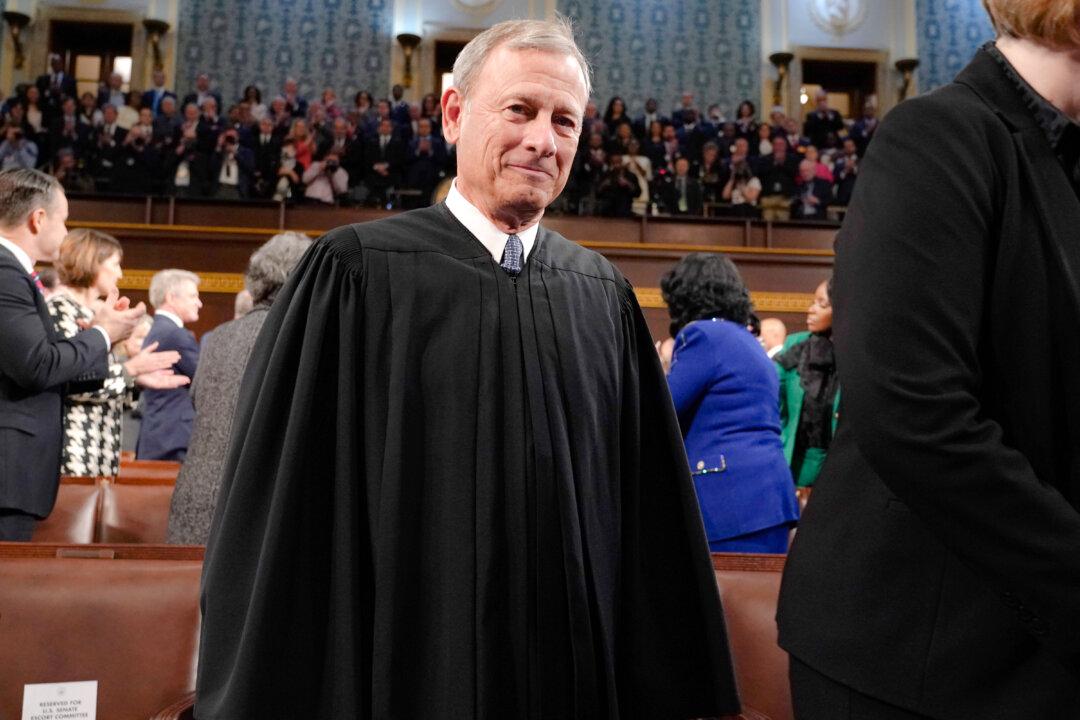

Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts on May 7 emphasized the importance of maintaining the judiciary’s independence as a check on government power during a visit to his birthplace of Buffalo, New York.

Roberts, who presides over Supreme Court arguments and oversees the federal judiciary, was participating in an on-stage conversation with U.S. District Judge Lawrence Vilardo amid the 125th anniversary of the federal district court in western New York.