NEW YORK—With plans for 80,000 new affordable housing units on the table, every neighborhood will have to take its fair share, experts say. This means nearly every community is aware they will have to accept more density, putting some on the immediate defensive.

The administration has stressed that the impending wave of development will be accompanied by sufficient community input; that development will have to suit the communities’ needs. But those familiar with the 150-day review process know time flies by all too quickly, sometimes before community members understand what is going on.

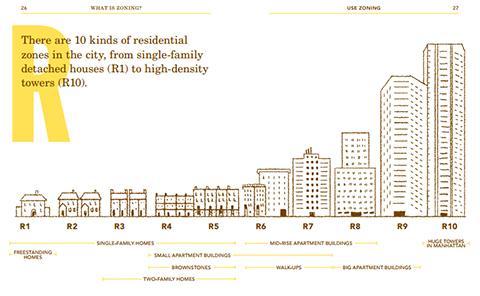

What is ULURP? How much affordable housing should a project bring if an M-1 site is being rezoned to R-8? Waiting for developers or the Planning Department to come in with plans for rezoning isn’t a fair enough approach, some Council members say.

Throughout the summer, Council members of the western half of Brooklyn have been delivering a message at the street level, giving residents the tools to hold them accountable for responsible development.