Sitting in for a meeting of China’s top political advisory body was a badge of honor for Wang Haijun.

Even with South Korean police probing his restaurant as a likely Chinese spy base, Mr. Wang, a Chinese national, has remained a valuable asset for Beijing: decorated and politically connected, ready to advocate for the communist cause, eager to contribute to local Chinese embassy activities; he has served as an overseer of a half-dozen Chinese front groups, and the host to more than 100 visiting Chinese groups each year.

In a country that fought a bloody war to fend off a communist takeover 70 years ago, the extensive political fingerprint from people such as Mr. Wang appear to critics as emblematic of a silent form of invasion, even before South Koreans—and the world—have come to grasp what’s happening.

“Korea is a war zone without gunfire,” the former head of a Chinese–Korean association, who has sources close to the Chinese embassy in Korea, told The Epoch Times on the condition that he be identified by only his first name, Harry.

By his assessment, the CCP over the years has penetrated 80 percent of South Korean politics and society, on a trajectory that recently came to a halt with a change of leadership that’s steering South Korea out of Beijing’s orbit.

High Stakes

Despite a public opinion poll in 2022 indicating that South Koreans have the world’s most negative view of communist China, the nation came dangerously close to choosing a socialist track.That March, Yoon Suk-yeol, who promised to align his country closer to the United States and away from Beijing, won the presidential election on a razor-thin margin of less than 1 percent. His opponent was current opposition leader Lee Jae-myung, who held nearly 48 percent of the popular vote and once said he aspired to be a “successful Bernie Sanders.”

“That was the closest election in South Korean presidential history,” Suzanne Scholte, president of Virginia-based Defense Forum Foundation, told The Epoch Times.

“It’s a very serious problem that we need to be aware of,” said Ms. Scholte, who has received the Seoul Peace Prize for her advocacy for North Korean human rights. “A liberal democracy like South Korea almost elected a pro-communist candidate in the last election.”

The stakes for South Korea’s future also hold significance for the United States.

“The CCP should not be underestimated,” Han Minho, former director general of South Korea’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, and well-versed in the Chinese regime’s infiltration tactics, told The Epoch Times.

“They want to take down the United States and rule the world.”

The issue with the rising anti-Beijing sentiment is that it “doesn’t come from a deep understanding of the CCP, but is often an immediate reaction to unreasonable demands on South Korea, such as the wolf warrior diplomacy,” he said, referring to the combative posture that Chinese diplomats have adopted in recent years.

“We need to have a deeper understanding that this [the CCP] is the worst mafia in human history that has internalized all the wisdom that has been accumulated over the past 2,500 years, and it uses all kinds of tricks that we can’t imagine,” Mr. Han said.

‘Our Loyalty Is to China’

The “best way” for the CCP to defeat the United States, according to Cho Hyeon-gyu, a retired army colonel and former military attaché at the Korean Embassy in China, is to disrupt its alliances—the core of which in Asia is South Korea.In its attempts to “immobilize” South Korea, the Chinese regime attacks like a “trident,” in three ways: Make South Korea economically dependent on China, win the upper echelons of society to their side, then create a pro-China climate among the general public, Mr. Han said.

The strategy is colloquially known as the United Front, and what Party founder Mao Zedong dubbed a “magic weapon.”

It became a lifeline to the Chinese communists during the Party’s early years. When it was struggling to survive against a far more powerful domestic opponent, the Nationalist Party, it latched onto the adversary until it was weak enough to be defeated.

Once again—this time in South Korea—the strategy has succeeded, Mr. Han said.

In his first state visit to Beijing in 2017, then-Korean President Moon Jae-in praised China as a “high mountain peak” whose dream of a “small country” such as his own will happily embrace.

Two years before that, Park Geun-hye was the only leader of the democratic country to climb atop the Tiananmen Tower, standing shoulder to shoulder with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Xi, to watch Beijing’s massive World War II parade.

