Commentary

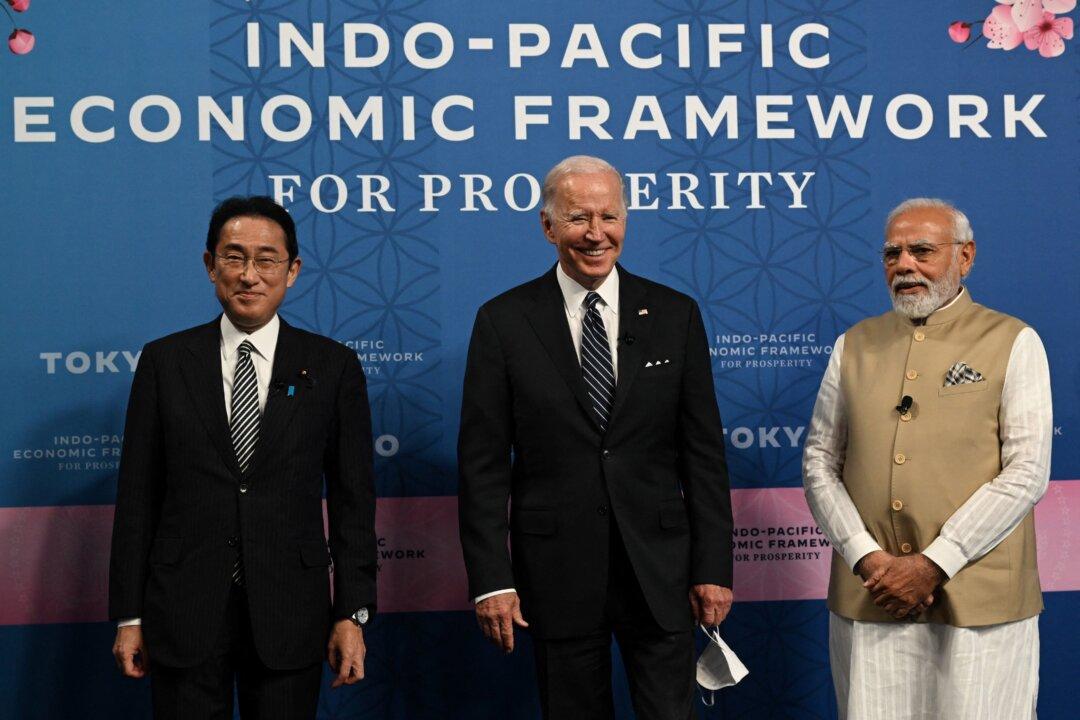

President Joe Biden took advantage of his first Asia trip to announce a so-called Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). He floated the idea to an assembly of 12 nations from the region, notably not including China and Taiwan.

President Joe Biden took advantage of his first Asia trip to announce a so-called Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). He floated the idea to an assembly of 12 nations from the region, notably not including China and Taiwan.