Vikings were some of the most capable navigators of yore, with far-flung expeditions and tales that continue to capture our imagination. Here are some artifacts that may cast some light on their adventures, while at the same time raising questions that seem to steep these people further in mystery.

Sunstone of Lore?

Iceland calcite, possibly the Icelandic medieval sunstone used to locate the sun in the sky when obstructed from view. (ArniEin via Wikimedia Commons)

The sunstone was told of in ancient Viking lore. It was said to allow navigators to find the position of the sun with precision on a cloudy day.

In 2002, a piece of Icelandic calcite was found in a 16th century shipwreck at the bottom of the English Channel. It was resting not too far from other navigational tools. In a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A early last year, a research team led by scientists at the University of Rennes in France said this calcite may be a fabled sunstone.

Icelandic calcite can refract light beams in such a way that the light source is accurately indicated.

Since Icelandic calcite hasn’t been found in burial sites or other shipwrecks, some Nordic studies experts have remained skeptical that this was indeed a sunstone. References to the sunstone are also rare in lore. One such reference is found in the Saga of St. Olaf: Olaf is said to have used a sunstone to find the sun on a snowy day.

Albert Le Floch of the University of Rennes told CBS News that the crystals have probably not been found among Viking artifacts because they degraded. They are vulnerable to sea salt, heat, and other factors.

Kensington Stone: Evidence of Early Viking Expedition in America?