In 2022, a visit from Li Zhanshu, then-head of China’s rubber-stamp legislature, led to the creation of a parliamentary fraternity group—the South Korea–China Parliamentarians’ Union, with one-third of the 300 Korean National Assembly members joining to facilitate legislative exchange.

Such collaboration struck Harry as an outrage.

“Frankly, it doesn’t make sense to me that officials from a communist country and lawmakers from a free country should be working together on legislation,” he said.

In 2019, a present to then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) captured well the political sentiment that prevails in South Korea, Myongji University professor Kahng Gyoo-hyoung said.

During his visit to the United States, then-Korean National Assembly Speaker Moon Hee-sang gifted a handwritten scroll to Ms. Pelosi on which he wrote “All rivers flow east,” an ancient Chinese proverb that has a historic undertone of placating China.

Mr. Kahng, who currently chairs the country’s National Archives Management Committee, chuckled as he recalled the scene.

Gaining Ground

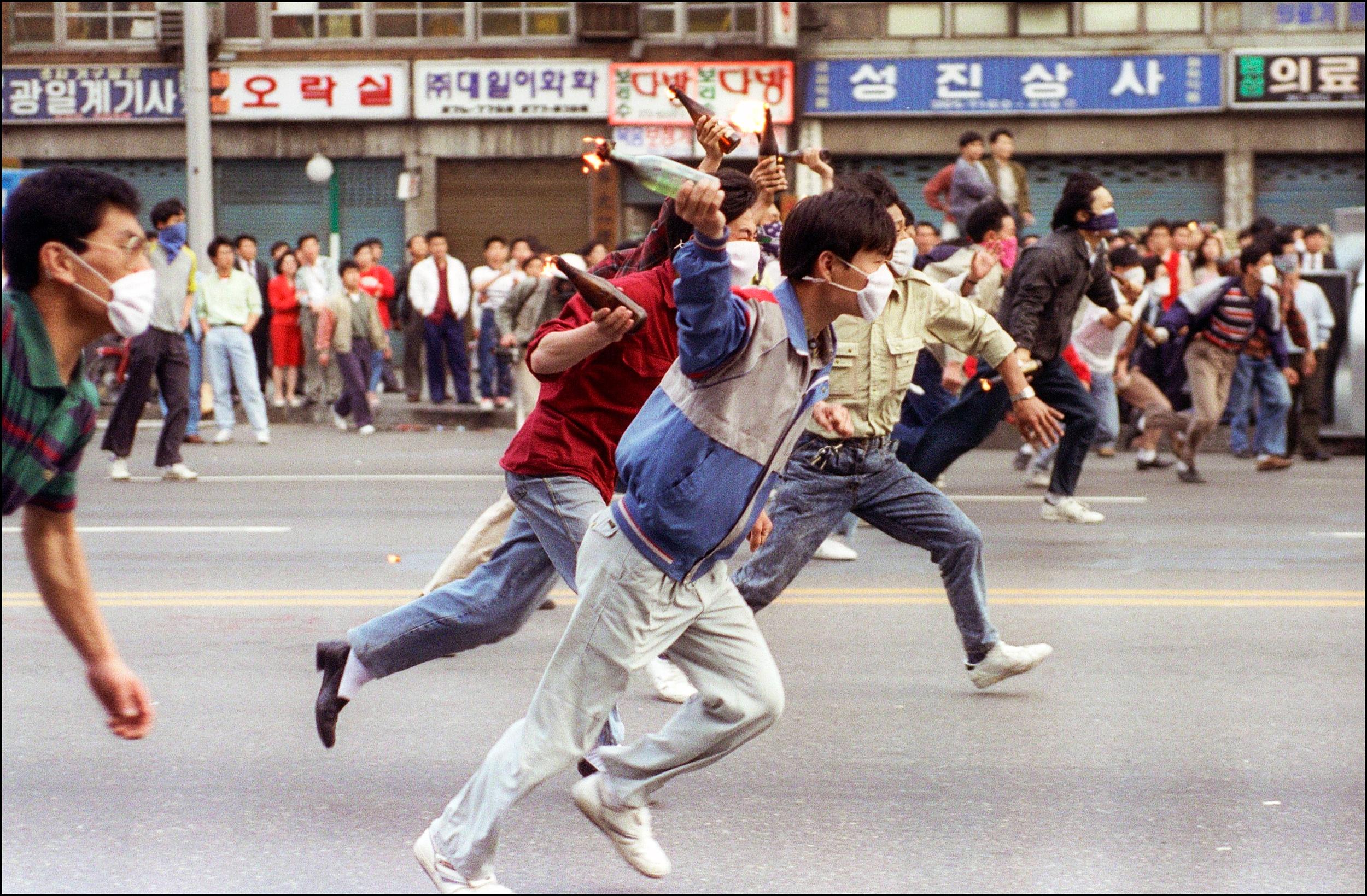

The foundation for injecting socialism—and ultimately communism—into South Korea has been decades in the making, going back to the tumultuous 1980s when student activism for democracy became fertile ground for radical thinking.Those students, now middle-aged, form the backbone of today’s society, although their minds are “stuck in the ‘80s,” according to Min Kyeong-woo, who was a student activist at that time and is now a conservative.

Even when very few people openly support communist ideology, he said, many display communist traits, wittingly or not.

They don’t have a “specific vision” for the future, but just the idea that the current system must be brought down, Mr. Min told The Epoch Times. He sees such thinking as a key factor drawing some of his countrymen closer to communist China.

“What they believe in is a certain ideal society, an ideal society that realizes the perfection of human beings, and they are in power for this purpose,” he said.

“In hindsight, I came to the conclusion that there is no ideal society.

“If there’s no ideal society, then I think communism is only a tool, process, or path to power.”

It was also during the 1980s, as China emerged from a decade of Cultural Revolution culturally and economically destitute, that South Korea began warming to Beijing and other nations in the Soviet bloc.

