CHINA—According to a senior official of the Ministry of Education, the number of illiterate people in China grew by more than 30 million between 2000 and 2005, in spite of China’s efforts to eradicate illiteracy. The number of illiterate people in China was 11.3 percent of the world’s total in 2000, right after India, and 15.01 percent in 2005, or 116 million people who were illiterate at the end of 2005.

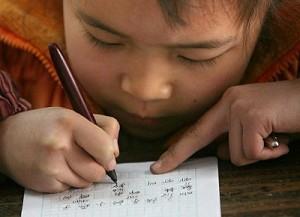

China Daily reported that China defines illiterates as those who can read and write less than 1,500 Chinese characters. Gao Xuegui, director of the Illiteracy Eradication Office of the Basic Education Department at the Ministry of Education, said, “The situation is of grave concern. Illiteracy is not only a matter of education, but it also has a great social impact.”

Gao emphasized that illiterate people in China fit into a geographic pattern. The western regions have only about 40 million illiterates, while the central and eastern areas in the more developed regions of the country account for two-thirds, with 9.63 million in Shandong Province alone.

Hu Xingdou, Professor of Economics and China Issues at Beijing Institute of Technology, said in an interview with Voice of America that the actual number of illiterate people in China is hard to estimate because local governments cover up and lie about the actual number.

China Daily reported that Guo Hongxia, a scholar from the China National Institute for Educational Research, warned that China may have difficulty meeting UNESCO’s projected target of reducing 50 percent of its illiterate population by 2015.

Gao Xuegui said that the budget for eradicating illiteracy is only 8 million yuan (US$1.03 million) per annum, which works out to 0.07 yuan (or less than 1 cent US$) for each illiterate person. It is far from enough to meet the criteria.

Beijing declared 12 years ago that it would carry out a nine-year compulsory education policy by the end of the 20th century. Six years have passed in the 21st century and the goal has not been realized.

Currently, more than 170 out of 190 countries and regions around the world have realized the need for compulsory education. In China, however, education, medication and housing have become the three big roadblocks to people’s progression.

Yang Yingfang, a former student of Enling Junior High School in Gansu Province, committed suicide because she was unable to continue her education.

Yang’s family earns 2,000 to 4,500 yuan (approximately US$241.5 to 543.5) per annum, but the living and education expenses for their two children amounted to 7,000 yuan (approximately US$845.5). In 2005, the family earned about 1,000 yuan (approximately US$120.8) and the initial payment for part of the children’s education was 1,700 yuan (approximately US$205.3). Their father was forced to make a critical decision. He held two lots in his hands, and said to his children, “The family can’t afford to pay for both of your educations. You have to draw lots to decide which one of you can attend school.”

Unfortunately, Yang Yinfang drew the “No” lot. She later cooked the family meal and did all her farm work, before throwing herself off a 300-meter cliff.

Children in China cannot afford to go to school in their own country. Many of the children in the southwestern border of China have no choice but to go to school in Vietnam and Myanmar, even though these countries are economically less developed than China.