Canada’s Public Health Agency has not come even close to meeting its target to eliminate tuberculosis, after six years of effort.

An agency report, “Evaluation of the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Tuberculosis Activities,” published on June 22, said tuberculosis rates “have not decreased.”

“After a significant decrease and then stagnation Canada’s tuberculosis rate is increasing again,” said the report. No reason was given, according to Blacklock’s Reporter on June 28.

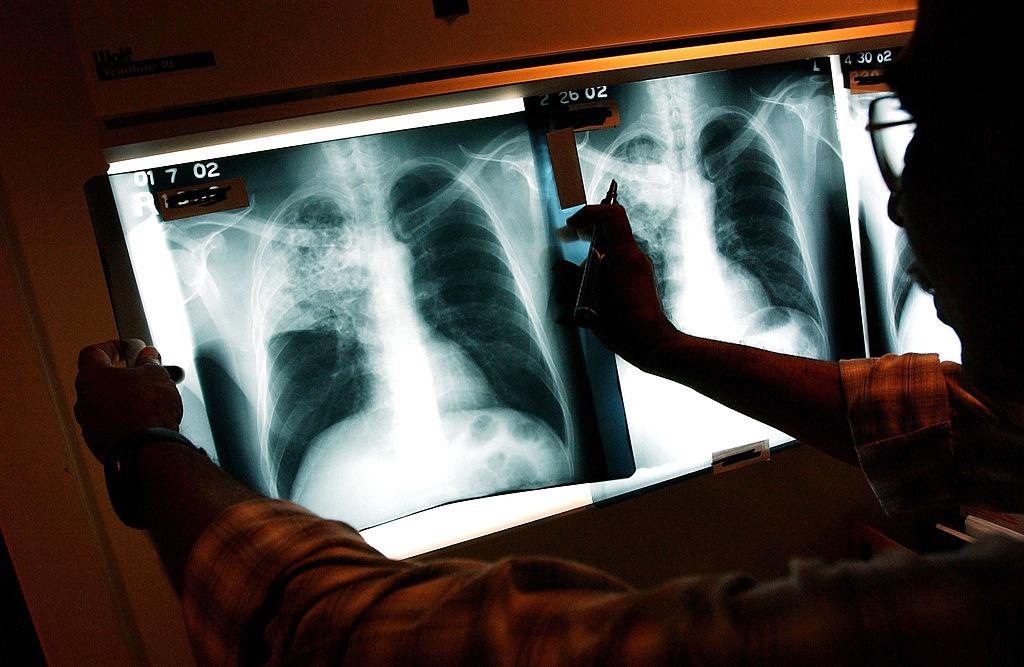

Tuberculosis (TB) is a highly infectious disease targeting the lungs and respiratory system. Canada’s rates are among the lowest in the world, but two populations are disproportionately affected: Indigenous communities in Canada and foreign-born individuals from high-incidence countries.

According to the Canadian Lung Association (CLA), TB is a “serious disease caused by breathing in bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis.” TB typically infects the lungs but can attack other parts of the body including the kidneys, spine, and brain.

TB can be spread through the air. Globally, approximately 10 million people develop the disease and about 1.5 million die from it.The Public Health Agency’s Infectious Diseases Program Branch (IDPB) has a primary objective to reduce the rate of TB in Canada, and between 2015 to 2021, had an annual budget of roughly $2.5 million a year for TB activities.

Promises to End Epidemic

In 2018, cabinet promised to “end the tuberculosis epidemic by 2030” and pledged $136.5 million in funding over a 10-year period to reduce Inuit TB rates by 50 percent by 2025. Cabinet again reaffirmed this commitment in 2021.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the time extended an apology for tuberculosis management by federal agencies in the 1940s and ‘50s. “For too long the government’s relationship with Inuit was one of double standards and of unfair, unequal treatment,” said Trudeau.

“Elimination is defined as less than one case per 100,000 people,” said the report. “After a significant decrease in the 1990s and early 2000s active tuberculosis incidence stagnated for a decade but has slightly increased since 2014.”

The report said considering the rate of TB in 2020, Canada would have to decrease infections by 10 percent per year to meet the elimination targets.

The infection rate in 2014 was 4.6 cases per 100,000 population nationwide. By 2019, the rate had increased to five cases per 100,000.

“In comparison the United States tuberculosis rate has been decreasing continuously since the early 1990s, passing below Canada’s rate in the mid-2000s,” said the report, attributing a significant part of the tuberculosis rate gap in part to differences in demographic makeup between Canada and the United States.

Canada has higher proportions of foreign-born and Indigenous populations, said the report.

Among immigrants, the tuberculosis rate is 15 cases per 100,000 people. In the Indigenous community, the rate is 19.8 per 100,000. Inuit are also affected by TB, with 194 cases per 100,000 people, which the report states is a level that has not been seen in the general population since 1908.

Tuberculosis has not been a leading cause of death in the general population since 1951. “Around 85 percent of tuberculosis cases have been successfully treated every year while seven to eight percent of active tuberculosis cases have resulted in death,” said the report.

The report also notes that Canada’s rate is increasing and may still spike, which it attributes to “limited access to care” during COVID.

“TB rates among Inuit remain almost 500 times that of the Canadian-born non-Indigenous population, while a significant proportion of cases are found among the foreign-born population,” said the report.