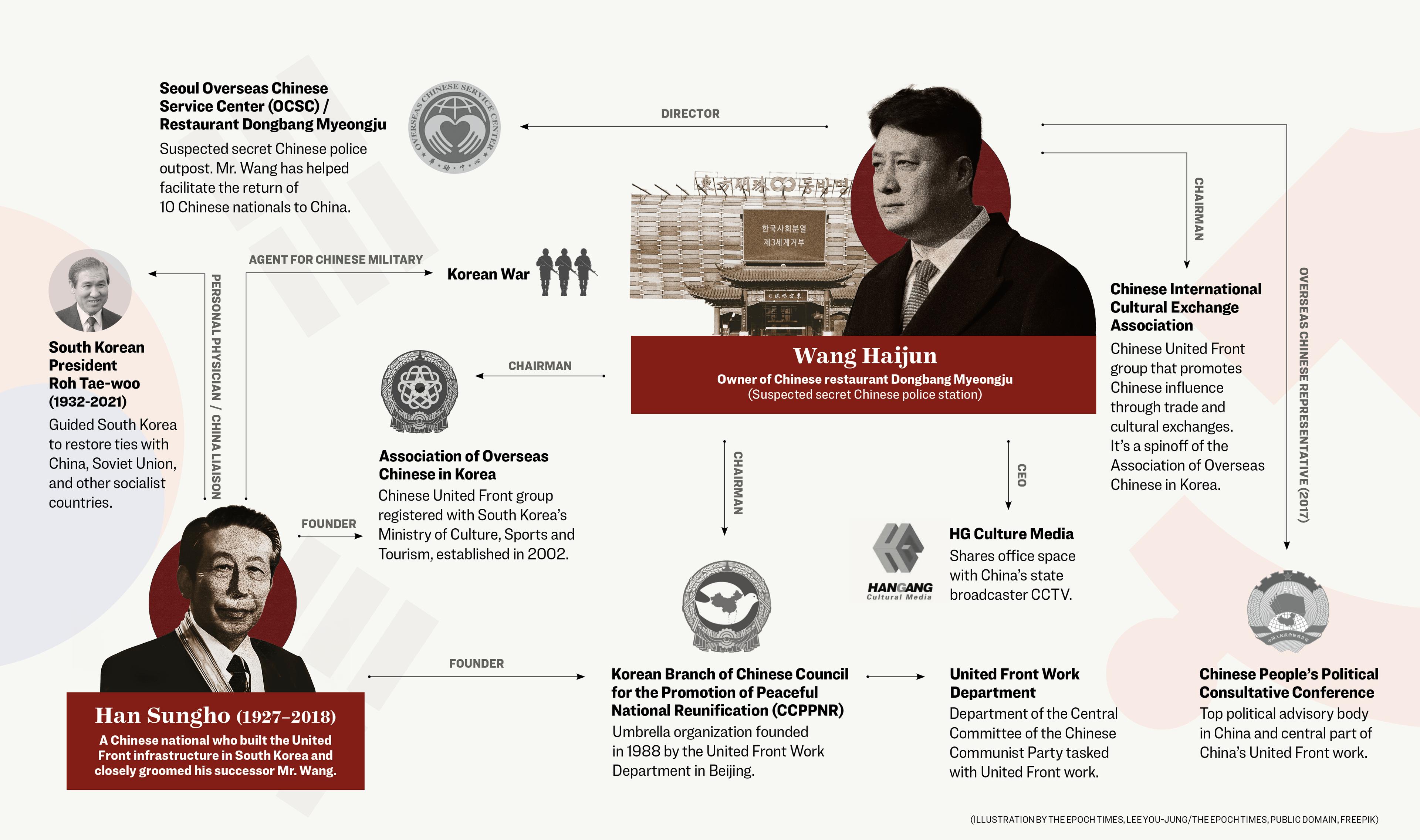

Five days after assuming office in early 1988, Roh Tae-woo, South Korea’s first democratically elected president, summoned his personal physician and campaign aide Han Sungho, a Chinese national who later rose to be a United Front leader in Korea, according to Chinese media reports.

After hugs and jokes, Mr. Roh instructed Mr. Han, who had collected intelligence for the Chinese military during the Korean War, to help “open up a communication channel” in his home area of Shandong Province, China, and pave the way for normalizing diplomatic relations within five years.

About a month later, Mr. Han’s “secret envoy” boarded a flight to China to an “enthusiastic welcome” from Chinese officials, Chinese reports said at the time.

South Korea formally restored ties with China in 1992. The following year, Mr. Han received the Dongbaek Medal, the third-highest Korean national medal of honor, for helping to broker a closer relationship.

Mr. Han was instrumental in building United Front infrastructure and he closely groomed his successor, Mr. Wang, the suspected Chinese agent.

Mr. Wang’s Seoul-based floating restaurant Dongbang Myeongju (Oriental Pearl), which is suspected to double as one of three Chinese police stations in South Korea, is a frequent venue for patriotic events. A second-floor office is adorned with the nameplates of three Chinese front organizations.

“In Korea, no matter what the Chinese do, there is no sense of crisis or security,” Harry said. “The sense of vigilance is completely gone.”

Out of the 10 Chinese front groups that Harry knows, none have official offices, he said.

‘Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing’

Bilateral collaboration deepened rapidly after 1992 as Beijing sharpened all three of the trident’s prongs.

Since 2004, China has become South Korea’s largest trading partner and a top investment destination. Yuan-related transactions were in such demand that South Korea in 2014 set up direct trading mechanisms that bypassed the U.S. dollar.

As economic ties grew, so did the number of Chinese embassy-backed institutions tasked with advancing the regime’s agenda.

