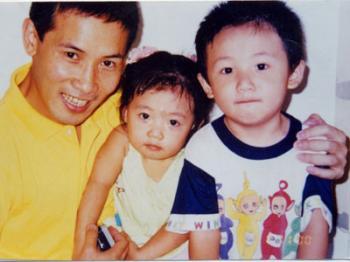

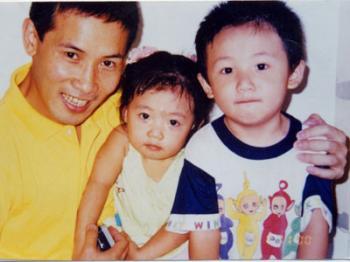

A photograph of Zhang, a letter to his wife, and a letter to the U.S. Congress, which were smuggled out of the prison by inmates in 2004, are among the few records of his life obtained over the last decade. Unable to contact the outside world or his wife and two children, his current condition is unknown. He is known to have been tortured by the Chinese authorities in the early years of his arrest.

Calls to Shi Hui Prison in Guangdong Province, where Zhang is being held, were not returned as of press deadline.

Huang practices Falun Gong, a Chinese meditation practice based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance. The practice was banned by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1999, shortly after a state-run survey estimated that there were at least 70 million people practicing Falun Gong in China.

“The website would present uncensored news for people, especially for the Chinese, because the Chinese have no access to free news,” Huang said by telephone from Illinois this week.

By September 2000, he joined the media’s Beijing team and worked on the international news section. Later, he moved to Zhu Hai City in Guangdong Province, in Southern China, where he met Zhang, the editor-in-chief of the China edition.

In December 2000, while they were working on the news website, a gentle knock came at the door.

“When I opened the door, there were over 10 policemen standing there,” Huang recalled.

Press Freedom

The despotic state of the press in China is no secret. On a scale of press freedom, China was ranked 168 out of 175 by Reporters Without Borders in 2009—placing it just seven spots away from being the worst country in the world in this respect.The International Federation of Journalists also maintains a list of cases of abuse against media in China. Its June 2010 bulletin includes assaults against journalists in Guangzhou Province and a list of media bans issued by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department.

Torture and Imprisonment

After the 10 staff members of The Epoch Times in Zhu Hai City were arrested in December 2000, they faced close to half a year of repeated interrogations.“They would change the policemen several times,” Huang said. “They asked me some details about our work on the website. Sometimes they would curse me. Some days they would curse me for eight straight hours. It was horrible.”

Zhang had it even worse. Months later, when sentences were handed out, Huang was sentenced to five years in prison and Zhang to 10 years.

The two were sent to Si Hui Prison in Guangdong Province in 2000, yet they wouldn’t be heard from again until 2003. The guards kept a close watch and also used other prisoners to monitor them to prevent them from communicating with one another.

Zhang wasn’t able to talk for a long time. When he was finally able to communicate with Huang, he indicated that he had been tortured by the CCP authorities. It was the last time Huang would see his friend.

Among the torture methods used on them was one resembling a crucifixion. The subject is forced to lie on a wooden plank. Their arms are then tied stretched out on either side, and their heels are tied down on either side of the wooden plank. Chinese refer to the torture method as “The Plane,” but it is also called the “Death Bed.” Victims are often kept stretched out this way for days.

Zhang was in his 30s when he was taken away by the CCP. While he was barred from taking care of his family over the last decade, his wife and two young children struggled to get by in the United States.

The situation in prison was difficult. Huang noted that he and the other prisoners performed slave labor for 16 to 18 hours each day, making everything from plastic flowers to strings of Christmas lights. At one point, when a shipment of pistachios arrived from the United States, the inmates were forced to open the pistachio shells using large pliers.

“The pliers left big blisters on my hands, very painful,” Huang recalled.

Since he practiced Falun Gong, brainwashing seminars were also a regular part of Huang’s sentence. He was forced to watch propaganda videos slandering Falun Gong and read state-issued materials promoting hate against the group.

“They tried to make me give up my beliefs,” he said.

Huang was released at the end of 2005 and was awarded a scholarship to Ohio State University in 2008. After earning his master’s degree in mechanical engineering, he found a job in Illinois.

He shared his hope that Zhang would be released on the scheduled date this month, but noted that “even his wife doesn’t know much about his current situation.”

“We know that Zhang’s health is not good,” he added.

Their arrests represented “a very big loss for the freedom of Chinese media,” he said.