There is an ancient culture that flourished in Mesoamerica around 1100 A.D. still baffling historians—the mysterious Olmecs. Their religious rituals are far from completely understood, but so too are their origins. How did this culture that appeared seemingly overnight go on to exhibit such an enormous influence on the rest of the region?

According to several authors, including Mike Xu, professor of Chinese studies at the University of Central Oklahoma, the Olmecs are descendants of ancient Chinese. The evidence? The Olmec culture began around 1100 A.D., some years after the fall of China’s Shang dynasty (1766 to 1122 B.C.).

According to ancient chronicles of that era, when the Zhou were invading and plundering the Shang, records state that the son of the emperor brought 25,000 adepts toward the “eastern ocean.” According to Mike Xu, these were the first Olmec people.

At that time in history, China’s ocean fleet was the most advanced of the day. Some historians propose that these Chinese travelers could have arrived on the American coast thanks to the “black current.” Known as Kuro Shiwo or “current of death” in Japanese, this Pacific current would have been capable of navigating an ancient Chinese sailor to the Americas.

In his article for the sailing magazine 48 Degrees North,“Are We Living in the Land of Fusang?” Hewitt R. Jackson writes that there is evidence of similar pre-Columbian Chinese sea voyages that have already been confirmed:

“Probably the best documented account that has been studied is that of Hwui Chan (Hoei Shin). He was a ”cha-men“ or mendicant priest who had made his way from Afghanistan among the first of the Buddhist missionaries to reach China. This was a period of great expansion for Buddhism and extraordinary journeys by land and sea were common for the ”cha-men.”

Hwui Chan sailed to the Americas some five hundred years before Leif Erickson and a thousand before Columbus. His description of the land he visited seems to indicate that he passed by California and settled in Mexico. After a stay of forty years he returned to China in 499 A.D. and related the story of his labors and travels to Wu Ti, the Emperor.

The story of Fusang was at that time well known in China. This eventually has been recognized and accepted by western scholars, but for some reason it has fallen out of fashion in our history and literature within the past century.”

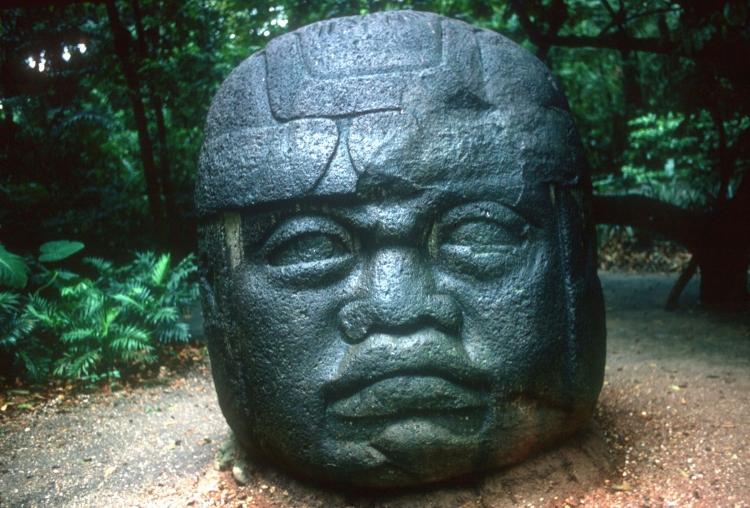

While the black current explains the journey, ancient Olmec artifacts give the theory further substance. The written language found on the Olmecs’ jars, pottery, and statues reveals what could be the actual influence of Chinese culture.

Professor Xu points out that various words found on these decorative objects match exactly with those used in Shang China: Sun, Mountain, Artist, Water, Rain, Sacrifice, Health, Plants, Wealth, and Earth. In fact, the majority of the 146 characters used by the Olmecs are exactly the same as primitive Chinese writing. When Xu showed the Olmec artifacts to university students involved in analyzing primitive Chinese culture, they actually believed it was ancient Chinese script.

While most Mesoamerican scholars do not accept Xu’s theory—critics have labeled him “the most dangerous person in Mesoamerican research”—it nevertheless offers insights about the mysterious Olmecs that more accepted theories cannot reach.

In her letter to Science magazine in 2005, Betty J. Meggers of the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution criticizes most Mesoamerican scholars’ failure to acknowledge Xu’s comparisons:

“The invention of writing revolutionized Chinese society by facilitating communication among speakers of 60 mutually unintelligible languages and resulted in increased commercial interaction and social integration. The rapid diffusion of Olmec iconography and associated cultural elaboration suggests it had the same impact across multilingual Mesoamerica. The demise of the Shang Empire circa 1500 B.C.E. coincides with the emergence of Olmec civilization. Rather than speculate in a vacuum on the intangible character of Olmec society, it would seem profitable to compare the archaeological remains with the detailed record of the impact of writing on the development of Chinese civilization. What do we have to lose?”