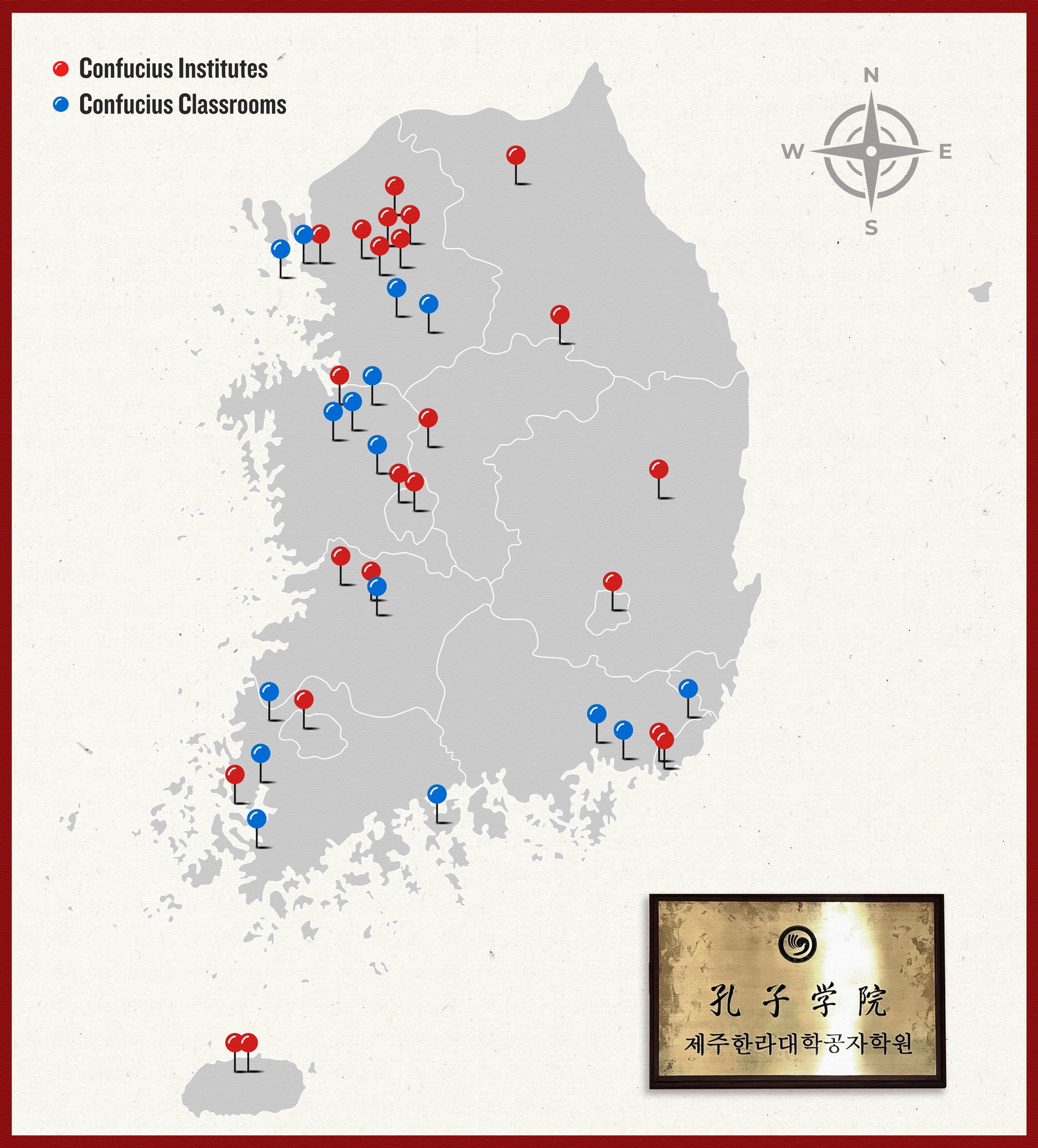

The Confucius Institute, a state-funded Chinese language program that functions as Beijing’s overseas propaganda arm, found its first home in Seoul in 2004 before expanding its global presence—running, at one point, more than 100 such programs in the United States.

