A series of internal government reports have revealed in greater detail how Chinese authorities censor and suppress negative news stories, especially incidents that could draw scrutiny of officials.

According to the Chinese regime’s own estimates, as of 2019 there were more than 850 million internet users in China. Since the advent of the internet, the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has placed enormous resources into controlling information and manipulating public opinion to its interests.

Suppressing Negative News Stories

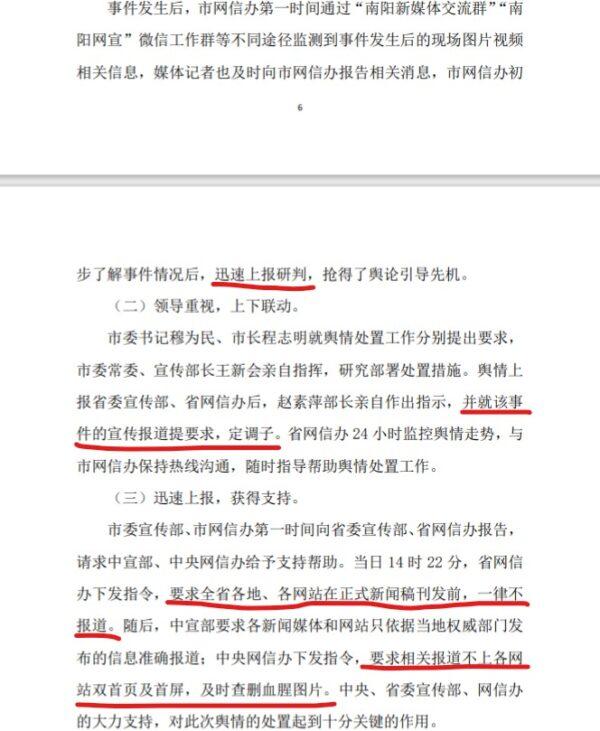

In the Zhumadian city’s annual yearbook on “internet work,” authorities detailed how they spread false information to manipulate public opinion.In 2016, the Nanyang city’s local branch of the Cyberspace Affairs Office suppressed photos of a fatal car accident that caused multiple casualties and put out different narratives trying to minimize its “negative” impact, according to the documents.

According to Chinese media reports, on February 29, 2016, at an intersection in front of the city’s First Middle School, a white SUV suddenly sped up and drove into a group of students, killing 1 and injuring 11. The driver was a retired bureau chief at the Nanyang prosecutor’s office. After retirement, he worked for a local real estate company. After the company accumulated enormous debt and the business owner ran away, the man was chased by creditors. He intentionally drove into a crowd in order to take revenge on society, according to media reports.

Local authorities soon took measures to control public opinion about the incident. First, the local Cyberspace Affairs Office “reported promptly to higher authorities for research and assessment,” then the Propaganda Department of the provincial Party committee “put out requirements and set the tone” for reporting of the incident. Local media and news outlets were not allowed to report about the incident before the official version was to be released by the government. Authorities also ordered media outlets to take down all photos and videos of the incident from their websites.

Authorities admitted that their intervention “caused more attention and negative public opinion regarding the incident and panic in society.”

This similarly happened with a police shooting of an unarmed man that occurred on May 2, 2017. A black sedan was blocked by police at a highway exit in Sanmenxia city. When the driver tried to turn around and drive away, several police officers opened fire and killed the driver inside.

Several videos of the shooting circulated online and attracted public attention.

The document stated that the city’s police and Cyberspace Administration (a censorship agency) soon made public statements to “guide the development of public opinion.” It also drafted a directive to the city’s hired internet trolls—commonly known as the 50 cent army—instructing them to make positive comments. The official social media accounts of city police would also “like” those posts. If there are negative comments, the trolls should “conduct interactive guidance”—meaning they should respond to the posts with positive comments about the local government.

Shifting Attention Away

Another tactic is to shift the public’s focus away from a negative incident by creating a new “hot topic.”The document explained how the tactic worked in a local case of telecommunications and phone fraud. On Sept. 26, 2016, mainland Chinese media reported that 113 villagers in Shangcai county of Zhumadian city were wanted by police for pretending to be military personnel to commit telecommunication fraud. It attracted great public attention online.

After the fraud case was exposed, “in order to reverse this situation,” the city’s Cyberspace Administration decided to hold an online publicity/PR event, “to publicize and guide online public opinion”—in other words, to divert public attention from the fraud case.

Authorities decided to hype up an upcoming cultural festival instead. A team of the city and county’s hired online trolls wrote a large number of articles related to the event and set up topics in relevant online forums. They also posted comments and shared articles more than 1,000 times within 48 hours, according to the document. In the end, the government concluded that with this new hot topic, it successfully turned public attention away from the fraud case.

‘Unified’ Propaganda

The document also showed that local and central government authorities often coordinate to ensure that their propaganda narratives sync up.For example, on Sept. 22, 2016 in Sui county, a kindergarten school bus crashed with a big truck, causing multiple casualties. State media outlets gave two different numbers of casualties. Henan Business Daily and Dahe Daily reported 6 dead and 28 injured with photos from the scene; while Xinhua reported only 13 injured, including 2 in critical condition. Soon, Dahe Daily’s report was deleted. The document recorded that after the incident, the Shangqiu city Cyberspace Administration interrogated and scolded several officials who managed the government social media accounts, as they posted and shared “false information.”

The Cyberspace Administration also interrogated the leaders of Henan Business Daily and Dahe Daily, and ordered them to “reform” immediately and hold relevant personnel accountable for the discrepancy in reported casualties.