Chaucer famously describes the month of April in the prologue of “The Canterbury Tales“ as the time in which people start longing to go on pilgrimages. (“Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages.”) April is also the month of Paul Revere’s famous ride to warn the colonists of the approaching British soldiers, as described in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

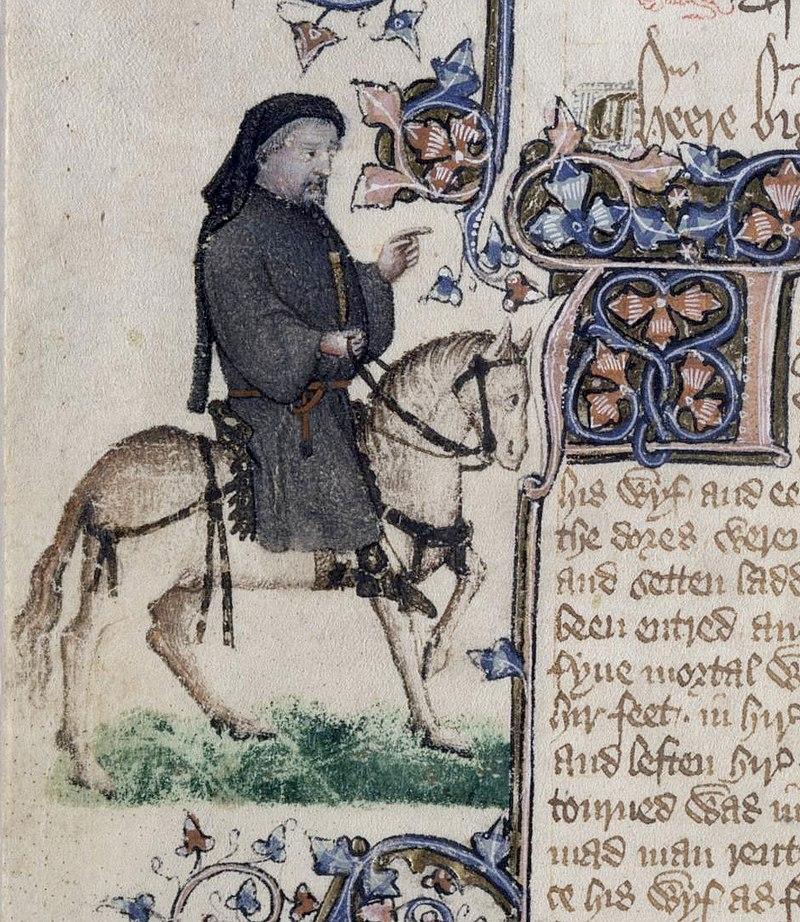

Geoffrey Chaucer from the Ellesmere Manuscript. Public Domain