The world has somewhat gotten used to the gradual meltdown of China’s foreign exchange reserves, down another $29 billion in February to an even $3.2 trillion, much lower than the $4 trillion peak in 2014.

What the market hasn’t figured out is how long this drain will continue and who is actually responsible for the capital outflows behind the foreign exchange drain.

Some commentators like Peking University professor Michael Pettis say China has more than plenty liquid reserves available to defend the currency, given its large trade surplus.

But he also warns, however, that losing $150 billion of reserves per month for a little bit longer will soon trigger a crisis of confidence.

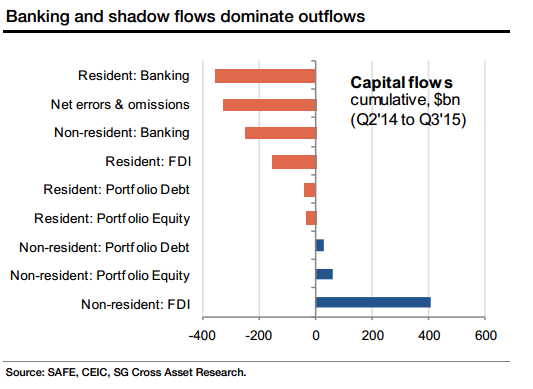

A new report by investment bank Societe Generale sheds light on the origins of the outflows and concludes that a devaluation of the Chinese currency to at least 7.5 yuan per dollar is very likely in 2016.