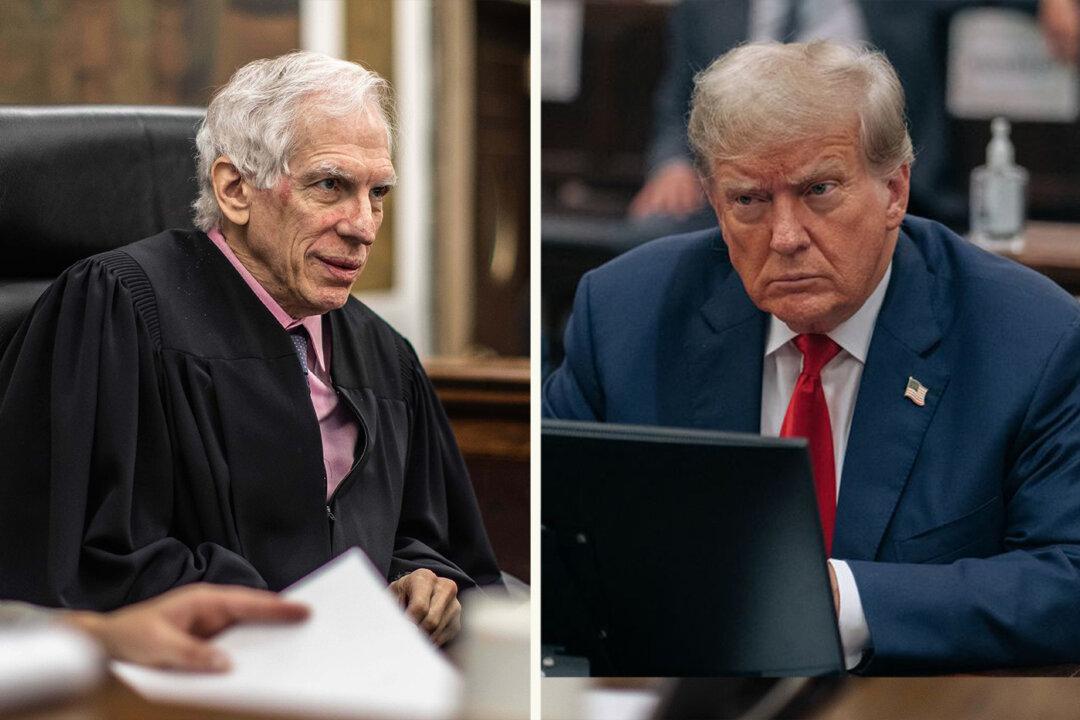

New York Supreme Court Justice Arthur Engoron, presiding over the civil fraud trial against President Donald Trump, responded in court filings on Dec. 6 to the former president’s accusation that he acted unlawfully.

President Trump and his attorneys made no protest when Justice Engoron first issued his gag order, he wrote, and besides that communications between a judge and his clerks are “sacrosanct.”