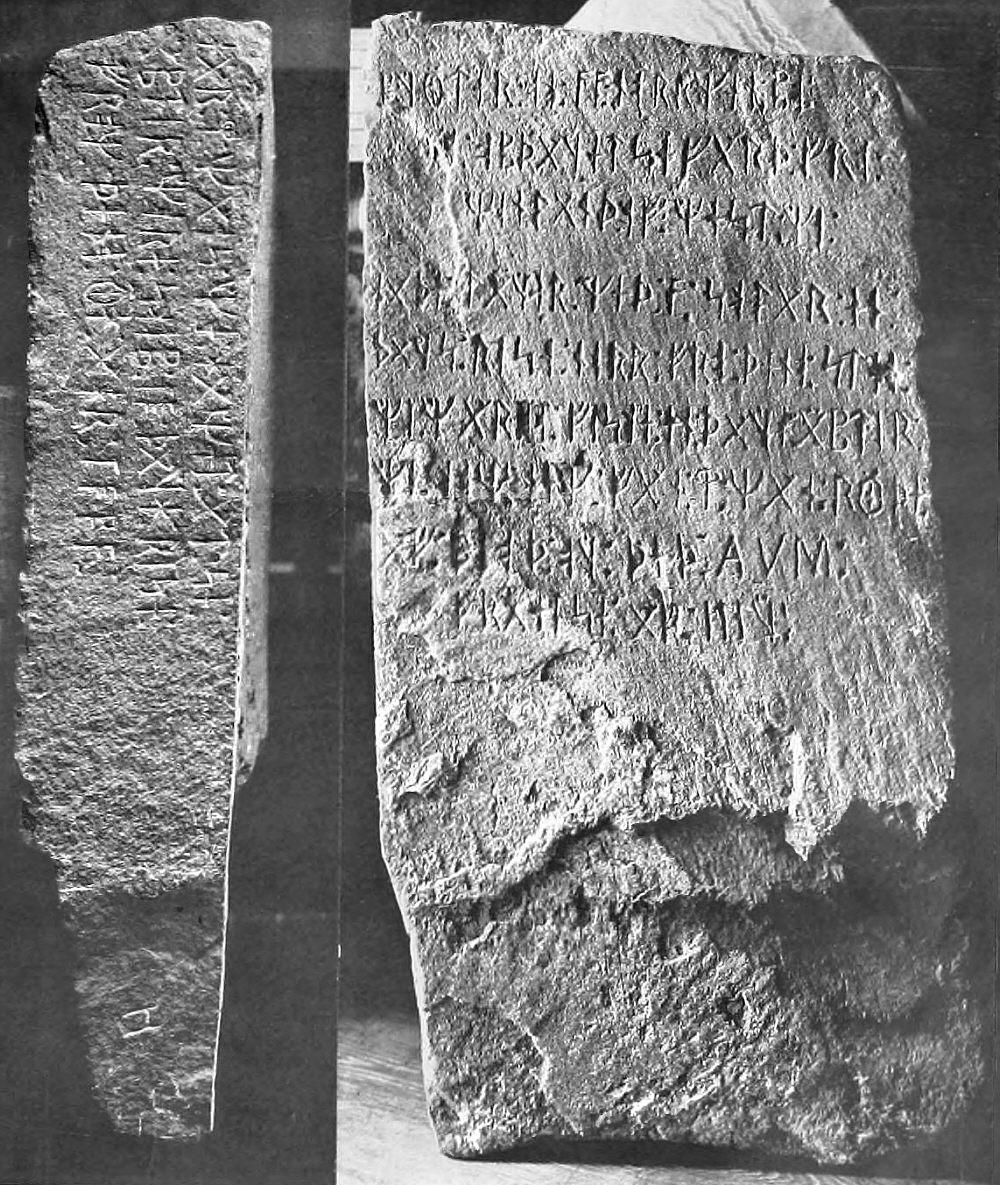

Images of the two carved faces of the Kensington Rune-Stone, from George Flom’s book “The Kensington Rune-Stone: An Address,” taken in 1910. (Illinois State Historical Society via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1898, Swedish-American farmer Olof Ohman said he discovered on his Minnesota property a slab of stone inscribed with Viking runes. The inscription told of an expedition in the year 1362 that ended in the loss of 10 men at the hands of Native Americans.

A translation of the runes reads: “Eight Geats [South Swedes] and 22 Norwegians on acquisition venture from Vinland far to the west. We had traps by two shelters, one day’s travel to the north from this stone. We were fishing one day. After we came home, found 10 men red with blood and dead AVM (Ave Maria). Deliver from evils!”

Though the Vikings are known to have reached what is now northern Canada as early as 1000 A.D., this rune-stone would be evidence of European expeditions further south preceding Christopher Columbus’s arrival in the New World.

In a 2004 article, the Seattle Star Tribune explains why the authenticity of this stone has been called into question. Documents written in 1885 by a Swedish tailor named Edward Larsson revealed the secret use among tradesmen of a form of runes. Some runes used in Larsson’s documents correspond to those on the stone, according to Swedish linguists cited by the Tribune. They say these runes did not exist in the 14th century, but are particular to this more modern code.

Michael Michlovic, professor of anthropology and chairman of the department of anthropology at Minnesota State University–Moorhead, told the Tribune: “My opinion is this once again nails down the case against the Kensington Runestone … This new evidence is really devastating.”

Geologist Scott Wolter, on the other hand, remains convinced that the stone is genuine. He said the weathering of the inscription tells him it is much older, that it could not have been produced in the late 19th century.

Ulfbert: The Sword So Advanced It’s Like Magic

An Ulfberht sword displayed at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg, Germany. (Martin Kraft via Wikimedia Commons)

The Viking sword Ulfberht was made of metal so pure it baffled archaeologists. It was thought the technology to forge such metal was not invented for another 800 or more years, during the Industrial Revolution.

About 170 Ulfberhts have been found, dating from 800 to 1,000 A.D. A NOVA, National Geographic documentary titled “Secrets of the Viking Sword” first aired in 2012 took a look at the enigmatic sword’s metallurgic composition.

Modern blacksmith Richard Furrer of Wisconsin spoke to NOVA about the difficulties of making such a sword. Furrer is described in the documentary as one of the few people on the planet who has the skills needed to try to reproduce the Ulfberht.

He commented on how the Ulfberht maker would have been regarded as possessing magical powers. “To be able to make a weapon from dirt is a pretty powerful thing,” he said. But, to make a weapon that could bend without breaking, stay so sharp, and weigh so little would be regarded as supernatural.

Furrer spent days of continuous, painstaking work forging a similar sword. He used medieval technology, though he used it in a way never before suspected.

SEE MORE on the Ulfberht: “Mysterious Viking Sword Made With Technology From the Future?”

Follow @TaraMacIsaac on Twitter and visit the Epoch Times Beyond Science page on Facebook to continue exploring the new frontiers of science!