The leaves, though little time they have to live, Were never so unfallen as today, And seem to yield us through a rustled sieve The very light from which time fell away.

A showered fire we thought forever lost Redeems the air. Where friends in passing meet, They parley in the tongues of Pentecost. Gold ranks of temples flank the dazzled street.

It is a light of maples, and will go; But not before it washes eye and brain With such a tincture, such a sanguine glow As cannot fail to leave a lasting stain.

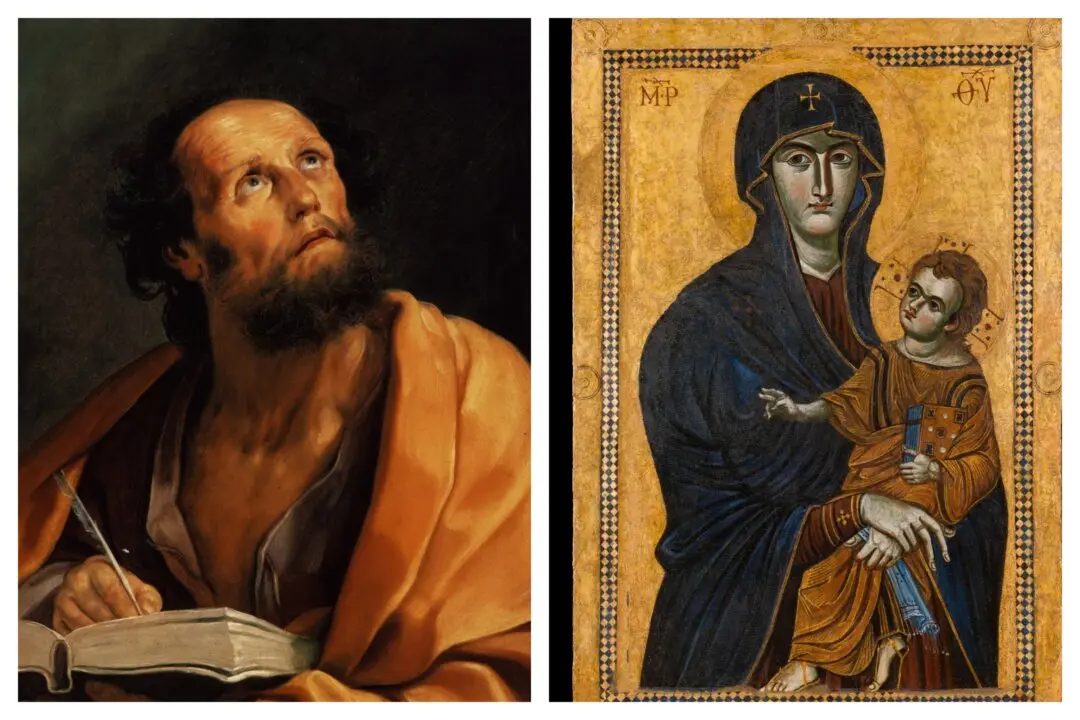

So Mary’s laundered mantle (in the tale Which, like all pretty tales, may still be true), Spread on the rosemary-bush, so drenched the pale Slight blooms in its irradiated hue,

They could not choose but to return in blue.

I’ve never seen Portland, Connecticut, in the autumn. Whenever I find myself at home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, at this time, I pine for the customary autumn hues that Portland must have. Fortunately, a poem by Richard Wilbur (1921–2017) is ready to supply me with a colorful autumn tableau in “October Maples, Portland.”Despite the fact that he was poet laureate from 1987 to 1988, I doubt whether most people recognize his name. He died only a few years ago in 2017 after a lengthy career in writing that started with the publication of his first poem at the age of 8.