Just as Western opinion seemed to be settling resignedly into a leftward phase in political direction, with the most officially leftist government in German history likely to emerge in a three-party pantomime-horse regime, the Bidenization of America to continue at least to the midterm elections, and no sign of a drift even to the center-right in Canada or France, the picture has changed quite dramatically.

The evisceration of the Democrats in the elections from West Virginia to Seattle last week and especially the direct repudiation of the Biden, Obama, and Clinton Democrats in Virginia, and a hair-raising escape by the governor of New Jersey (Philip Murphy), which was assumed to be a walk-away, will produce an agonizing and fretful reappraisal among the Democrats, unless they leave the steering gear in the hands of the doctrinaire left who now comprise almost 45 percent of the Democratic delegation in the House of Representatives.

These people consider House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) to be to the right of them and the other House Democrats consider her to be the left of them, and after many years of fancy footwork, Pelosi’s position appears to be precarious.

To the disconcertion of the traditional Republican Bush–Romney–McCain interests, the power of Donald Trump within that party appears unshakeable. The shambles of the American economy, the open artery at the southern border, the absurd and avoidable fracas over compulsory COVID vaccination, soaring urban crime rates, and the debacle in Afghanistan make Trump seem prophetic to millions who had not previously supported him. The Durham special counsel investigation into the origins of the Trump-Russian hoax can’t fail to generate some support for the former president.

France

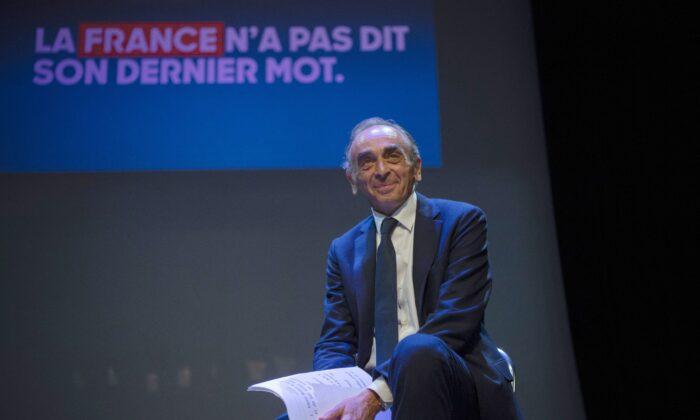

But perhaps the most striking evidence of the sudden revival of a responsible and even creative right is in France, where the extraordinary rise of Eric Zemmour has, as France frequently does, astounded observers. Just five years after the rise of Emmanuel Macron from complete obscurity, on a platform of complete Euro-integration, personing the barricades against climate change, and pro-private enterprise initiatives in taxes and regulations, Zemmour, a party-less television and newspaper commentator who hasn’t announced his political candidacy but is campaigning for the presidency, is now threatening to unite the right—the old Gaullist and anti-Gaullist Republicans—and to give Macron a rousing challenge next year.Zemmour is running almost as a traditional Gaullist, hinting at a much more autonomous notion of participation both in Europe and in NATO and demonstrating once again that there were always significant reservations in France’s commitment to the “ever-closer Europe” that all the EU countries were supposedly pursuing.

French particularism, as de Gaulle personified, isn’t immutable but is imperishable. The old National Front of Jean Marie Le Pen and his daughter Marine Le Pen seems virtually to have collapsed, and this French phenomenon, unique among prominent countries, of a completely new political personality arising and forming a new political party and making a huge impact on traditional election patterns, seems ready to repeat itself. This is essentially what occurred when General de Gaulle entered elective politics in the late ’40s and then withdrew for a decade and said he would await the call of the people. This more or less came in 1958, with a little prompting from the general himself.

Macron also mysteriously emerged from the partisan mists five years ago after the completely unsuccessful socialist presidency of François Hollande. Macron was 39, had never sought elective office, but stated his position, announced the formation of a new party, and swept the elections. The French political parties don’t have the habit of longevity and even the Communists have changed their name.

Zemmour is a slightly sinister-appearing and bookish man who speaks with great and learned articulation even by French standards and is a famous television personality, a widely viewed news analyst and commentator, and an acerbic and discerning writer capable of stirring profound reservations about public policy in France.

He frequently raises the question of the Islamic penetration of France in controversial ways and has been convicted once, though that is under appeal, and acquitted six times on charges of inciting racial antagonism. His book, “The French Suicide,” has sold more than a half-million copies in five years. Polls indicate that he would run second to Macron and in the absence of majority under French rules, there would be a runoff election between the two top contenders and a united right should win.

Zemmour’s approach to deep visceral anxieties in the French public in a culturally impeccable, perceptive, and artistically formulated way makes it difficult for his opponents to label him as simply a rabble-rousing racist, as they did with Jean Marie Le Pen and to some extent his daughter. (Marine Le Pen finally expelled her father from the party he founded, when he was 87 years old, because of his incorrigible tendency to truckle to Holocaust-deniers. Zemmour, a Jew, is irreproachable on such issues.)

While Zemmour hasn’t announced his candidacy for the presidency, in France, these candidacies can be got up very quickly. Macron has already tacked to the right in some areas, after bungling the “yellow jacket” tax revolt violence last year. He has required that everyone be recognizable in public, aiming chiefly at Muslim women, and has enforced the oversight of mosques and other houses of worship to ensure against and suppress the incitement of mass hostility or violence.

Germany

The German election has created an astonishing variety of possibilities. The left-wing Link, essentially the continuation of the communist regime of East Germany, is deemed by all other parties to be unfit for a coalition. But the other five parties that have crossed the threshold of 5 percent of the vote and are qualified for representation could all be eligible.There seems to be little enthusiasm for the continuation of a grand coalition between the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats, the only parties that have led a government in the history of the Federal Republic. Both parties have suffered such attrition at the hands of third parties, and are down to the mid-20s in percent of electoral support.

The Greens (14.8 percent) have been in government before and behaved fairly responsibly, and the Free Democrats (11.5 percent), a solidly bourgeois small business party, has often served effectively in government, (Walther Scheele, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, Otto von Lamsdorf). The German Alternative (11.3 percent), is generally conservative but has been deemed not respectable because of occasional flamboyant positions on illegal immigration.

The fact that the various party leaders are still interviewing each other seven weeks after the election indicates the complexity of the process. But the main slippage is from the center-right to the right, not to the left; Germany’s political status is fluid, though not volatile.

Latterly, Germany has flirted with the international left, and has become somewhat ungrateful toward the Americans to whom it owes its integration as a postwar ally and ultimately also its reunification. Germany has historically been prone to imagine that it’s skillful at dealing with the Russians, but apart from the short-lived and completely cynical Nazi-Soviet Pact, there is no evidence of that since Bismarck’s League of the Three Emperors 140 years ago.

If the Christian Democrats, the Free Democrats, and the German Alternative Party were ultimately to form a coalition, Germany would take the lead in the procession toward the right of center, which may have been confirmed in the American elections last week. The Americans, British, Germans, and French seem all to be moving, quite unexpectedly, back from the left-center, and for the same reason: Governing from the left doesn’t work in any advanced country.