Recently the filmmaker George Lucas of “Star Wars” fame produced two films about the Tuskegee Airmen, an all African American flying squadron that was created in 1941 at the Tuskegee Institute, a private college in Alabama.

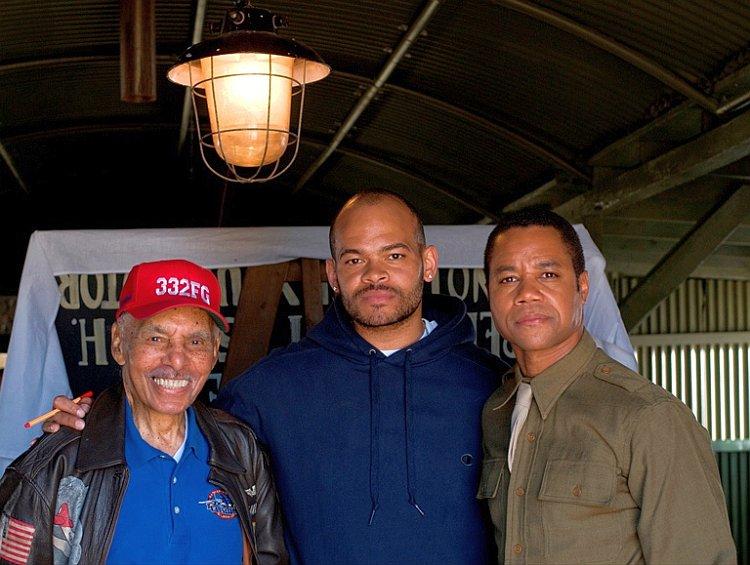

The first to be released in November of 2011 was the documentary “Double Victory.” The documentary allows the airmen to tell their stories in their own words. “Double Victory” was promoted as a companion piece to the action-adventure and historical re-enactment “Red Tails,” which opened nationwide on Jan. 20.

Before 1940, African Americans were limited to certain menial tasks within the military and had not been given an opportunity to hold leadership positions, nor were they given skilled training, such as flying. Much of that changed due to the passing of the 1940 Selective Service Training Act. In 1941, the Civil Aeronautics Authority began an experiment with an all African American flying squadron at Tuskegee Institute for the purpose of training African Americans to fly and maintain combat aircraft.

Tuskegee was a natural choice. Booker T. Washington, founder and president of Tuskegee Institute, had created an excellent program at the college. It already had a thriving civilian pilot training program under the direction of Charles Alfred Anderson, the nation’s first African American to earn a pilot’s license. It also had the facilities, engineering and technical instructors, and the climate necessary for training pilots year-round. However, once the program was installed, it received very little support from the U.S. military.

As depicted in the documentary and confirmed in a telephone conversation with Tuskegee Airman Hillard Pouncy, the training camp for the airmen was bare and basic. Housing consisted mostly of tents. Running water and heat was limited, and there were no special amenities in the camp. The sleeping quarters were tight to say the least.

Training took up most of the men’s time. Mr. Pouncy believes the conditions under which the airmen trained and lived made far stronger, more tolerant men who were ready to fight for their country when given the opportunity.

Eventually the program caught the eye of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who was very interested in the work at Tuskegee Institute, particularly in the aeronautical school. In 1941, Mrs. Roosevelt paid a visit to the Tuskegee Army Air Field. While there, she asked to take a flight with one of the pilots.

Flight instructor Charles A. Anderson piloted Mrs. Roosevelt over the skies of Alabama for over an hour. That flight proved for Mrs. Roosevelt that blacks could fly airplanes, and she did everything in her power to help them in that endeavor.

Mrs. Roosevelt continued her support of the Tuskegee Airmen program and kept in touch with Tuskegee President F. D. Patterson often. In March of 1942, the first class of African American aviation cadets earned their silver wings to become the nation’s first black military pilots.

From 1941 to 1946, over 2,000 African Americans completed training at the Tuskegee Institute, nearly three-quarters of them qualified as pilots. The rest went on to become navigators or support personnel. Together they were known as the Tuskegee Airmen. They later became known as “Red Tails” or “Red Tail Angels” because the tails of their P-51 Mustang planes were painted red.

Roughly over 1,000 black aviators were trained at Tuskegee, and 450 would later take part in the war effort.

In “Double Victory,” the airmen spoke often about staying focused on the task at hand, which was training to become pilots. Things like discrimination and segregation were of little interest as the airmen were kept busy training. Mostly, it was about completing training with pride and dignity.

At a screening reception for “Double Victory” held at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem this past November, Tuskegee Airman Roscoe Brown said, “We were the best pilots and we would let everybody know we’re the best pilots, and the segregation that we faced just inspired us to do better.”

The airmen’s mission lasted two years from 1943 to 1945. Their role, which proved extraordinarily significant, was an escort mission, helping bomber planes to reach their targets and return home safely. It required significant commitment and sacrifice, and they are celebrated for having never allowed a bomber in their protection to be shot down.

Several individual pilots earned Silver Stars or Purple Hearts. In addition to shooting down enemy attack aircraft, they also shot down the belief that African Americans were not suited to responsible military service duty. In 1948, President Harry Truman issued an Executive Order desegregating the U.S. military.