NEW YORK—Summer break. There is nothing not to like about it. Maybe it’s the ingrained feeling of beach sand under your feet, or the smell of pine trees deeply rooted in summer camp memories. It just gets under your skin, much like the beefy smell of thousands of hamburgers grilled during high school summer jobs.

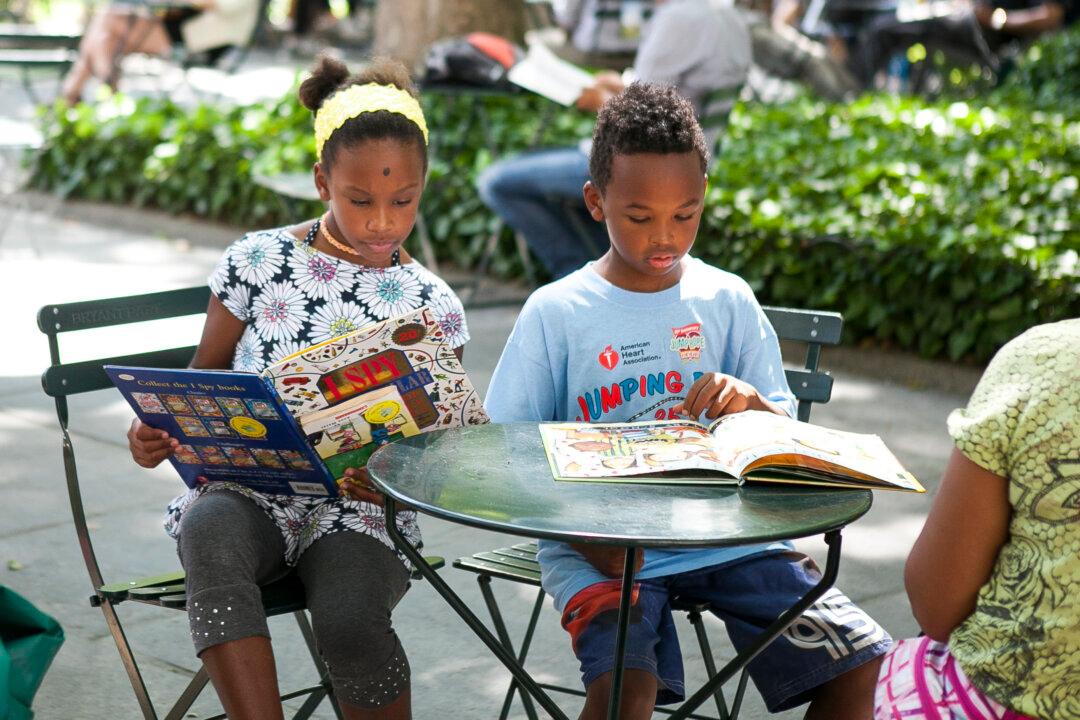

Browsing through the memories, it’s almost unimaginable that for over 2 million American children, summer break is an obsolete concept.

Nearly 4,000 schools across the nation operate on a year-round schedule—and for good reasons.

Duke University education professor Harris Cooper published a research summary in 2003 that found children regress by the equivalent of about one month of instruction over the summer. The loss was over two months for math, and more pronounced for low-income students in reading.

The concept of summer “brain drain” was coined and both schools and parents started to pay more attention. “Within the culture, there is an increasing awareness and an increasing sense of ’something needs to be done,'” said Alberto Bursztyn, Brooklyn College professor of school psychology and special education.

Students get packets with required reading and math practice to do over the break and the number of math camps has also increased, according to Maggie Feurtado, a seventh grade math teacher at the elite Lab School for Collaborative Studies in Chelsea.

But Bursztyn argues the break harms more that just the students’ loss of knowledge. The school environment is such a major part of children’s lives; it plays a key role in their social and cognitive development, and adults should consider “how the black hole of two months could set that back,” Bursztyn said. That’s why children with disabilities in New York City receive schooling all year round, as an interruption could cause them to regress.

Entrenched

Yet changing an institution as fixed as summer break can bring about resistance.

“Summer break has existed, historically, to satisfy the needs of the adult world, not necessarily children,” Bursztyn said. “Changing the schedule, no matter what, is likely to bring about a great deal of reaction from all the entities that have a vested interest in maintaining the schedule as is.”

Deena Hellmann, program director at the Goddard Riverside Community Center, a summer programs provider, is even more direct. “It’s a negotiated item with the union,” she said. Any change that would require teachers to put in additional time is a sensitive issue with the teachers’ unions.

“But from my developmental perspective, if we’re looking at what children need, it would be advisable to have some way of thinking of schooling as a 12-month project,” Bursztyn said. “There should be something available that promotes learning, perhaps in a different way.”

There are many summer activities for children, even in the concrete jungle of New York City. But they’re seldom free. Many families find the options unaffordable. “For some unfortunate kids with parents, low-income parents with less means, many kids are just sitting home,” Hellmann said.

“They really don’t have much to do,” said Sean Ahern, a high school teacher at East River Academy. He’s had his share of experience with troubled teens, as his school serves the youth incarcerated on Riker’s Island.

As with many issues, a lack of deep pockets can be made up for with more knowledge and grit. “Parents who are better informed, better educated themselves, will be more on top of this concern,” Bursztyn said. And where awareness and access is limited, children “suffer the consequences.”

Systemic Change

About 2 million students across the nation attend schools with a year-round schedule. That doesn’t necessarily mean a longer school year. Usually, it’s just the matter of replacing the summer break with several two-week breaks, or two month-long breaks throughout the year.

Almost half of such students with year-round schedules are in California, where the concept was introduced in the 1980s to alleviate school overcrowding. It never took off in New York though, where only 21 such schools existed in 2007, 16 of them charter or private.

In 2004 the Citizens Budget Commission calculated that switching to a year-round schedule would create almost 400,000 school seats. Even if spaces were preserved for summer programs, some 170,000 new seats would remain.

The problem is the year-round schedule can be annoying, even disruptive. To achieve the effect of saving space, students “take shifts” going to school. One group is always on a break.

How can a family schedule a vacation if their children happen to have breaks at different times? How can older students get a summer job if they only get a few weeks off every couple of months? How can all students participate in a school-wide sports tournament, if they go to school in shifts? And when would the principal take a break?

Bursztyn would “advise to continue experimenting along those lines.” And Ahern agrees. “The answer is not to keep them locked up in schools,” he said, but to let them “enjoy themselves and continue to learn but in different settings.”

Additional reporting by Jonathan Zhou