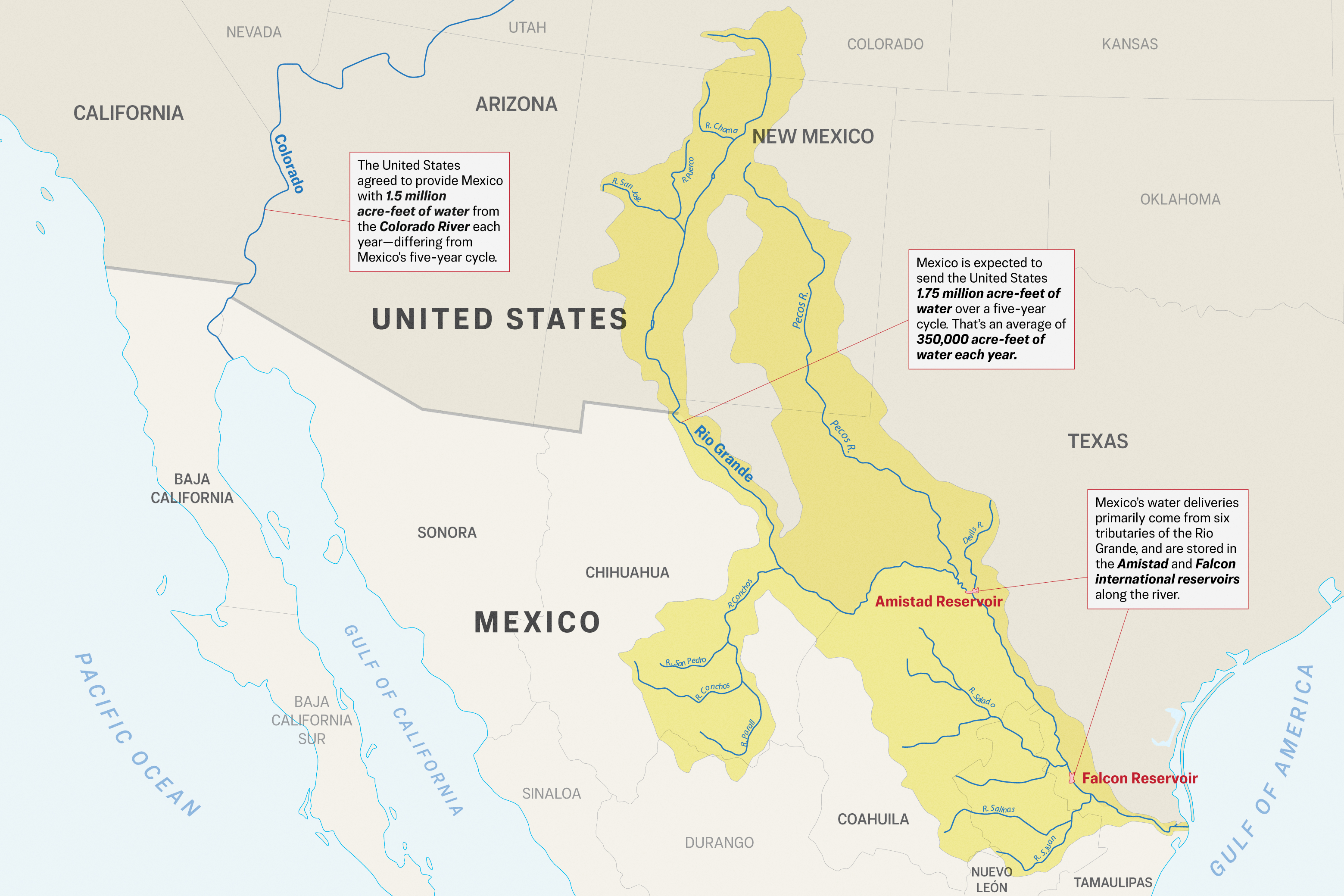

Mexico’s delinquent water deliveries, in violation of an 81-year-old treaty with the United States, have exposed years of “blind eye” policies, rapid population growth, and hydrological changes, according to an expert at the U.S. Army War College.

Evan Ellis, research professor of Latin American studies at the college’s Strategic Studies Institute, told The Epoch Times that recent tensions over Mexico’s delinquent water deliveries have come from “years of looking the other way” on the part of the United States.