Books are important, especially in an authoritarian society where the state decides what goes to press. This gives some context to the piece run by China’s state-run People’s Daily on Oct. 15, listing the dozens of works that national leader and Communist Party head Xi Jinping counts among his favorites.

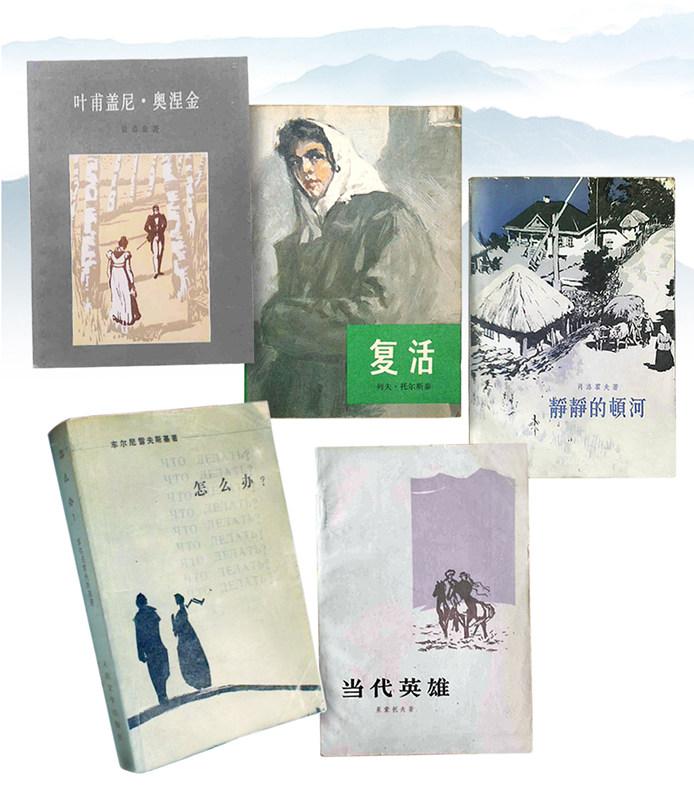

The selections — titles included range from ancient Chinese masterpieces to the novels of Russian and French giants, with a smattering of other works from East and West alike — present Xi as a worldly statesman grounded in classical thought. At the same time, they reflect the ordeals he suffered growing up as the son of a disgraced cadre in a time of frenzied political chaos.

In the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, a teenage Xi was denounced, lost his half-sister (she is thought to have hanged herself due to political torment) was moved to the countryside as part of the “to the mountains and villages” program in which tens of millions of urban “sent-down” youth sacrificed their best years in rural labor instead of education.

According to the People’s Daily, which took its list and narrative from a Communist Party commission, Xi did most of his reading in his adolescence. He gained an appreciation for the breadth of Tolstoy, saying that he liked “War and Peace” the best, while describing “Resurrection” as a book “full of spiritual reflection.”