River blindness afflicts around 25 million people around the world, mostly in Africa and South America. The disease can be treated with the ivermectin drug (IVM), but many of those infected never undergo treatment.

The problem with IVM is that it can have fatal side effects for those who are also infected with Loa loa, an African eye worm that, contrary to its name, doesn’t cause blindness.

The standard procedure for the treatment of river blindness in many places of Africa involves a lab manually counting the worms in a blood sample to determine whether the patient has Loa loa. Now, researchers at the University of California–Berkeley have found an easier way to do the screening—with a smartphone.

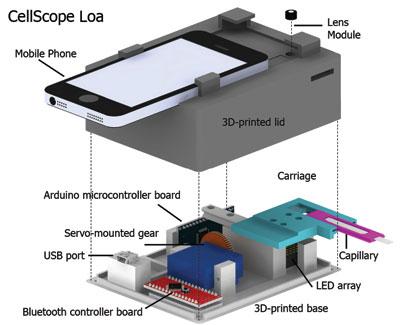

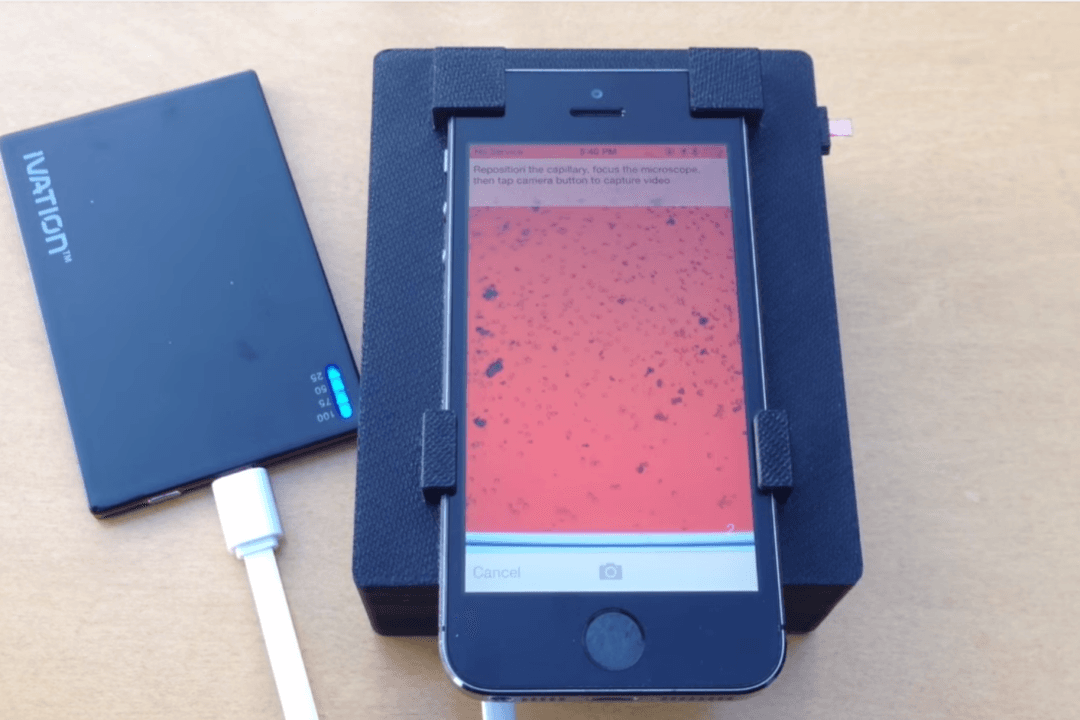

The researchers wrote a software app that can analyze the blood sample with one click and created a mounting platform for the smartphone—the platform is simple enough to be produced with a 3-D printer—which together make up the CellScope Loa.

“We previously showed that mobile phones can be used for microscopy, but this is the first device that combines the imaging technology with hardware and software automation to create a complete diagnostic solution,” said Daniel Fletcher, a professor of bioengineering at UC Berkeley, in a statement.

The platform is controlled by the smartphone via Bluetooth. After inserting the blood sample in the deposit, the user clicks on the smartphone to start the analysis, and the gears automatically slide in the sample to be viewed by the microscope.