Even as national security concerns triggered the closure of more than 90 percent of the institutions in the United States, about 40 Confucius Institutes and classrooms are still active in South Korea; it’s the highest number in Asia.

“They held on, and the criticism died down,” Harry said.

From the top down, the Chinese influence is visible in every front.

Nearly 700 sister and friendship pacts exist between cities in South Korea and China.

By the end of 2023, 600 Chinese civil servants had been sent to work and train in South Korea through a state-sponsored civil servant exchange program.

The Chinese embassy pays for South Korean youths to spend a week in China; it hands them books comprised of Xi speeches to read before they depart and expresses hope that they'll be leaders of future bilateral relations.

At the same time, Chinese propaganda mouthpiece People’s Daily is asserting the CCP’s message with the help of more than a dozen South Korean media outlets that distribute its articles throughout the country.

To draw Chinese tourists, the mayor of Gwangju, who also served as secretary to the president during the Moon administration, is pushing to build a park as homage to a Chinese musician who was best known for composing military anthems for both North Korea’s and China’s ruling regimes. South Korea’s central government, as well as military veterans, have urged him to drop the plan.

“Economy, culture, universities, there is no place that hasn’t been penetrated,” a former counter-espionage official, who requested anonymity, told The Epoch Times.

Through the Arts

It certainly did in the case of the New York-based Shen Yun Performing Arts, whose classical Chinese dance and music performances depicting “China before communism” draw a global audience of more than 1 million each year.

The Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) did so in 2016 after receiving two letters from the Chinese embassy reminding the national public broadcaster of its Chinese broadcasting market. A South Korean court, initially siding with the show organizers, reversed its decision 48 hours before the scheduled performance, despite the thousands of tickets sold.

“That was the mood of the government at that time. The South Korean government itself could not afford to assert its rights or say anything against China,” Kim Ju-hyun, a lawyer for Shen Yun presenters on the KBS case, told The Epoch Times.

“This is not just a matter of canceling a performance contract, but that anyone can be targeted for political purposes.”

Han Minho, who left his post in the South Korean government to lead a campaign to rid South Korea of Confucius Institutes, shared the same view.

Through its maneuvering, he said, the communist regime has “gained confidence that it can control South Korea,” and if South Korea officials “say something wrong, the CCP is bold enough to summon them and scold them.”

For KBS, yielding to Beijing ultimately didn’t prove profitable. Angry at the deployment of a U.S. anti-ballistic missile defense system in August 2016, Beijing blocked Korean music and entertainment from being aired.

Filmmaker Kim Deug-yeong faced his own choice in 2020 when he was trying to sell a sports-related documentary in China. To enter the Chinese market, a Chinese agency told him that he'd have to change his last name to a Chinese name.

“Of course, I said no. I can’t sell my soul to make money,” Mr. Kim, who spent 16 years making “Kim Il Sung’s Children” to tell the story of forgotten North Korean orphans, told The Epoch Times. He said the request was to “deny my nationality and identity as a Korean.”

“I’m a person who makes documentaries and meets audiences with truthful stories, and I have to meet audiences in the future, so I couldn’t choose a lie like this,” he said.

It was an easy choice for a budget film such as his, but when big money is on the line, the Chinese influence would have a harder sway, Mr. Kim said.

A conviction among many who spoke with The Epoch Times is that China’s ruling regime is playing the long game and mobilizing all resources to further its goals, a reason, they said, that Beijing seems so fearful toward Shen Yun’s portrayal of authentic Chinese heritage.

“Who controls the past controls the future,” the film producer said, quoting George Orwell’s dystopian novel “1984.”

“This is the war we are fighting.”