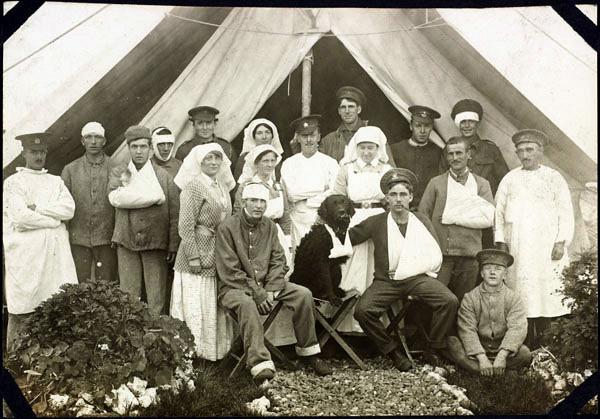

The story of Canada’s nursing sisters is one of courage, loyalty, compassion, and devotion to duty as they endured the unimaginable hardships of war to care for the casualties of the battlefield.

Working in substandard and often dangerous conditions that they were ill prepared for, especially in the First World War, they bravely adapted to the situation and drew on their knowledge to treat and comfort the soldiers in their care.