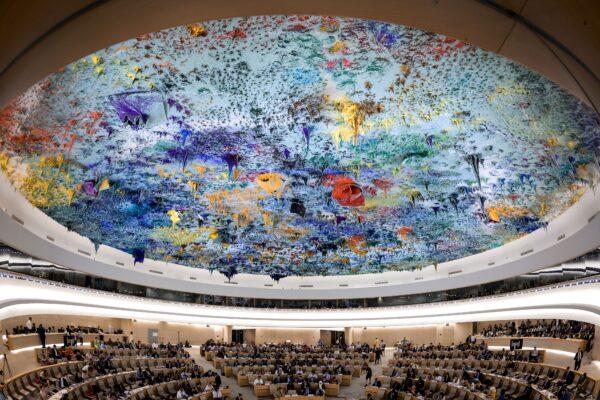

A United Nations whistleblower has accused the organization’s human rights agency of endangering Chinese rights activists by disclosing their names to the Chinese regime.

The list of names provided to the Chinese authorities included Tibetan and Uyghur activists, some of whom are U.S. citizens or residents, according to Fox News.

Reilly said that the practice has continued since 2013.

The United Nations and the OHCHR did not respond to inquiries from The Epoch Times.

In a Dec. 14 briefing, UN Human Rights Council spokesperson Rolando Gomez dismissed the allegations as a “distortion,” saying that “under no circumstances the Office of the High Commissioner divulged names of human rights defenders coming to the council,” Fox News reported.

Reilly, an Irish and British dual national, also accused the organization of retaliating against her in response to the complaints.

“Instead of taking action to stop names being handed over, the UN has focused its energy on retaliating against me for daring to report it. I have been ostracized, publicly defamed, deprived of functions, and my career has been left in tatters,” Reilly said.

She also said the UN approved of Beijing’s request for the name list even though it denied a similar request from Turkey.

Reilly had also reported such practices to senior staff members and through other internal channels, but saw no immediate action from the organization until the Irish government intervened in 2016, the Government Accountability Project said.

The advocacy group further noted the disappearance of Chinese lawyer and activist Cao Shunli at a Beijing airport in September 2013, while Cao was on her way for a UN Human Rights Council session in Geneva. The arrest took place six months after Reilly’s first internal report. Cao died in detention in China six months later after being denied medical treatment.

Reilly said she had suffered from a range of alleged reprisals due to her speaking up, including being discriminated for promotion, excluded from meetings, and receiving prejudicial performance evaluations.

Responding to Gomez’s comments, Reilly said that the UN has “consistently refused to act” on her request to “stop this horrific practice.”

“When Chinese dissidents come to the UN to speak out about human rights abuses, the last thing they expect is for the UN to report them to China,” she said.

Chinese Influence at the UN

Concerns over the Chinese regime’s influence at the United Nations Human Rights Council have been mounting in recent years.In July, the Chinese delegate twice interrupted Hong Kong singer and activist Denise Ho during her testimony at the council, during which she appealed to the UN to remove China from the organization and speak up for Hong Kong, a city embroiled in protests since June in opposition to perceived growing political interference from Beijing.

In November 2018, eight non-profit groups in a joint statement expressed concerns after the United Nations Human Rights Council removed at least seven of their submissions in a report for consideration by UN member states ahead of a review of Beijing’s human rights record. The groups voiced concern that the submissions were objected to by the Chinese Communist Party.

In April 2017, security officials at the UN headquarters in New York expelled a prominent Uyghur activist Dolkun Isa from the premise without explanation. Later in 2018, the former Under-Secretary-General for the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Wu Hongbo, revealed in an interview with Chinese state broadcaster CCTV that he had personally ordered the activist’s expulsion.

“As a Chinese diplomat, we can’t be a bit careless when it comes to issues relating to China’s national sovereignty and national interests,” Wu said at the time.

The Chinese regime has detained an estimated more than 1 million Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in the northwestern region of Xinjiang in a massive campaign to combat purported “extremism.”

Ted Piccone, senior fellow at Washington-based think tank Brookings Institution, warned that the Chinese regime is “playing the long game” in regards to human rights and reshaping the international system to its advantage.

“Without a well thought out and long-term counter-balancing strategy, China’s growing economic leverage will probably allow it to achieve its objectives”—defending its “authoritarian system of one-party control” and exporting its values that undermine international human rights system, Piccone wrote in a 2018 report.

“The result would be a weaker international human rights system in which independent voices are muffled and public criticism of egregious abuses muted behind the banner of national sovereignty.”