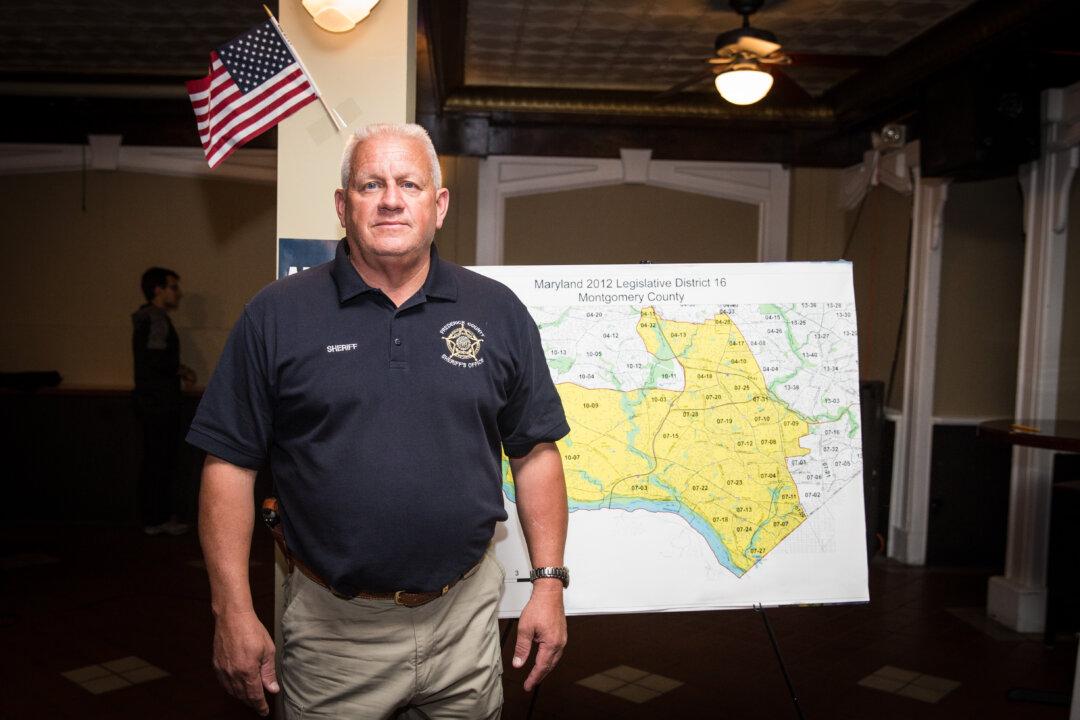

BETHESDA, Md.—Sheriff Chuck Jenkins swears by the 287(g) program, calling it a “force multiplier” for immigration enforcement and an effective way to keep criminals off the streets.

The 287(g) program was added to the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1996 under President Bill Clinton, and is a cooperation agreement between Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and a state or local law enforcement agency.