Experts predict that by 2040, people will control smart devices with their thoughts due to advancements in ’smartbrain' technology.

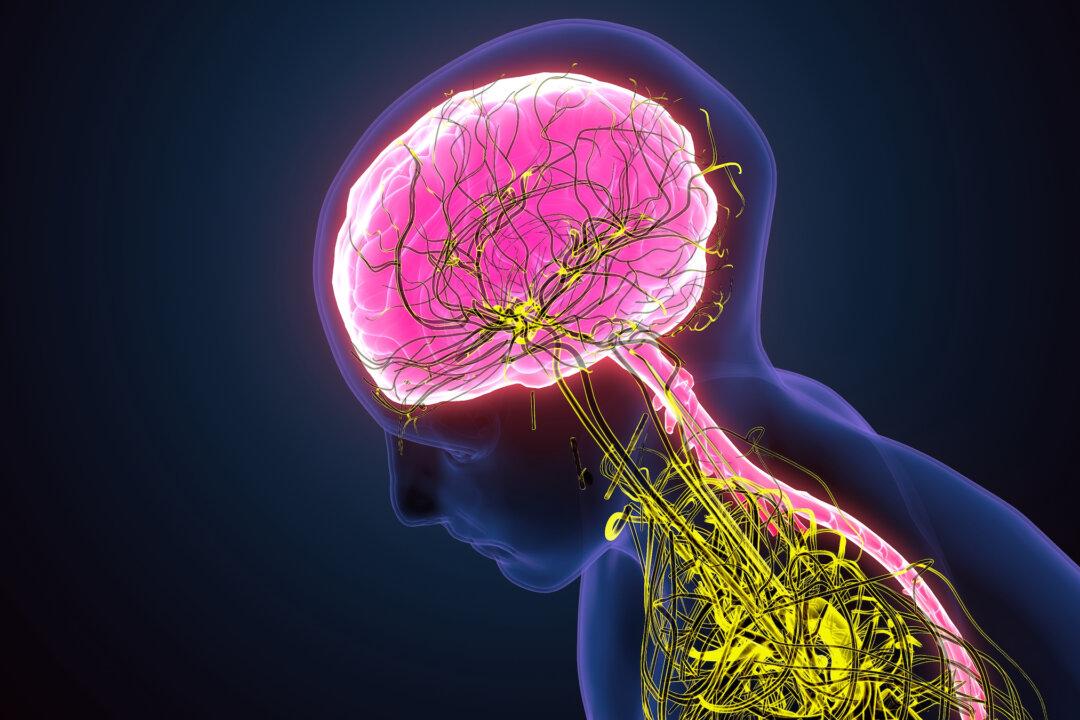

A smartbrain, or Brain-Machine Interface (BMI), is a wearable or implanted device that directly links the human brain to smart devices like phones, computers, and robotic limbs.