NEW YORK—Against a backdrop of crumbling towns and failing schools, Puerto Ricans on Sunday will cast votes on whether their struggling island should become the 51st state.

The status referendum, Puerto Rico’s fifth since 1967, is unlikely to change the island’s label as a U.S. territory, a move that would require an act of the Congress.

But the vote is culturally important and timely for an island whose hazy political status has contributed to an economic crisis that pushed it last month into the biggest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history.

Sunday’s plebiscite will offer voters three options for Puerto Rico: to become a U.S. state; to remain a territory; or to become an independent nation, with or without some continuing political association with the U.S.

Congressional apathy “doesn’t mean the vote’s not worth doing, because this kind of vote is the only way out of a colonial situation,” said Columbia Law School Professor Christina Duffy Ponsa, an expert on Puerto Rico territory issues who supports statehood.

Hamstrung by $70 billion in debt and a 45-percent poverty rate, Puerto Rico is battling woefully underperforming schools, and near-insolvent pension and health systems.

Its 3.5 million American citizens do not pay federal taxes, vote for U.S. presidents or receive proportionate federal funding on programs like Medicaid.

Best Hope

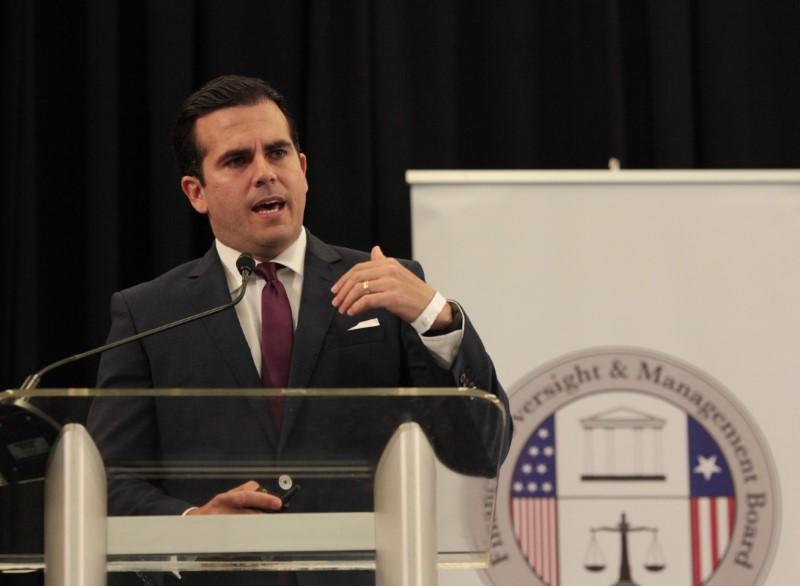

Governor Ricardo Rossello campaigned on holding a referendum and believes U.S. statehood is the island’s best hope. His PNP party, which controls Puerto Rico’s government, is premised on a pro-statehood stance. The opposition PPD supports versions of the current territory status.

Ramon Rosario Cortes, a Rossello spokesman, told Reuters the governor will push Congress to respect the result, “and we expect they will respect the will of 3.5 million American citizens.”

But Puerto Rico is seen as a low priority in Washington and “Congress won’t do anything,” said U.S. Rep. Luis Gutierrez, an Illinois Democrat of Puerto Rican descent, who supports making the island an independent nation.

“It’s not that we’re ignoring the plebiscite; we’re ignoring the plight of Puerto Ricans,” he said.