When Luo Zhifei, a Chinese local government employee in rural Guangdong, produced a non-authorized report on bees in 2023, he never expected to get a visit from police, to be questioned about whether he had any foreign contacts, or to be threatened with being sent to a mental hospital.

Luo, who fled to the United States in 2024, recently told the Chinese edition of NTD, sister outlet of The Epoch Times, that he was forced to make up animal farming statistics to match the communist regime’s gross domestic product (GDP) target. He also alleged that his superiors and colleagues fined farmers on bogus charges to fill local government coffers and targeted him for speaking out against such practices.

Luo, 40, was born in a rural area in Jiangxi, a southeastern province near Guangdong. Between July 2020 and summer 2024, the veterinary medicine postgraduate worked in Zengcheng District in Guangzhou for the district Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (BARA), first as an administrator in the agricultural law enforcement section, then as an animal farming statistician in the town of Paitan.

For those born to a common rural family, a job in China’s public institutions, commonly described as an “iron rice bowl,” isn’t easy to get. Applicants are required to take an exam and be interviewed, and they are vetted to make sure they fit a range of criteria; aside from not having a criminal record, they mustn’t show signs of opposition to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) or socialist ideology.

Law Enforcement Abuse

When Luo worked in the agricultural law enforcement section of BARA in Zengcheng District, it was part of his job to produce paperwork for law enforcement cases, and he often received photo evidence from colleagues in the field.“[Many photos] basically showed how they bullied the farmers,” he said. “When I saw the helplessness and anger in the farmers’ eyes, I couldn’t bear it.”

According to Luo, in many cases, officers did not have enough evidence to justify a penalty, but they nevertheless issued burdensome fines and often forced farmers to pay by threatening them.

Zengcheng District is known for the production of lychee, a tropical fruit commonly found in southern China and Southeast Asia.

According to Luo, local lychee farmers are required to use pesticides that specify they can be used on lychee trees.

“As soon as officers found a [noncompliant] empty pesticide bottle near lychees, they would open a case regardless of whether there were other crops around. That evidence is far from sufficient because we couldn’t have known whether the pesticide was used on lychees or other crops,” he said.

“Many farmers said they hadn’t used the pesticides on lychees, and the officers threatened them.”

According to Luo, in 2021, a farmer accused of such misuse of pesticides would be fined 8,000 yuan ($1,110) if he was registered as a sole trader. Those registered as co-ops were fined 10 times that amount. If the farmers contested the fines, the officers threatened to report them to the police and told the farmers that the record would affect their children’s education and job opportunities, Luo said.

In March 2022, Luo voiced his objection in a meeting during which officers were encouraged to hand out more financial penalties in attempts to increase revenue.

“The section chief said that the Zengcheng government was struggling financially, and he encouraged us to increase the number of enforcement cases and the amount of fines,” he said.

“In 2020, Zengcheng had the biggest number of agricultural law enforcement cases among all districts in Guangdong Province. He said we should aim for No. 1 again in 2022.”

According to Luo, in 2021, the district bureau raised 2.6 million yuan (about $361,000) in fines and property confiscations, and the section chief set up an annual target of 4 million yuan (about $555,200) for 2022.

During the meeting, Luo said penalties needed to be backed up by evidence.

“We can’t fine farmers just for the income because of the pandemic, or because the district government can not raise money by selling land,” he recalled telling his colleagues.

Under Chinese law, the state owns all land in urban areas, while rural land is partly owned by the state and partly under local collective ownership. Local governments rely heavily upon income generated from selling the right to use land and on other property-related taxes.

Since 2022, total local government income from selling the right to use land has been in decline for three consecutive years. According to figures published by the Ministry of Finance, in 2022, the figure was 6.7 trillion yuan (about $930 billion), a 23.3 percent drop from 2021. It dropped further by 13.2 percent in 2023 and 16 percent in 2024.

After Luo’s remarks in March 2022, the section chief and a deputy head of Zengcheng District, both of whom were present at the meeting, rejected Luo’s allegation that the fines were unjustified, Luo said.

According to Luo, when he began working for BARA, his superiors demonstrably appreciated the quality of his work, but since the meeting, he felt ostracized by colleagues, and the district head nitpicked his work.

“My world view also started to collapse,” he said. “I began suffering from insomnia and depression. I’ve been seeing the doctor since May 2022.”

Fake Numbers

A year later, Luo was reassigned to work for the animal health supervision unit in Paitan, a town in Zengcheng District, to collect and report statistics on animal farming production.“As soon as I was reassigned, I knew it was a bad job,” he said. “Because I was responsible for reporting the data. If there was anything wrong with the data, I was the one liable. ... However, we were not given any time to collect the data.”

Luo said his boss instructed him and his colleagues to make up statistics.

