The independent budget watchdog has poured cold water on pre-election tax cuts, saying the chancellor only has a “tiny” headroom compared to risks.

Richard Hughes, chair of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), told peers on the Economic Affairs Committee that the projected £13 billion headroom is well within the margin for forecasting error.

He also said current policies on borrowing are not sustainable in the long run, with the next five to ten years being a “window of opportunity” to address demographic and other issues.

With inflation falling faster than expected since the last OBR forecast, lowering the cost of paying debt interests, the government is forecast to have a headroom of £13 billion against its self-imposed target of getting debt falling as a share of GDP in five years.

However, the figure is “a fraction of GDP” while “forecasting error for borrowing is anywhere between 2 and 4 percent of GDP,” Mr. Hughes told the committee.

“That is a tiny number compared to the risks that you face.”

The watchdog also said the OBR has to make its own assumptions for long-term forecasts as he blasted the government for its lack of future spending plan.

The OBR was given “a lot of detail” on departmental spending plans up until March 2025, but “virtually nothing” beyond that, he said.

Mañana Rule

The watchdog described the five-year rolling target as a “Mañana rule,” meaning it’s always in the future.“The point of which you have to get debt falling, as always, is always five years ahead, it never seems to be realised. So it doesn’t necessarily get debt falling at outturn,” he said, adding that it incentivises chancellors to take advantage of the extra time.

“And you saw that in our last forecast ... the chancellor got a windfall of around 20-odd billion pounds, and he spent all of it because he had an extra year to get debt falling.”

However, Mr. Hughes said there’s “no perfect rule,” and there is no way to meet a fixed target when “a pandemic comes along, and energy crisis comes along.”

The UK’s public sector net debt was at a record £2.69 trillion as of Dec. 2023, or around 97.7 percent of GDP, remaining at levels last seen in the 1960s.

Mr. Hughes said he’s not expecting any problems with the debt market in the near term, but the current fiscal model will not be sustainable in the long term with an ageing society.

“Demographic changes, as well as other structural changes in the UK economy, are likely to drive up spending, not least on health, but also on other areas, if you assume we keep roughly the same tax system, and so the tax stays roughly constant as a share of GDP,” he said.

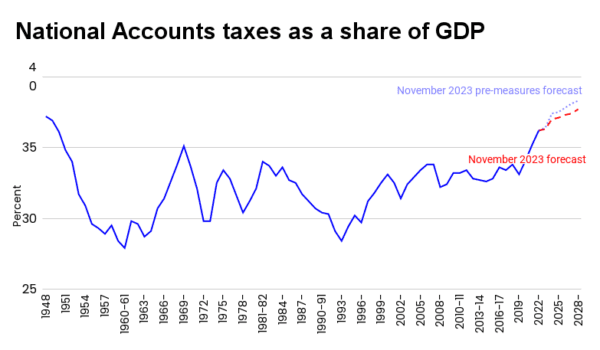

The UK’s tax burden—tax receipts as a share of GDP—in the financial year 2022/2023 was 36.2 percent, the highest since 1950. It’s projected to reach 37.7 percent in the year 2027/2028.

Tom Josephs, member of the budget responsibility committee at the OBR, told peers that the UK is “somewhere in the middle of the pack” among advanced economies.

Immigration, AI Unlikely to Help

According to Mr. Hughes, immigration is unlikely to make a difference to public finance, particularly as the profile of the UK’s new immigrants changed with its post-Brexit immigration system.Immigrants from the European Union were “more likely to be of working age, ... tended to bring fewer dependents, and ... tended to be more likely to return home at some point in their lives,” thereby reducing the burden on the UK’s education, health care and pension systems, he said, adding that the UK’s new migrates appear “broadly like the rest of the UK population.”

“So there’s not a particular economic or fiscal premium attached to migrants compared to UK citizens,” he said.

Asked what would happen to net debt if net migration is brought “right down to 100,000 in the next five to six years,” he said it would “make a marginal change.”

Asked whether AI would transform productivity as people are hoping, Mr. Hughes said, “I think it offers hope to improve the productivity of the health service, but we don’t forecast on the basis of hope.”

He also cautioned against hoping innovation can be “the magic bullet” because the United States, which is “at the frontier of innovation and health care,” spends “a much bigger fraction of its income on health care than we do.”

Window of Opportunity

However, Mr. Hughes believes there’s a “window of opportunity over the next five to ten years to take action” because demographic changes have different impacts in the short term and the long term.“In particular, the fact that birth rate has been falling, that reduces the cost of education in the near term, but that’s not good news for demographics in the long term, because that means you’ve got fewer work, fewer workers, fewer taxpayers, supporting growing numbers of people who are retired. So there is a window of opportunity over the next five to ten years to take action in these kinds of areas to deal with demographic challenges,” he said.