The Supreme Court limited the reach of the federal Identity Theft Penalty Enhancement Act, unanimously rebuffing the Biden administration’s efforts to prosecute a man already convicted of Medicaid fraud with a separate charge of aggravated identity theft arising out of the same fraud case.

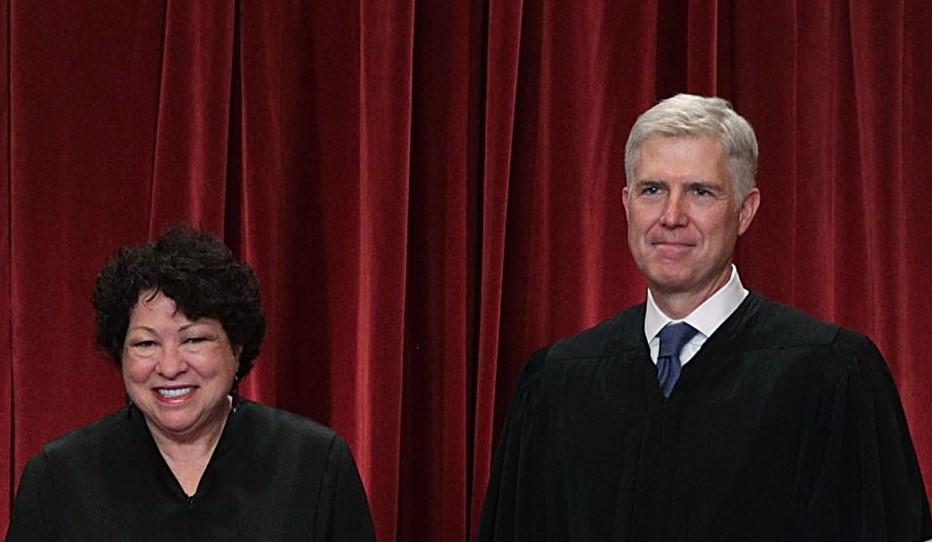

The 9–0 opinion (pdf) in Dubin v. United States (court file 22-10) was issued on June 8 and authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor. Justice Neil Gorsuch filed a concurring opinion.