“He said, ‘We’ve always gone with the national GDP targets.' You know, we have a national target for annual GDP at the beginning of the year,” Luo said. “For instance, the target was around 5 percent in 2023; we would increase all the figures from the previous year by 5.5 percent and fill those numbers in the report.”

Luo said that method was used to produce most, if not all, of the reports.

In 2023, the Chinese regime reported a 5.2 percent annual increase in GDP.

Despite the some 5 percent increases on the books, in reality, most of the farmers in Paitan—including poultry, cattle, and goat farmers—were losing money during and after the pandemic, Luo said.

“Judging by the conversation I had with them, I believe around 70 or 80 percent of the farmers were losing money; only 20 to 30 percent made a profit,” he said.

In December 2023, Luo openly questioned the price of honey in local statistics.

Luo’s unit reported that the price of honey was 50 yuan (about $7) per kilogram, while the price was only about 26 yuan. Luo said he knew the real price because he had conducted an unauthorized survey of beekeepers on his own time and produced a report.

“I knew there was an annual meeting on statistics in December 2023, so I printed my report on bees and the prices of honey, distributed a copy of the report to each attendee, and told them my opinion,” he said.

Luo told his colleagues that if all towns in China used the same data reporting procedure, Beijing would make serious policy errors and that farmers were not able to get the support they needed because they appeared to be making a profit on the books.

“I wasn’t allowed to finish my speech,” he said.

“The consequence this time was more serious. The district-level CCP Commission for Discipline Inspection questioned me on my thoughts and warned me not to leak any confidential information.

“What I never expected was that a policeman suddenly visited me some 10 days later. He asked me about my views on the government and whether I knew any foreigners. I was bewildered.”

Luo said the policeman also warned him against breaking the National Security Law.

Going Public

After another visit from the Zengcheng District’s CCP Commission for Discipline Inspection and Human Resources and Social Security Bureau on May 20, 2024, he livestreamed on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, that evening, to air his grievances and spoke of his opposition to the district BARA’s abuses of statistics and agriculture law enforcement rules. Some two hours later, the livestream was cut off. Luo’s account was blocked, and he began to get more attention from the police.“The local public security station summoned me the next day,” he said. “Before mentioning my livestream, they asked me about the two meetings in March 2022 and December 2023, and asked if what I had said during the meetings was really my view.

“They then questioned the state of my mind ... and asked whether I was in my right mind when I spoke those words.”

Luo said he eventually signed a document under pressure, admitting that he had not been in the right state of mind.

“They threatened me: ‘You are not in a good mental state. If you don’t sign this, if you don’t admit that the contents of the meetings were confidential, I can get a doctor now to establish your mental state. And if the doctor says you are mentally ill, we have the power and the responsibility to immediately send you to a mental hospital.'”

Luo said he was required to submit a monthly report on his thoughts to the police and have a weekly video chat with the police.

He decided to run.

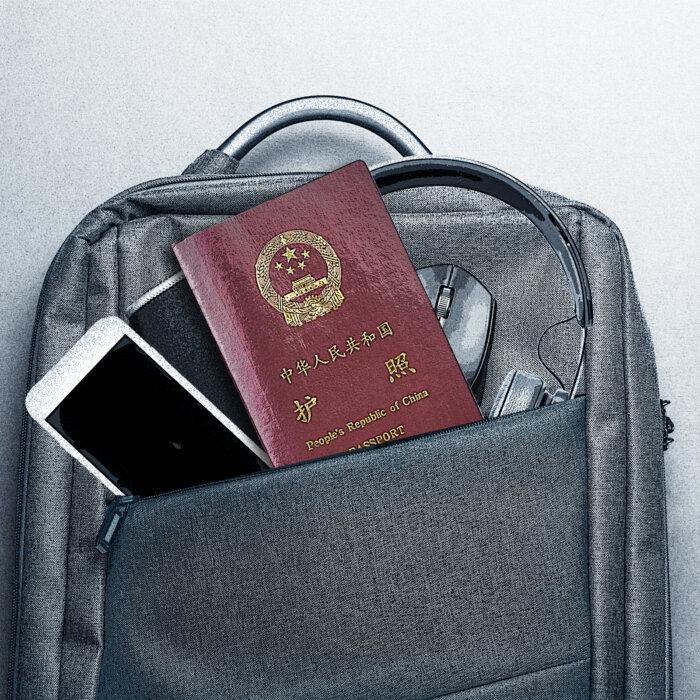

In July 2024, he arrived in the United States and cut all ties with CCP-related organizations.

Speaking of the differences between living in China and the United States, he told NTD: “The most important difference is that people are treated as human beings [in the United States]. People [here] are citizens with the right to vote, can have the freedom of speech, and they live like human beings. In the United States, ... I barely feel the presence of the state.”

Luo said his former employer and the police continued to contact him after he left China and attempted to persuade his mother to convince him to return to the country.

The Zengcheng District BARA didn’t respond to The Epoch Times’ request for comment.