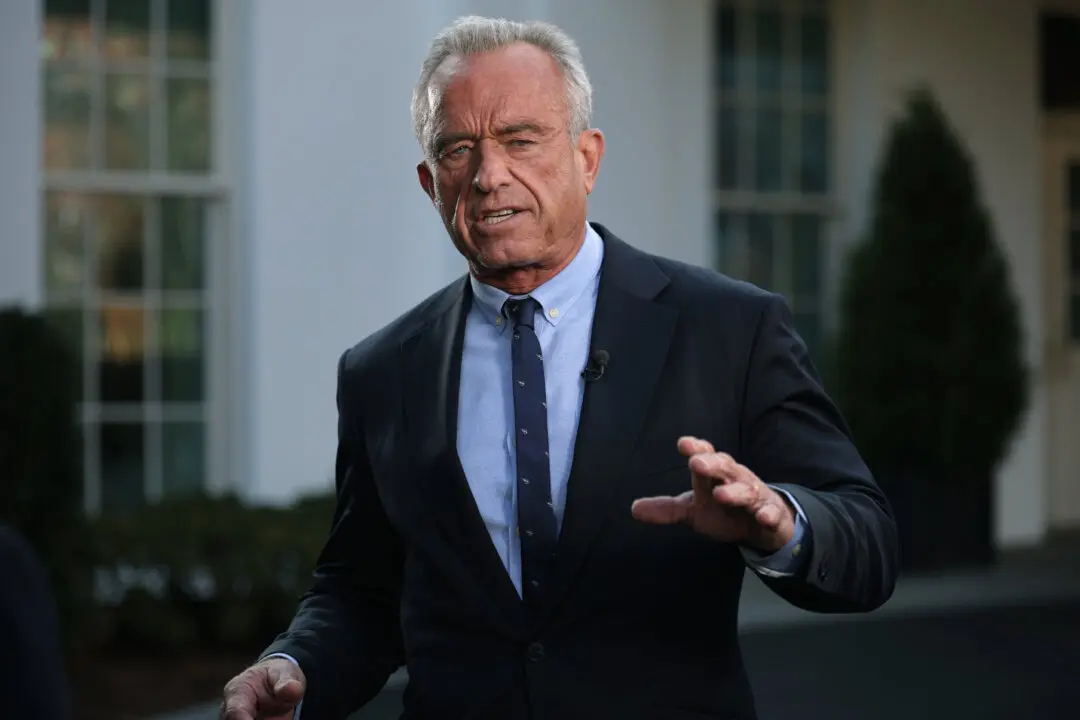

(Diana Benedetti/The Epoch Times)

Do Initiatives Equal Success?

Levitsky, along with some others in the public health field, credit Bloomberg with using solid data to craft his initiatives, but they question their effectiveness and ability to deliver substantial results.

Sugary drinks lead to increased body weight, but whether reducing container size would result in people consuming fewer calories and losing weight is questionable, said Levitsky. The large sugary drink ban would have banned most drinks larger than 16 ounces containing more than 50 calories.

If the ban had passed, “it would have been a perfect laboratory to study if indeed that is possible,” he added.

There are two approaches to public health. The first is dealing with things at a mass level, such as creating a law to limit certain behaviors or launching an advertising campaign. The second involves a more personal approach, where the tools are emphasized more, such as encouraging the use of regular monitoring of a person’s weight using scales. Bloomberg prefers the former.

Those who support and advocate Bloomberg’s methods frequently cite his successes, such as New Yorkers’ longer life expectancy, and a 5.5 percent reduction in children’s body mass index (how much fat people have) between 2006 and 2011, which the administration attributes to its aggressive nutrition and exercise programs.

“Clearly the public health regulations are having some kind of impact,” said Jennifer Pomeranz, director of Legal Initiatives at Yale University’s Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. “And I think that New York City’s totally been an innovator in terms of food policy.”

Out of all of Bloomberg’s initiatives, the trans fat ban and menu labeling stand out. Philadelphia, Boston, and the state of California have adopted one or both measures after New York City, and the federal government also included menu labeling in the Affordable Care Act.

“The effect has certainly been to start a national conversation, which I think is one of the most important roles that New York City has ended up playing,” said Pomeranz, who worked with the city on the menu labeling, and has written in support of the large sugary drink ban.

Pomeranz said she believes the ban on sugary drinks is completely legal, considering the Department of Health is charged with addressing chronic disease and food supply.

The judge who ruled it is outside the city’s jurisdiction to enact the ban “is basically confining the department to address things like sanitation problems, which are health issues that are long gone as being the most pressing public health issues of our day,” she said.

Bloomberg ‘Grasping’ for Soda Initiative

While the large sugary drink ban struck many, including the judge, as arbitrary, it is just the latest proposal attempting to get people to drink less soda and other sugary drinks.

In early 2010 Bloomberg urged the state Legislature to pass a tax on soda. The penny-per-ounce tax was intended to help fight obesity through an estimated $1 billion, which would have been earmarked for education and Medicaid. It didn’t pass.

Soon after, Bloomberg and then-Gov. David Paterson proposed a pilot program to block people from using food stamps to buy sugary drinks. The federal government rejected it, citing a number of concerns related to enforcement and effectiveness in combating obesity.

Both of these proposals would have been effective if passed, according to Dariush Mozaffarian, associate professor in the Department of Epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Now, Bloomberg is “grasping to find anything he can do” to limit sugary drinks, because his two main proposals were blocked, said Mozaffarian. He added that in his view no other states would be willing to try proposing a similar pilot program for food stamps unless the Obama administration signals its support.

“The food stamp program says in its mission statement that the goal is to provide healthy and nutritious food for people who can’t afford it, so it’s just outrageous that we should be using that to buy sugar sweetened beverages,” said Mozaffarian.

“It’s amazing to me the way the government is not just taking the sensible approaches that would reduce cost, make a healthier food supply for everybody, and make everybody actually feel better,” he added. “So I think that Mayor Bloomberg is a great example of what politicians should be trying to do.”